If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, you may have guessed that I’m interested in the art of animation. This month rather than blogging about adaptations, I’m going to be blogging about a series of animated movies, some of which will be adaptations, some not. Since only my loyal family members read this blog, I trust they’ll be fine with me breaking the rules I set for myself.

Which animated movies should I do? Some would say that Studio Ghibli is the greatest animation studio out there, but while I’ve greatly enjoyed (dubbed versions of) some of their movies, as an American, I wouldn’t understand their cultural context the way I do the cultural context of the other things I’ve covered on this blog. Disney is probably the most influential American animation studio, but I’ve just finished a four-part series on movies produced by the Walt Disney company. So instead, I’m going to write about movies from their rival, Dreamworks Animation. However, their films are more notable for their quantity than their quality[1]That’s not to say all of them-or even any of them-are terrible. Just that they’re far from being consistently great. and the thought of sitting through every last one and coming up with a post for each fills me with dull dread, so I’m just going to look at their four hand-drawn animated movies.[2]Yes, I know they all use computers, but you know what I mean. By the way, I’m just going to count theatrically released hand-drawn movies. I won’t be writing about Joseph: King of Dreams … Continue reading

Whatever your opinion may be of their output, there’s something for which I think Dreamworks deserves credit. In the 1990s, Disney animated movies followed a strict narrative formula and other studios going after their fanbase followed it too.[3]If you’re a big fan of animated Disney movies from the 90s, please don’t take offense. Being formulaic isn’t the worst thing from my perspective, I consider the narrative formula … Continue reading With their hand-drawn animated movies, Dreamworks went places Disney wouldn’t with dark and violent themes, risqué humor and an emphasis on antiheroes and bittersweet endings. In a time when all American hand-drawn animated movies were rated G, or aimed for it at least, three out of four of Dreamworks’s were PG. And in their own ways, they all earn it, even the one that got a G arguably. The four of them don’t really have a formula in common and not one of them feels like it’s trying to be a Disney movie. Sheesh, you could argue that Dreamworks’s computer-animated Shrek, for all its anti-Disney posturing, dances to the Mouse’s tune more than any of their hand-drawn animated movies.[4]Sure, Shrek begins with a page from a fairy tale book being crumpled up and used for toilet paper (literally), but it ends by revealing that its story has become just such another storybook (also … Continue reading Having said that, the downside of not following a formula is that just because you like one of these movies, there’s no guarantee you’ll like any of others. And having given them credit for thinking outside the box, I have to add that it didn’t mean that the dark and violent themes were automatically compelling or the risqué humor automatically funny or the movies themselves automatically good…

The Prince of Egypt (1998)

You can’t criticize Dreamworks for a lack of ambition. Their first hand-drawn animated movie, The Prince of Egypt, takes as its inspiration the biblical book of Exodus. Its protagonist, Moses (voiced by Val Kilmer; singing voice Amick Byram), is born into slavery in Egypt and gets adopted by the royal family in his infancy through an extraordinary chain of circumstances. When he learns of his origins in adulthood, he cannot bear to live a life of privilege while his people, the Hebrews, are suffering and flees into the wilderness. Years later he is called upon by his people’s God to return to Egypt and demand their release. This pits him against Rameses II (Ralph Fiennes who does his own (minimal) singing), his former brother.

Since the story of Moses is part of three major religions and several minor ones, it has a great appeal for Hollywood. But it’s also a challenge since while those religions all revere Moses, they don’t agree on much else and it’s hard to do a movie about him without alienating one group or another. Hollywood also wants its movies to appeal to as many people as possible, so they’re going to want Secularists to enjoy their Moses movie too and that’s not even getting into the artists wanting to make something that reflects their own beliefs. It’s a very difficult balance and, if we’re being honest, probably better off not attempted. But The Prince of Egypt, with its vibe of The Ten Commandments (1956) meets The Lion King (1994), succeeds as well as it ever could and better than you might expect. It may not please everyone-what movie does? Some nonbelievers will find parts of it unrelatable and some believers will take offense at the artistic license it takes, but I do hear both atheists and Christians, the most vocal religious groups in my country[5]I know calling atheists a religious group is questionable, but you know what I mean., praise it and that can’t really be said of any recent film based on the Bible.[6]If you’re interested in which aspects of the adaptation are inspired by which religions, here’s my attempt at a list. As in Hebrew midrash, Moses’s sister predicts he will free his … Continue reading

The part of the Exodus story, at least the section covered by The Prince of Egypt, most likely to offend secularists and humanists is its portrayal of the Hebrews alone as God’s chosen and the horrifying punishments He rains down, not just on Pharaoh who has defied him, but on all the Egyptians.[7]Well, maybe proponents of Critical Race Theory will appreciate that. The movie emphasizes that the Egyptians as a whole are ordinary people, not villains to a man, which is actually less revisionist than you’d think. (The book of Exodus portrays Pharoah’s daughter as having compassion for the infant Moses and the Egyptians as being favorably disposed enough toward their former slaves to give them gold and jewelry as parting gifts.) It even refers to them as “innocents” who suffer for the fault of their ruler. It also scapegoats God, so to speak, and has Moses himself, who was raised Egyptian, be disturbed by the plagues. In theory, the last one strikes me as a lame cheat, but in practice, it actually makes for pretty great drama. [8]And for a prophet to hate the job he has to do is actually pretty consistent with Abrahamic faiths. The scene of God smiting the firstborn of Egypt, arguably the most disturbing plague, has no background music as if the filmmakers are declining to offer judgement on it, which works very well artistically.

