As some of you may know, probably more of you than knew about Jim Henson’s The Storyteller, Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre was an anthology show that ran from 1982 to 1987. Each episode was a retelling of a classic fairy tale, using a loose definition of that genre, with an all-star cast. Many of the episodes were affectionate parodies of their source material. As we’ll see though, some of them played it straight. Not only did the show have big name actors but it usually had sharp writing. The visuals, on the other hand, were terrible at a first glance. Nothing looks good filmed on Video and the show’s use of greenscreen was laughable. But even visually Faerie Tale Theatre could impress. True, the sets and costumes were very obviously fake, but they weren’t trying to look like anything else and, largely thanks to production designer Michael Erler, they could still be lovely. (This show has the word, theatre, in its title, remember? Thinking of it as a filmed stage play should put you in the right frame of mind to appreciate it.) And Faerie Tale Theatre‘s secret weapon was its music, much of which, courtesy of composer Stephen Barber, was legitimately beautiful. The show’s quality wasn’t as consistent as that of The Storyteller, though to be sure it went on for longer and had more opportunities to disappoint. For me, it peaked in consistent high quality with the second season in which every episode was great except for Jack and the Beanstalk, which was actually one of the show’s lamest. Anyway, here’s a rundown of Season 2.

While Faerie Tale Theatre was marketed toward family audiences, its humor tended to be aimed at mature viewers and was sometimes downright raunchy. (What can I say? It was the 80s, a different time.) But there were also episodes that were quite family friendly, which can make it frustrating for parents figuring out whether to watch it with their kids. With that in mind, I’m going to do something I don’t normally do on this blog: include a content warning for each episode, so my readers who are parents of young children can decide which ones to share or avoid sharing with them. My readers who don’t like risqué humor at all may also find these helpful. Those who enjoy it, on the other hand, will be mad at me for ruining the jokes. Sorry, guys.

