Of all the remakes of George Seaton’s 1947 movie, Miracle on 34th Street, only the 1994 one was released in cinemas. Fittingly, it’s the best of them or at least the most interesting. I don’t consider it anywhere near as good as the classic original. But considering what a classic the original is, this remake really holds up well-well enough to make me wish it was even better, but any way…

Both movies center around an old man known as Kris Kringle, living in a nursing home in New York City, who, depending on how fantastical your interpretation of the material is, either believes himself to be Santa Claus or actually is him. (Either possibility raises as many questions as it answers.) Right before the giant Thanksgiving day parade put on by a major department store (Macy’s in 1947, the fictional Coles in 1994) is about to start, he notices that its Santa Claus could use some instruction on how to crack a whip. He happily gives it and is indignant to discover that the man is drunk on the job. Also not happy with this discovery is Doris Walker, the department store employee in charge of the parade. [1]She’s mostly called Dorie in the remake, but I like Doris better. Desperate, she asks Kris to fill in for him. For the sake of the eager children watching, he agrees and is such a hit that the store hires him to be the official Santa Claus for their toy department. Doris returns home to her apartment to find that her six-year-old daughter, Susan, is in the apartment of her friend and Doris’s wouldbe boyfriend, since she can get a better view from there. Said wouldbe boyfriend is an idealistic young laywer, who is named Fred Gayly in the 1947 movie and Bryan Bedford in the 1994 one. We learn that Doris, stung by the memory of her divorce, has raised Susan not to believe in Santa Claus or fantasies in general as she believes it will only set her up for disappointments later.

Kris goes to work as the department store’s Santa, wearing his own Santa suit, which is much better than theirs. Shockingly, he only recommends parents shop at the store if it has what they want at a reasonable price. If there’s a better bargain on a toy their kid desires at a rival’s, that’s where he sends them. When Shellhammer, his superior, finds out about this, his initial instinct is to throw Kris out on his fat behind. But when multiple grateful parents tell him they’re going to be regular customers from now on, he changes his mind. This eventually becomes the official store policy and Kris becomes a minor celebrity.

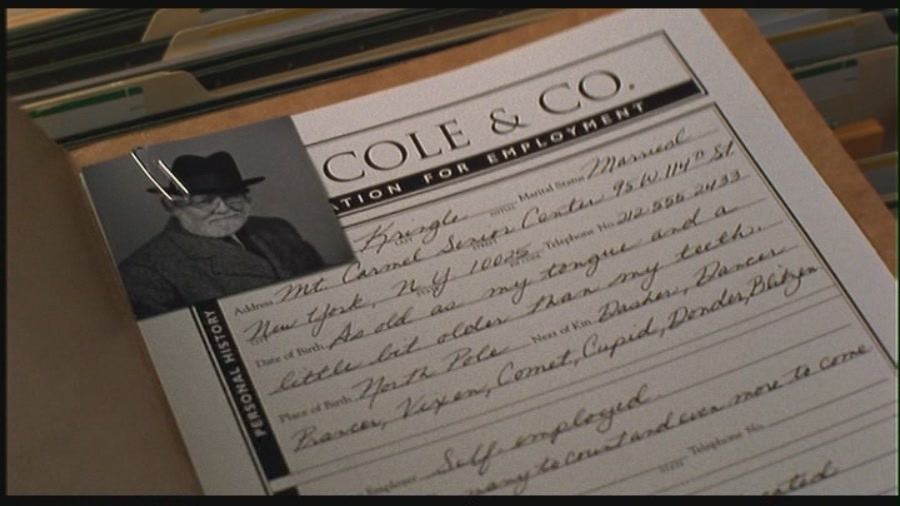

Fred/Bryan, not approving of Doris’s anti-fantasy stance, takes Susan to see Santa. She’s impressed by his warmth, real beard and command of foreign languages. Doris is annoyed by this and gets out his personnel file to show her daughter that he isn’t really Santa Claus. She is horrified to read it and find that the man she has hired to regularly interact with children is apparently a lunatic. She wants to prudently let him go but Shellhammer insists they retain him since he’s so popular.

Thanks in part to Fred/Bryan’s machinations, Susan gets to spend more time with Kris. Wanting to believe in him, but still skeptical, she proposes a test. If he can get her a house like the one in an old magazine clipping that she cherishes, then she’ll believe he’s Santa Claus. Kris tells her he probably can’t but that that doesn’t mean there’s no Santa Claus. Seeing how important it is to her though, he promises to try his best.

Just when everything seems to be going well, a villainous character enrages Kris, in part by implying that anyone who enjoys playing Santa Claus does so for selfish reasons. He hits them over the head and said villain pretends to be injured worse than they actually are. Kris is taken to Bellevue and, devastated by what’s happened, he deliberately fails his mental examination. Fred/Bryan gives him a speech that helps him out of his funk and becomes his lawyer, “proving” in a widely publicized hearing, through means that wouldn’t work in an American court outside of a movie, that he really is Santa Claus. In some point in all of this Doris and her beau have a fight and break up, then they get back together. On Christmas morning, Susan is disappointed to see that Kris apparently hasn’t gotten her that house she wanted, but it turns out he has arranged for her to have it through not-explicitly-magical means, and all ends happily.