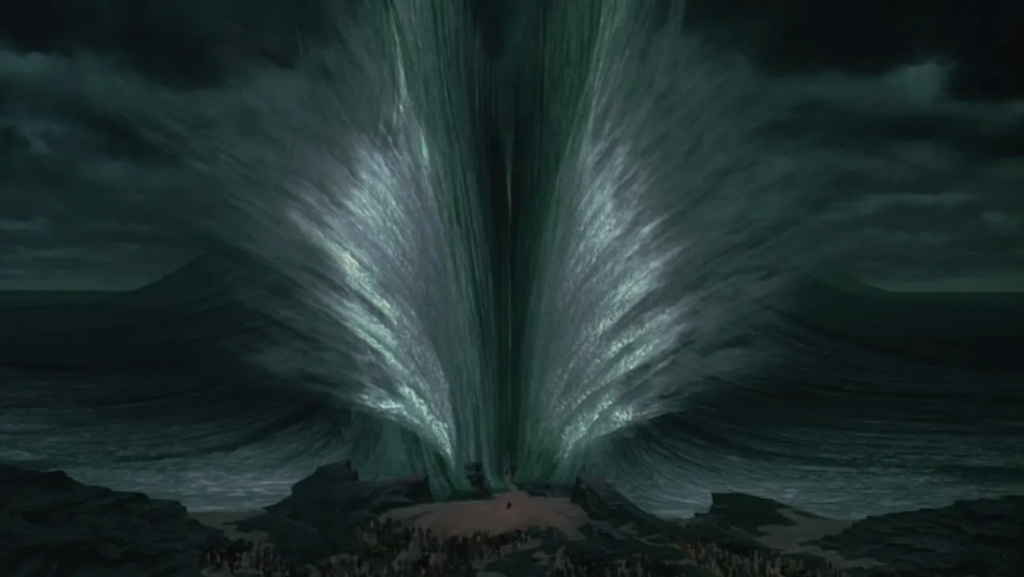

God also plays an unambiguously positive role in the story, preserving and empowering Moses and the Hebrew people. This is most obvious in the numinous scene of Moses encountering Him for the first time and in the climax at the Red Sea but is implied throughout right from the start. The aforementioned scene of God smiting the Egyptian firstborn also emphasizes how the pious Hebrews who obeyed divine commands are protected. The main theological points of the book of Exodus, God’s superiority to all other powers, temporal and spiritual, and His care for His people, are conveyed through the movie’s powerful visual storytelling.

In 2017, a stage musical adaptation of The Prince of Egypt premiered which, from what I understand, emphasized the heroism of the human characters even more and leaned harder into the God-as-villain interpretation. I don’t doubt that was more satisfying for writer Philip LaZebnik and composer/lyricist Stephen Schwartz to work on than the movie since it’s more enjoyable to make a work of art that reflects your own beliefs without having to cater to any particular group. But I’d argue those things actually make the musical less interesting and (ironically) more predictable than the movie was. Broadway musicals that subvert biblical accounts for their own Secular-Humanist purposes are fairly standard. Mainstream animated movies that try to do justice to the traditionally pious take on the Bible, or as much of it as can be reconciled to their own views, are something else.[9]Also the new songs for the stage musical, with a few exceptions, aren’t nearly as memorable as the themes from the original movie, but I digress.

Did I write something about powerful visual storytelling? Yes, I did.

This film’s visuals are technically equal or superior to anything Disney was doing at the time. For sheer eye candy, it may actually be the best thing Dreamworks has ever done. All of the miracles appear to maximum effect and even when nothing supernatural is happening, the movie has an awe-inspiring sense of scale.[10]The colossal monuments and palaces of Egypt are depicted as much larger than they would have been historically. This was a deliberate decision on the part of the filmmakers to make the characters … Continue reading Equally great but less showy is the character animation, which rewards multiple viewings. Pay attention to subtle facial expressions and body language, such as Rameses’s blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reaction to the rather pathetic attempt of his priests (Martin Short and Steve Martin) to duplicate Moses’s miracle of turning the Nile to blood.

