This post is going to be a bit different from my usual. I’m going to be discussing a certain kind of adaptation, which I’ll call “the adaptation as commentary,” its advantages and disadvantages. As examples, I’ll be using two movies I’ve written about in the past. Hopefully, it’s been long enough that my regular readers won’t groan and say, “not this again!” While there will be some overlap with my past discussions, I will be looking at the films from a different angle. That also means I’ll be a lot freer with spoilers and my past blog posts about these movies were already pretty spoiler heavy, so if you don’t want a first-time viewing experience ruined, I advise you to skip this post.

There are many things that I want from an adaptation of a book I love, one of them is that it serves as an introduction for newcomers to the story, even though I’m not a newcomer myself. I love that I can watch the BBC’s 1999 David Copperfield, which I recently recommended, with my friends who would never read the book and be confident that afterwards they’ll understand exactly why I love it. They won’t know every reason why, mind you. But they’ll get the gist. Remember I wrote that the adaptation should be an introduction to the source material, not a complete reproduction.

But there are some adaptations that are less introductions and more commentaries on their source. Of course, you could argue that every adaptation is a commentary on some level. What the adapter chooses to leave, cut, expand on and downplay indicates what they consider the best or most important parts of the original and often tells us as much about them as about the source. But it’s considerably truer of some adaptations than others. These “commentaries” can sometimes, though not always, be very intelligent and thoughtful and are what some fans want from adaptations, but they come with distinct tradeoffs. In this post, I’ll be examining two modern(ish) movie adaptations of classic and oft-adapted works of children’s literature, the 2003 Peter Pan and the 2019 Little Women. I included both of these in my list of top five screenplay adaptations albeit only for adaptations this blog covered in its first year. I’d even argue that they’re truer to their source materials in some ways than past takes on them.[1]Peter Pan is more upfront about the violent nature of Neverland than either the classic Disney movie or the thrice filmed stage musical and Little Women is the only movie version to really give the … Continue reading I didn’t choose them to discuss because I think they’re examples of the adaptation-as-commentary done wrong. However, I’m going to argue that neither works well as an introduction to the original books.

Taking its cue from the 1953 animated movie, the 2003 Peter Pan has young Wendy Darling fly away with Peter on what her father had intended to be her last night sleeping in the nursery with her younger brothers. Thus, her flight becomes a deliberate avoidance of maturity, something latent in the original novel and stage play by J. M. Barrie, but less overt. This Peter Pan doesn’t just lure Wendy away with promises of seeing mermaids and pirates and of having all the lost boys respect her. What ultimately convinces Wendy to turn her back on her loving parents is his invitation to “never have to worry about grownup things again.”

Barrie’s attitude toward growing up in Peter Pan is hard to pin down. Like Peter, he seems to get bored and switch sides when winning a fight too easily. In the book’s last chapter, he dismisses the lost boys as “goats” for having left the island to be adopted by Wendy’s family and grow up. But he also treats Wendy’s growth positively or at least neutrally, saying that “she was one of the kind that likes to grow up. In the end she grew up of her own free will a day quicker than other girls.” Then again, the adult Wendy does regret her decision when Peter comes to take her back to Neverland and she can’t go. Barrie is very upfront about the wonders of Neverland that adults can’t enjoy, but he’s also very upfront about the consciences that adults have and children, in his estimation anyway, do not. Of course, consciences aren’t necessarily fun things to have and for some (evil) people that may be an argument in favor of eternal youth. Barrie’s Peter Pan leaves readers and audiences to come to their own conclusions. Director and screenwriter P. J. Hogan however overtly makes the case against running from adulthood. His Wendy decides to return home when she realizes to her horror that she and her brothers are forgetting about their parents. What prompted Barrie’s Wendy to do this was the idea that her parents might be forgetting her, which was arguably just more childish selfishness.[2]Though the book does describe Wendy as being disturbed by the way her brothers’ memories of home and her own were fading, but not enough to make her leave Neverland.