You may have noticed that my synopsis got much vaguer during that last paragraph and that wasn’t because I was avoiding spoilers, which I seldom do. (I understand why people don’t want the endings of the stories spoiled, but if you’re talking about how they’re adapted, I feel like changes made to an ending are the most interesting and I don’t know how I’d do this blog if I couldn’t discuss them to some extent.) The second half of the 1994 Miracle on 34th Street takes far more liberties with the original plot than the first half does. Few of them work that well, in my opinion, but let’s not start off with the bad stuff.

Some good stuff-great stuff at its best-is the casting. Sir Richard Attenborourgh’s portrayal of Kris Kringle, which holds up very well next to Edmund Gwenn’s performance. Young Mara Wilson is just as good as Susan as young Natalie Wood was. If anything, she’s better!

Elizabeth Perkins is sadly not better than Maureen O’ Hara was as Doris, a character who could have easily been an uptight joyless prude, but who, in 1947, at least partly thanks to O’ Hara, came across as fun, attractive and good humored in her cynicism. Perkins doesn’t come across as unappealing per se, but she doesn’t avert it as hard as O’ Hara did. Dylan McDermott as Bryan is the only actor I feel is downright miscast, coming across as vaguely smarmy where he’s supposed to be down to earth and inviting.[2]John Payne as Fred in the original movie gave my least favorite of the lead performances in that movie, so maybe it’s kind of fitting.

The script by John Hughes is usually good when it tries to be witty. It’s not as funny as the original was, especially the courtroom antics, but I can watch it and laugh with it without constantly thinking about that. Here’s a sample.

Customer: My kid just asked Santa for a barf gun and the Santa said he’d get it for him.

Shellhammer: I hope the boy likes it. They’re over there by the elevator.

Customer: And they’re ninety bucks without batteries or barf.

Shellhammer: Prices do go up.

Customer: Apparently not at Bargain Village. Fifty two fifty and they throw in the batteries.

Shellhammer: I find it hard to believe Coles could be undersold by that much. Where did you get your information from?

Customer: From your Santa Claus.

Unfortunately, when it tries to capture the original’s emotional aspects, it flounders. Compare this speech from the 1947 movie with one from this.

Fred: It’s not just Kris that’s on trial. It’s everything he stands for. It’s kindness and joy and love and all the other intangibles.

Kris: I’m not just a whimsical figure who wears a charming suit and affects a jolly demeanor, you know. I’m a symbol of the human ability to suppress the selfish and hateful tendencies that rule a major part of our lives.

Both may be sentimental, but the 1947 speech is good quality sentimentality while the 1994 one, which Attenborough, to his credit, delivers like a trooper, is clunky and overwritten as if the movie itself doesn’t believe what it’s saying. (Who exactly insists on their importance by calling themselves a symbol?) But if Hughes and director Les Mayfield were embarrassed by their source material’s sentiment, they evidently decided to blazon it out by outdoing George Seaton in earnest melodrama rather than by backing away from it, failing to realize that it was the 1947 movie’s very restraint that served it so well.

One example of this is how anti-commercialism message is handled. The main villain of the 1994 movie is Victor Lamberg (Joss Ackland), a ruthless businessman seeking to buy out Coles and threatened by the success of their new Santa Claus.[3]Albert Sawyer, the unliscensed psychiatrist with a grudge against Kris, who was the villain of the original movie, is absent here, understandably so since department stores didn’t usually have … Continue reading This character is so over the top I’m not sure if he’s supposed to be a parody of evil businessmen characters or if we’re supposed to take him seriously. “These small seemingly insignificant sentimental anachronisms can be surprisingly potent,” he says of Kris early in the movie, “I don’t want my plans damaged by an elderly cherub in a red suit.” Seriously. That’s an actual line of dialogue from the film. I liked that in the 1947 Miracle, there wasn’t a good store vs. an evil store plot. Both Macy’s and Gimbel’s were indicted in the rampant commercialism surrounding Christmas, and both were willing to do something nice as long as it benefited them.

Something else that’s less nuanced about this version is the character of the prosecuting attorney, here played by J. T. Walsh. In 1947, he was disarmingly portrayed as just a public servant doing his job, unpleasant though it was. Here’s he’s in Lamberg’s pocket and accuses Kris in court of “masquerading as…a figure of benevolence and generosity…solely for profit” and whose freedom puts children at risk, baiting him to get violent in front of everyone. Though, in keeping with the movie’s overall spirit, he turns out to be not such a bad guy in the end.