Equally powerful and vital to the film are the Broadway-style musical numbers by Stephen Schwartz and score by Hans Zimmer. It’s a crime that so little of the latter is included on the official soundtrack. For its final scenes, the movie uses as little dialogue as possible, letting the music and visuals tell the story by themselves and giving what dialogue there is as much impact as possible. And it is awesome.

The part of the movie with which viewers for whom the source material is sacred are most likely to take issue is its portrayal of Moses’s brother, Aaron (Jeff Goldblum, whose character doesn’t do any singing), as a mostly negative, though not unsympathetic, character who only redeems himself at the end. While there is precedent for Aaron being weak in the Pentateuch, mainly the golden calf incident, he was delighted to be reunited with his brother and was arguably the second biggest hero of the Exodus after Moses. He was also the head of the Levitical line of priests, making him an important figure in Abrahamic religions. The Prince of Egypt‘s depiction is pretty offensive, though I can sympathize with the dramatic reasons behind the change.

The movie’s biggest shortcoming artistically is that while Moses and Rameses emerge as complex and compelling characters,[11]I haven’t given you a good idea of the movie at all by not writing more about their arcs, but to do so might spoil someone’s first-time viewing experience. everyone else’s characterization consists of one or two notes. This is happily more of a limitation than a drawback, but considering how much the camera focuses on Aaron, Moses’s sister, Miriam (Sandra Bullock; singing voice Sally Dworsky), and his wife, Tzipporah (Michelle Pfieffer,) during the final scene, it does seem like we’re supposed to be more invested in them than I think we actually are. I’m not sure how the movie could have developed anyone further though without sacrificing its effective pacing which packs a whole lot of storytelling into a short running time and feels neither slow nor rushed. And, of course, the story is supposed to be about a people, not about individuals. Considering that I’m more interested in stories about individuals than people groups, the fact that The Prince of Egypt works so well for me might just be one of its finest achievements. Downright miraculous really.

Stay Tuned

References

| ↑1 | That’s not to say all of them-or even any of them-are terrible. Just that they’re far from being consistently great. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Yes, I know they all use computers, but you know what I mean. By the way, I’m just going to count theatrically released hand-drawn movies. I won’t be writing about Joseph: King of Dreams (2000) or the various Kung Fu Panda supplementals, but my memories of them are positive. |

| ↑3 | If you’re a big fan of animated Disney movies from the 90s, please don’t take offense. Being formulaic isn’t the worst thing from my perspective, I consider the narrative formula for 90s Disney animation to be very solid as far as narrative formulae go, and at least of their films from this decade, Beauty and the Beast and Mulan, are favorites of mine. But I can see how people actually living through the decade, as opposed to people in the present looking back on it nostalgically, would find it tiresome. |

| ↑4 | Sure, Shrek begins with a page from a fairy tale book being crumpled up and used for toilet paper (literally), but it ends by revealing that its story has become just such another storybook (also literally.) And even the subverted storybook prologue serves to provide legitimate exposition. |

| ↑5 | I know calling atheists a religious group is questionable, but you know what I mean. |

| ↑6 | If you’re interested in which aspects of the adaptation are inspired by which religions, here’s my attempt at a list. As in Hebrew midrash, Moses’s sister predicts he will free his people from slavery long before it happens. God sharing a voice actor with Moses reflects the Jewish tradition that when anyone hears God, He sounds like their own voice. Moses’s motives for leaving Egypt are more in keeping with the New Testament book of Hebrews, which describes him as choosing “to be mistreated along with the people of God rather than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a short time,” rather than him running for his life as in the book of Exodus. (That probably also reflects Jewish tradition.) More debatably, the flames around the famous burning bush visually evoke the fire of Pentecost. As in Qur’an Surah, Pharoah’s wife (Helen Mirren) is portrayed as instrumental in the royal family adopting Moses (and his basket washes up on the shore rather than being left on the bank) and Pharoah threatens to kill the sons of Israel to spite Moses. (Ironically, in The Prince of Egypt, he does this right before God smites the Egyptian firstborn.) Of course, it’s probably an exaggeration to say any of these things were specifically inspired by any religious tradition. Many of them have obvious dramatic appeal and could easily be coincidental. But the movie did have Jewish, Christian and Muslim consultants so who knows? |

| ↑7 | Well, maybe proponents of Critical Race Theory will appreciate that. |

| ↑8 | And for a prophet to hate the job he has to do is actually pretty consistent with Abrahamic faiths. |

| ↑9 | Also the new songs for the stage musical, with a few exceptions, aren’t nearly as memorable as the themes from the original movie, but I digress. |

| ↑10 | The colossal monuments and palaces of Egypt are depicted as much larger than they would have been historically. This was a deliberate decision on the part of the filmmakers to make the characters relatable to viewers familiar with modern skyscrapers. |

| ↑11 | I haven’t given you a good idea of the movie at all by not writing more about their arcs, but to do so might spoil someone’s first-time viewing experience. |