Something that this movie wants adult viewers to keep in mind, which the Disney movie didn’t, is the reason growing up entails Wendy no longer sharing a room with her brothers: her budding sexuality. This was always implicit in the book and the play with her crush on Peter, but the movie makes it a main theme. In the second scene, more or less, Wendy’s busybody aunt declares that she’s almost a woman and needs to start thinking about marriage. As evidence of this, she says that Wendy has a kiss hidden in the righthand corner of her mouth.[3]This language comes from the book but as is typical of the movie, its context is different. This, she tells her uncomfortable niece, is for the greatest adventure of all. In a wink-wink nudge-nudge moment aimed over the heads of young viewers, Wendy’s schoolteacher is scandalized to find that Wendy has drawn a picture, inspired by her first glimpse of Peter, which tellingly went to her mother in the original story, of a strange boy in her bedroom watching her sleep.[4]Peter’s costume also shows a great deal of skin and occasionally so do those of the lost boys. This is sort of eyebrow raising given rumors of child predators in the entertainment industry, but … Continue reading

Ironically, Wendy’s puberty is as much what draws her to Peter as it is what scares her away from her family. But though he enjoys playing father to the lost boys with her as the mother, he can’t or won’t return her feelings. At one point, he asks her for assurance that their roles are “only make believe” and when she gives it to him, he’s relieved since “it would make me so old to be a real father.” This bothers Wendy who then tries to Define the Relationship, asking Peter what his “exact feelings” are for her. All this comes from Barrie[5]Though significantly, in his version, it follows Peter and Wendy acting out a domestic scene, sitting by the fire and talking about their children whereas, in the movie, it follows a scene of them … Continue reading, but what follows is much more dramatic. In the book and the play, Peter casually replies that his feelings are “those of a devoted son.” Wendy stomps off in a huff and when Peter, more curious than exasperated, asks what it is she wants to be to him that’s not a mother, she primly says, “it isn’t for a lady to tell.” With that, the issue is dropped. In the movie, Wendy explicitly brings up the concept of love and Peter responds negatively, saying that the very sound of it offends him. His response is even more negative when Wendy argues that there’s much more to life than flying and fighting and that it becomes clearer when you grow up. Later, when Peter insists that he wants to always be a little boy and have fun, she replies, “you say so, but I think it is your biggest pretend.” Surprisingly, to me anyway, this line comes from Barrie’s stage directions for the play. However, there it was only for the director and the cast to know. The movie explicitly makes the case that refusing to grow up is a waste, resulting from cowardice.

Wendy’s not the only character to call Peter out here. The adaptation’s climax is much more emotional than the one in the original, which was a basically a lark.[6]I should note that it starts out as lark and this movie captures much more of the book’s fun than Disney’s recent, Peter Pan and Wendy, which gave the latter character an arc similar to … Continue reading Here Captain Hook taunts Peter with the knowledge that Wendy was about to leave him before she was captured.[7]It’s a pity I couldn’t give Jason Issacs’s Hook a mention in my “awards ceremony” or any of the other great portrayals of the character from other versions of Peter Pan. … Continue reading He calls Peter “a tragedy” on the grounds that he’ll never live up to his potential and be able to give Wendy what she really wants. “You die alone and unloved,” he says, “just like me.” Here the character of Hook acts as a commentator, drawing parallels between himself and his adversary. (Along similar lines, he tells Tinkerbell, a character who is obsessed with Peter in a way different from his, that by killing him, they’ll both be free.) Only when Wendy gives Peter her “hidden kiss”, demonstrating that she really does love him even if he can never be her husband, is he able to defeat Hook.

The 2019 Little Women makes far fewer changes to its source material’s story and characters than the 2003 Peter Pan does. But in some ways, the adaptation’s function as a commentary on the original becomes even more obtrusive. This is because, for better and for worse, it ends up being just as much a movie about the book, Little Women, as it is a movie version of Little Women, but we’ll get to that later.