In general, this Miracle plays the courtroom scenes much more for drama where the original played them for laughs. Remember that line from the 1947 movie about “kindness and joy and love.” That was something Kris’s lawyer says in a private conversation, not in the courtroom where he calmly makes the crazy argument that his client is really Santa Claus. Here he gives big emotional speeches about how Kris shouldn’t be locked up just as the prosecuting attorney gives one about how he should. The last of these pro-Santa speeches ends with the question, “which is worse: a lie that draws a smile or a truth that draws a tear?” which isn’t a sentiment I can get behind, though to be fair, it’s an idea that was never totally absent from Miracle on 34th Street. [4]It’s highly unlikely that Fred or Doris ever literally believe that Santa exists, but for what it’s worth, Kris actually agrees with Doris’s policy of always telling her daughter … Continue reading In both movies, the heroic lawyer’s strategy involves getting public sympathy behind Kris, pressuring Judge Henry X. Harper (here played by Robert Prosky) into ruling in his favor. But in 1947, this was played for wry laughs. This movie has a montage of businesses showing their support and a crowd of people outside the court, eagerly awaiting the outcome and celebrating when it’s a good one. We’re clearly supposed to be inspired by the spectacle of a judge being pressured into giving a ridiculous verdict out of fear of an easily manipulated mob. I’m sorry but I don’t find that inspiring.

The culmination of the attempts to make the courtroom plot more serious-and maybe the ultimate example of how instead of cleverly finding a way around viewers’ cynical defenses, this remake tries to knock them down by directly ramming its head against them, leaving itself with a major headache-is the loophole used to declare Kris Santa. Rather than the comedic post office-related one from the original, here its stated that since the US mint “guided by the will of the people” puts “in God we trust” on dollar bills without any proof, the court can put its faith in Santa Claus without proof. This was probably meant to appeal to theists, but as one myself, I find this offensive, implying that belief in God is the equivalent of believing in Santa. And it makes the movie needlessly pretentious.[5]There’s actually a weird element of religious awareness woven into the script. Bryan has a tradition of saying Grace before Thanksgiving dinner while the Walkers only do it when Susan’s … Continue reading I can appreciate the dramatic irony though that Bryan gets the inspiration for this strategy right after lamenting that money is what destroyed Kris Kringle

I don’t really get the way the movie restructures Doris’s character arc. In the 1947 Miracle, she and Fred break up when she objects to his quixotic defense of Kris. Here he proposes to her, and she turns him down before the Bellevue drama starts. Once Kris is in trouble, she’s the one who reaches out to him and asks him to help. To the movie’s credit, having Doris immediately throw her weight behind Bryan and Kris leads to a great scene that wasn’t in the original where she berates her superiors at work for their statement disassociating themselves from the scandal.[6]She does sort of stand up to her coworkers in the original when she refuses to tell Kris he needs to take another mental exam on the grounds that it would hurt him. But since this ended up crushing … Continue reading But it takes away what little suspense there was in the story’s final section after the hearing as there’s no question whether or not she and Bryan will end up together. Most notably, Doris never encourages Susan to keep believing no matter what when Kris has apparently failed to bring her the present she requested since she’s so clearly a believer at this point that such a scene would feel overindulgent. But without that character beat for her mother, the shaking of Susan’s newfound faith feels pointless and overindulgent anyway. In the original, it was arguably the real climax rather than the court hearing.

Speaking of Susan’s request, another way this Miracle tries to outdo the original in drama is by having her ask not only for a house but for a dad as well, though you could argue that her wanting her a more intact family was always the subtext of that wish. This means that Kris and the script have to contrive a way to have Doris and Bryan marry on Christmas Eve specifically, which they do on a whim without any of their friends or family present. Because that makes sense.

I’m sorry that the main body of this blog post has been about criticizing this movie in the sense of pointing out all its problems and shortcomings because I honestly do enjoy it. In fact, I try to watch it every Christmas, though that’s partly because the season puts me in a forgiving mood. It’s one of those works of art whose virtues are easily summarized, but whose faults take a while to explain, making it sound worse in analysis than it actually is to watch. The second half may be a bit of a mess, but the first half holds up to the classic original pretty well. If only it didn’t try to top it.

References

| ↑1 | She’s mostly called Dorie in the remake, but I like Doris better. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Payne as Fred in the original movie gave my least favorite of the lead performances in that movie, so maybe it’s kind of fitting. |

| ↑3 | Albert Sawyer, the unliscensed psychiatrist with a grudge against Kris, who was the villain of the original movie, is absent here, understandably so since department stores didn’t usually have their own shrinks in the 90s. |

| ↑4 | It’s highly unlikely that Fred or Doris ever literally believe that Santa exists, but for what it’s worth, Kris actually agrees with Doris’s policy of always telling her daughter the exact truth. He just disagrees about what the truth about Santa Claus is. |

| ↑5 | There’s actually a weird element of religious awareness woven into the script. Bryan has a tradition of saying Grace before Thanksgiving dinner while the Walkers only do it when Susan’s grandparents are present. Kris asks if he’s supposed to put his hand on a Bible when he swears to tell the truth in court. Like I said, pretentious. |

| ↑6 | She does sort of stand up to her coworkers in the original when she refuses to tell Kris he needs to take another mental exam on the grounds that it would hurt him. But since this ended up crushing him worse than explaining the situation to him herself would have, it demonstrates weakness more than strength on her part. |