Rapunzel

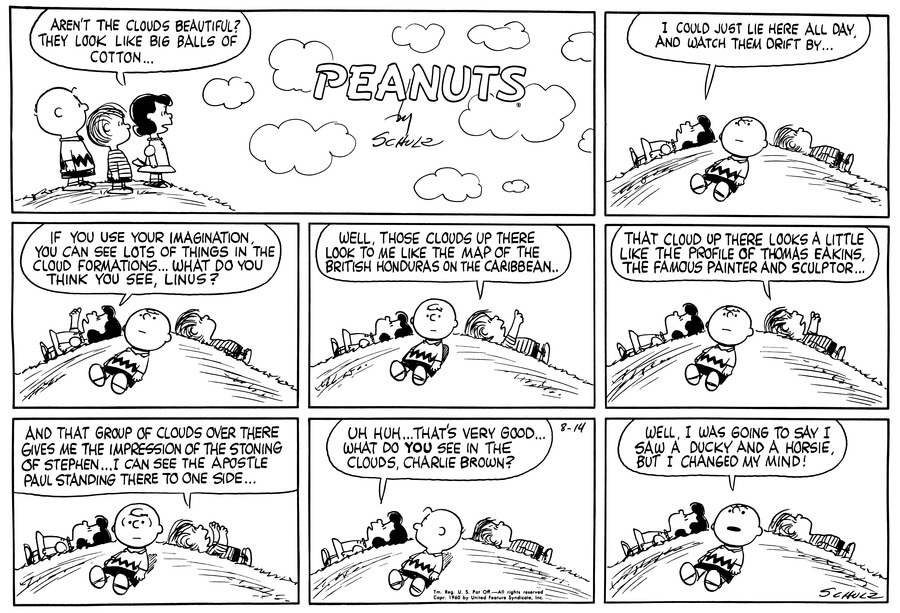

This was the show’s third episode and the first of the second season. If you ask me, this is where they really found their groove. While neither was without its charms, the pilot episode, The Tale of the Frog Prince, written and directed by Monty Python alum Eric Idle, was largely a parody heavy on humor that was inappropriate for kids, and the second episode, Rumpelstiltskin, was a simple straightforward retelling of the story with little or nothing specifically for adult viewers. This episode found a good middle path. It has a fun, lighthearted tone. For one thing, Rapunzel’s mother, Marie (Shelley Duvall who doubles as Rapunzel herself) ultimately convinces her husband, Claude (Jeff Bridges who doubles as the prince) to steal from a dangerous witch (Gena Rowlands)’s garden by saying that her mother was right about him. Yet it sticks close to Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm’s story and even delves into some of its darker themes. A surprising decision it makes is to portray the witch as young and glamorous rather than old and cronelike.[1]Well, glamorous in a 1980s kind of way. It also portrays her as a tragic villainess as much as it can while maintaining that light tone. Her motives for wishing to keep the longhaired heroine from men are strongly implied to be because of traumatic experiences of her own with them. At one point, a rebellious Rapunzel snaps at the witch for never giving her a father. The witch automatically strikes her and then briefly looks horrified by her own actions. There’s also something poignant about how even as Rapunzel is willing to defy the woman who raised her and run off with a near stranger, she can’t bring herself to break the witch’s prohibition against cutting her hair.

Parental Advisory: When Marie initially wakes up craving a radish, Claude suggestively asks if she wouldn’t prefer “a nice cucumber.” When Rapunzel first meets the prince, she curiously asks him if he’s a man. He looks down at himself and says, “I certainly hope so.” He seems eager when he hears that Rapunzel has never met a man before. Once he climbs up to her prison and she gets a really good look at him, she describes herself as feeling “warm and tingly all over and kind of scary too” but “a good kind of scary.” After their first kiss, she asks if it gets any better. He grins and nods. This adaptation retains the twins to which Rapunzel gives birth in the desert though the narrator (Roddy McDowall) explains this for innocent viewers by saying that she and her prince “considered themselves husband and wife” and that their children “were born of love.”[2]In the first edition of the Grimm story, Rapunzel’s pregnancy was what tipped the witch off to her secret relationship. Apparently, they deemed this too immoral for children and had Rapunzel … Continue reading

Worst Special Effect: The animated blood that pours from the prince’s injured eyes and Rapunzel’s magical tear that heals them are laughably bad and sadly ruin what should be dramatic moments.

Funniest Line: Witch: When I find him, I’m going to gouge his eyes out. I’m going to make his brains into soup.

Rapunzel: Mother!

Witch: Now, Rapunzel, don’t be hasty to judge it until you’ve tried it.

The Nightingale

This is one of the episodes that tries the hardest to capture the style of its source rather than playing it for laughs. Of course, since Hans Christian Andersen’s story about a plain bird (here voiced by Shelley Duvall) whose beautiful voice makes it a hit at the semi-tyrannical emperor of China (Mick Jaggers)’s court until the courtiers grow to prefer an easily controlled and shinier clockwork bird, already had laughs. But those reflected Andersen’s sense of humor, not necessarily Faerie Tale Theatre‘s sense of humor. The script by Joan Micklin Silver stays very close to the style and content of the source material. The biggest addition being the expanded role of the kitchen maid (Barbara Hershey giving one of the most dramatic performances seen on Faerie Tale Theatre) who leads the court to the nightingale. This version gives her a vital relationship with the emperor. The production design, inspired by the art of Edmund Dulac, are beautiful and so is the soundtrack by Stephen Barber. The climax where the embodiment of death itself (Bobby Porter) comes for the ailing emperor is one of the most legitimately creepy things to appear on this show. Kudos to director Ivan Passer for this episode! If only the series’ take on The Snow Queen had done as much to capture to feel of Andersen’s writing.

Parental Advisory: No sexual innuendo that I can remember. Particularly young or sensitive children may not care for that creepy climax though.

Worst Special Effect: Nothing. Well, all of the effects are dated but none of them jars me out of the viewing experience as much as stuff on Rapunzel.

Funniest Line: Imperial Chef (Charlie Dell): For Your Imperial Majesty’s most royal gratification, a gently roasted suckling pig raised exclusively on lambkins and glazed with the honey of rare Himalayan bees.

Emperor: Haven’t I tasted this before? Some years ago? In the springtime?

Imperial Chef: Oh no, Your Majesty! That suckling pig was glazed with the honey of rare cashmere bees.