The main way director/screenwriter Greta Gerwig comments on the original novel by Lousia May Alcott is by drawing contrasts between its first half and its second half through her movie’s nonlinear story. It begins with the March sisters as adults, having gone their separate ways for the first time. Meg is raising two children with her husband, Jo is in New York working as a governess and part time writer, Amy is in Europe studying art and Beth is still at home with her parents. All this is intercut with flashbacks of them seven years ago when they were all together. (Both the past and present storylines proceed chronologically.)[8]The 2019 movie is technically not the only adaptation to use this device. The 2018 film, which sets the story in modern times, does it too, though with less of a purpose behind it. I can’t … Continue reading While the sisters always had different personalities and goals, the emphasis in the flashbacks is on them as a unit and on the cheerful camaraderie they had between them that they miss in their adult lives. What’s also stressed is how much more confident they were in their youth about achieving their dreams. Thus, we cut from Meg happily partying with her rich friends in the past to her worrying about money with her husband in the present.[9]Though even in the flashbacks, Meg, being older, was more realistic about her dreams’ plausibility than Jo and Amy were. Visually, the scenes set in the past and the present also contrast each other with the former being all bright, warm, nostalgic colors and the latter grayer and grittier looking. This suggests the flashbacks are colored by nostalgia. We’re not seeing so much what really happened back then as what Jo remembers.[10]I’m not sure how this can be the case when some of those scenes are from the perspective of her sisters, mother and neighbors. Maybe they’re supposed to be the family’s collective … Continue reading The movie doesn’t cut any of the bad things that happen during the childhood section of the story and neither does it cut any of the good things that happen in the adulthood section, but it consistently deemphasizes them.

The most striking contrast created by intercutting is between Beth’s two bouts with Scarlet Fever. After a montage of her family taking care of her in both the past and the present[11]The nonlinear storytelling really benefits the movie’s pacing here as two such montages would be repetitive and skimping on one would make the outcome of each obvious., we see a flashback of Jo waking up to find Beth’s bed empty. She rushes downstairs in a panic to find her not dead but sitting up and eating, well on the road to recovery. Then we get the uplifting scene of the girls’ father, who has been at war and dangerously ill himself, returning home for Christmas. And then Jo wakes up in the present to find Beth’s bed empty. Slowly, she comes downstairs to find that this time Beth really is dead. Then we get the sad scene of her funeral. This is one case where the contrast explicitly isn’t the result of Jo’s nostalgia, but ironically Beth’s initial recovery was something of a wish fulfillment fantasy on Louisa May Alcott’s part. She based Jo’s personality on herself and Beth’s on that of her sister, Elizabeth, who had died before she wrote Little Women. The first half of the book, ending with the father’s return and Meg’s engagement, was originally the whole thing. When Alcott wrote about Beth’s illness, she was probably depicting how she wished it happened for her sister and when she wrote the sequel, which is now considered part of the book, she was writing something closer to what had actually happened though still probably a somewhat idealized and sanitized version.

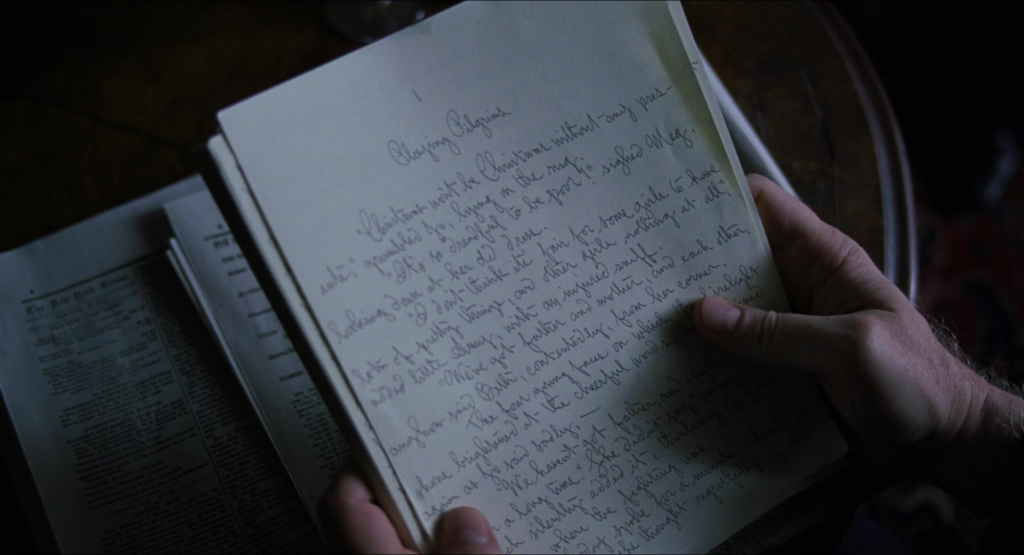

Instead of writing a short story inspired by her memories of Beth, as in the book, the movie’s Jo expands on a short story she wrote for her about their childhood together, turning it into, well, Little Women or the first half of it anyway. This isn’t the only movie adaptation to make that change, but it’s the one that does it in the most interesting way. Jo sends the first twelve chapters to Mr. Dashwood, her editor in New York, telling him in a letter that “it could suit as a story for young people, but I think it is probably quite boring.” Privately, with a true author’s angst, she laments to her sisters that the book can never be really great because it’s a just “a story of domestic struggles and joys. It doesn’t have any real importance.” Amy argues that people don’t realize how important domestic struggles and joys are because people don’t write books about them, and that Jo’s will be the one to demonstrate it. Here Greta Gerwig makes the case in her adaptation for the literary Little Women being great literature.[12]More cynically, you could say it’s Gerwig patting herself on the back for making the kind of movies she does while pretending to celebrate Louisa May Alcott, but it’s a great scene so … Continue reading Mr. Dashwood initially rejects the manuscript but when his young daughters get their hands on it, devour it and demand more, he changes his mind.

All this is based on the real story of Little Women‘s publication, though the facts are somewhat sensationalized. Little Women wasn’t really a labor of love for Louisa Alcott. It was an assignment and one she didn’t initially like. Publisher Thomas Niles asked her to write a story for and about young girls. She preferred boys and put the task off until she really needed the money.[13]Remember my earlier footnote where I mentioned that I tire of all the critics and fans complaining about Disney’s recent and seeming endless stream of remakes? Well, I think the story of Little … Continue reading When she did write it, she used the girls she’d known best, herself and her sisters in their childhood, as the basis for her heroines’ personalities. Niles wasn’t impressed with the first twelve chapters she sent him, but he showed it to members of the target audience who loved it, especially his niece. Encouraged by her mother and sisters, Alcott warmed to her task, realizing that “lively simple books are very much needed for girls.” She would always resent though being famous for her moralizing children’s literature rather than serious adult writing.

She also resented that her publishers and readers insisted that she end the book with all her heroines, in the words of the 2019 movie, “married or dead.” This especially annoyed her when it came to the character of Jo whom she’d modeled on her contentedly single self. The film actually works this frustration into its commentary.[14]Along similar lines, both Jo and Amy lament that seemingly the only respectable way they can make money is to marry into it. This is the most boring part of the movie’s commentary since every … Continue reading Just before the romantic finale between Jo and Professor Bhaer, we cut, for the first time in the film, from the present to the future when Jo and Mr. Dashwood are discussing the ending to her book. He objects to her intention that the main heroine not marry either of her possible love interests.[15]The main difference between this and reality is that Alcott probably wouldn’t have created Bhaer at all unless she had to give Jo a husband. “She says the whole book she doesn’t want to get married,” Jo argues. “Who cares?” says Dashwood. “Girls want to read about women being married, not consistent.” If she doesn’t relent, according to him, nobody will buy the book. Reluctantly, Jo agrees and only then do we get the scene of her and Bhaer under the umbrella, implying that it’s fictional. Dashwood finds it very moving and since he represents the pulpy commercial writing Jo is supposed to avoid, this amounts to a critique of the book’s ending, though Jo herself seems pleased that he likes it.

However, if the movie’s goal was to make the case that Jo getting married was arbitrary and out of character, it chooses a strange way to do it. Clearly, there’s more going on here. Rather than emphasizing Jo’s happiness with her liberty, her loneliness and weariness of being the only single person left in her family are depicted more dramatically than in any previous adaptation or even the book. At one point, according to the official screenplay, we’re supposed to fear that Jo will jump into a river, something Alcott really contemplated at her most despondent, though I don’t think it really registers that way on film. It’s impossible not to interpret the umbrella scene as not only a concession to marketability but as Jo’s fantasy of what she wishes had happened with the implied suggestion that Alcott was also indulging in wish fulfillment when she wrote her version. Since Bhaer is present for the final scene, taken from the book, of the Marches celebrating their matriarch’s birthday at the new school Jo has opened, that is apparently fictional too. Intercut with it is the publication of Jo’s book, which is unambiguously real. The only happy ending of which we can be sure in this Little Women, for Jo anyway, is the existence of the book, Little Women, itself.

All this is great fun to analyze but I would not want either of these movies to be anyone’s introduction to the originals. Not that I think newcomers wouldn’t enjoy them. Far from it.[16]Well, I do know that many casual viewers find it a pain to keep track of which scenes in the 2019 Little Women are flashbacks. It might not have hurt it to sacrifice a little subtlety and include … Continue reading My concern is that having watched these adaptations with all their commentary, they’ll find the book versions anticlimactic and lacking depth by comparison. Well, you might say, isn’t that because they are? I’d argue not. The impression of added depth is an illusion. While the 2003 Peter Pan may explore one interpretation of him and his eternal childhood more fully than the book or the play did, it does so at the cost of every other possible interpretation latent in the text. And the 2019 Little Women, by making it so much about nostalgia, gives the sad scenes, which are presented as real, a power it denies the happy ones, which are presented as imaginary. In the book, on the other hand, both the high points and the low points are equally valid or at least the decision is left up to the reader. Earlier in this post, I mentioned the 1999 David Copperfield.[17]That seems like a good point of comparison since, like Little Women, David Copperfield is a very personal novel about the relatable life experiences of a young author. (Both even had movie … Continue reading That adaptation may not be anywhere near as creative and interesting as the two I’ve examined here, much more of a cut and paste job[18]Though I’d argue it has a few inspired, original moments, such as Betsey Trotwood’s response to Micawber’s claim that he’s not going to make a big speech. And the book is so … Continue reading, but, unlike them, it won’t hinder viewers who haven’t read the source material from choosing their own interpretation of it.

Does this mean I dislike the 2003 Peter Pan and the 2019 Little Women? No. I probably wouldn’t recommend them as introductions to the originals, but I would recommend them to openminded and curious fans of the originals, those who don’t mind an interpretation that might not exactly align with their own. I wouldn’t agree that these stories have gained rather than lost through these adaptations-as-commentaries, but I would say they have both gained and lost.

References

| ↑1 | Peter Pan is more upfront about the violent nature of Neverland than either the classic Disney movie or the thrice filmed stage musical and Little Women is the only movie version to really give the characters of Meg and Amy their due. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Though the book does describe Wendy as being disturbed by the way her brothers’ memories of home and her own were fading, but not enough to make her leave Neverland. |

| ↑3 | This language comes from the book but as is typical of the movie, its context is different. |

| ↑4 | Peter’s costume also shows a great deal of skin and occasionally so do those of the lost boys. This is sort of eyebrow raising given rumors of child predators in the entertainment industry, but honestly it does strike me as more how adventurous boys, cut off from civilization and adult ideas of propriety, would choose to dress. I don’t think such boys would gravitate toward the tights of the traditional Peter Pan costume. |

| ↑5 | Though significantly, in his version, it follows Peter and Wendy acting out a domestic scene, sitting by the fire and talking about their children whereas, in the movie, it follows a scene of them dancing romantically together. |

| ↑6 | I should note that it starts out as lark and this movie captures much more of the book’s fun than Disney’s recent, Peter Pan and Wendy, which gave the latter character an arc similar to that of her 2003 counterpart, and which I found rather dull and joyless. I should also note though that Peter Pan and Wendy does have some fun moments and isn’t the worst movie ever or anything. I’m somewhat sick of all the YouTube videos my feed recommends decrying every new Disney remake or reimagining as a travesty. Not saying they’re all great but, come on, they’re not all that terrible either! |

| ↑7 | It’s a pity I couldn’t give Jason Issacs’s Hook a mention in my “awards ceremony” or any of the other great portrayals of the character from other versions of Peter Pan. But there was a lot of competition for great villains and Hook is a hard one to categorize being something of an affectionate parody of a villain. |

| ↑8 | The 2019 movie is technically not the only adaptation to use this device. The 2018 film, which sets the story in modern times, does it too, though with less of a purpose behind it. I can’t resist mentioning that, on the whole, I actually enjoy watching the 2018 Little Women more than this one, though I know that’s not a popular opinion. |

| ↑9 | Though even in the flashbacks, Meg, being older, was more realistic about her dreams’ plausibility than Jo and Amy were. |

| ↑10 | I’m not sure how this can be the case when some of those scenes are from the perspective of her sisters, mother and neighbors. Maybe they’re supposed to be the family’s collective memories. |

| ↑11 | The nonlinear storytelling really benefits the movie’s pacing here as two such montages would be repetitive and skimping on one would make the outcome of each obvious. |

| ↑12 | More cynically, you could say it’s Gerwig patting herself on the back for making the kind of movies she does while pretending to celebrate Louisa May Alcott, but it’s a great scene so let’s not be cynical, OK? |

| ↑13 | Remember my earlier footnote where I mentioned that I tire of all the critics and fans complaining about Disney’s recent and seeming endless stream of remakes? Well, I think the story of Little Women proves that being made for profit doesn’t doom a piece of entertainment artistically. |

| ↑14 | Along similar lines, both Jo and Amy lament that seemingly the only respectable way they can make money is to marry into it. This is the most boring part of the movie’s commentary since every modern adaptation of a classic book about women does it, so I only mention it in a footnote. Lest that sound too dismissive, I think there’s a case to be made that a modern adaptation should include that since it’d be unfair for storytellers from the 21st century to condemn Amy for being a gold digger in her pursuit of Fred Vaugn without acknowledging the realities of her historical situation. Alcott, being a single woman in the midst of those historical realities, could do so without hypocrisy. |

| ↑15 | The main difference between this and reality is that Alcott probably wouldn’t have created Bhaer at all unless she had to give Jo a husband. |

| ↑16 | Well, I do know that many casual viewers find it a pain to keep track of which scenes in the 2019 Little Women are flashbacks. It might not have hurt it to sacrifice a little subtlety and include more title cards. |

| ↑17 | That seems like a good point of comparison since, like Little Women, David Copperfield is a very personal novel about the relatable life experiences of a young author. (Both even had movie adaptations directed by George Cukor.) And, like Peter Pan, it’s partly about the relationship between someone who basically wants to grow up and someone who wants to never do so, though the genders are flipped. |

| ↑18 | Though I’d argue it has a few inspired, original moments, such as Betsey Trotwood’s response to Micawber’s claim that he’s not going to make a big speech. And the book is so inspired itself that even a cut and paste job is pretty awesome. |