Sleeping Beauty

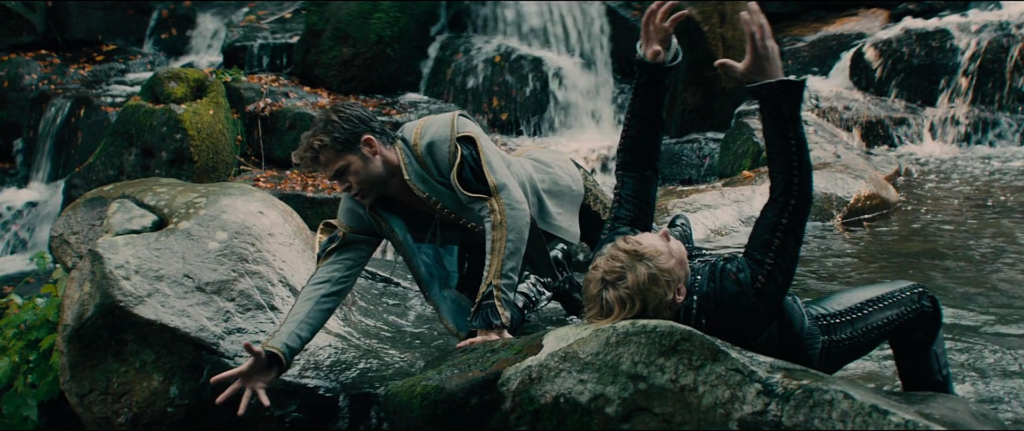

This episode officially credits Charles Perrault for its source material but like most retellings of this story, it’s really a combo of the Grimm and Perrault versions. The costumes and names however set the events in Russia rather than Germany or France, a nod to the Tchaikovsky ballet from which this episode draws its soundtrack. (Lennie Niehaus adapted the score.) One thing both Perrault and Grimm have is an old man who informs the wandering prince (here played by Christopher Reeve) of the enchanted castle’s history. In this version, the prince also tells the woodsman (George Dzundza) about his failed attempt at romance with an exotic princess. Bernadette Peters plays both said princess and the Sleeping Beauty who is the prince’s true love. And in her backstory, Christopher Reeves also plays an unwanted suitor of hers. This double casting allows Reeves and Peters to show off their range and they make the most of it. Next week, I intend to write about how I feel this show often suffers from bland lead performances. Happily, that’s far from the case here.

The script by Jeffrey Alan Fiskin is full of comedy in the vein of Faerie Tale Theatre, much of it cynical and very, very funny. I love the characters of Henbane (Beverly D’ Angelo), the fairy who curses Sleeping Beauty, probably one of the show’s most fun villains, and the younger, more benevolent fairy (Carol Kane) who saves the princess. (“Between you and me,” she confides in her, “let’s just hope there’s a prince out there with more courage than brains.”) But Reeves is unwaveringly earnest as the noble hero, playing the role with only the slightest hint of irony and delivering his big romantic speech at the end with all the conviction of a Shakespearean soliloquy. Peters also gives a highly dramatic performance as the equally noble heroine, one without even a slight hint of irony. The scene where she has to pretend to be fine with marrying a stranger for the sake of her royal father (Rene Auberjonois) manages to be a real tearjerker. This episode is both highly snarky and highly sincere. Theoretically, those two sides of it should clash but they end up balancing each other out, making for both an entertaining parody and something genuinely romantic and moving.

Parental Advisory: This is definitely one of the most risqué episodes. When we first meet the king and queen (Sally Kellerman), it looks like they’re about to have sex, only to reveal that the queen is going to read her husband a bedtime story as she does every night. When she expresses a desire for a child, a fairy spirit (uncredited) appears and (inaudibly) explains to the couple how to make one. In another scene, the chaste prince’s aforementioned anti-love interest tries to seduce him by promising to donate all of the pearls that line her top to the poor if he plucks them all off while she’s wearing it. The prince is embarrassed to relate this, but the woodsman is eager to hear every detail and is disappointed to hear that nothing ultimately happens between the two. There are some other naughty jokes in the episode but if you don’t have a problem showing it to kids yet, I doubt anything else will convince you.

Worst Special Effect: Not only does the prince have to get through a forest of briars in this version, they come to life and attack him. They’re very obviously puppets. Then, taking a page from the Disney movie, Henbane, the evil fairy, turns herself into a giant reptilian monster and he has to fight his way through her. This awkward fight scene is staged with a projected image of a battle between an army and a dragon in the background, which shatters when the prince hits Henbane with a weapon. This all looks ridiculous, of course, but to the credit of Reeves and the episode, they actually manage to kind of sell me on the scene.

Funniest Line: Yellow Fairy (Carol Smith): It is my honor to bestow upon the princess surpassing beauty.

Green Fairy (Gene Varrone): That old chestnut! You’d think after three hundred years, she’d be able to come up with something original!

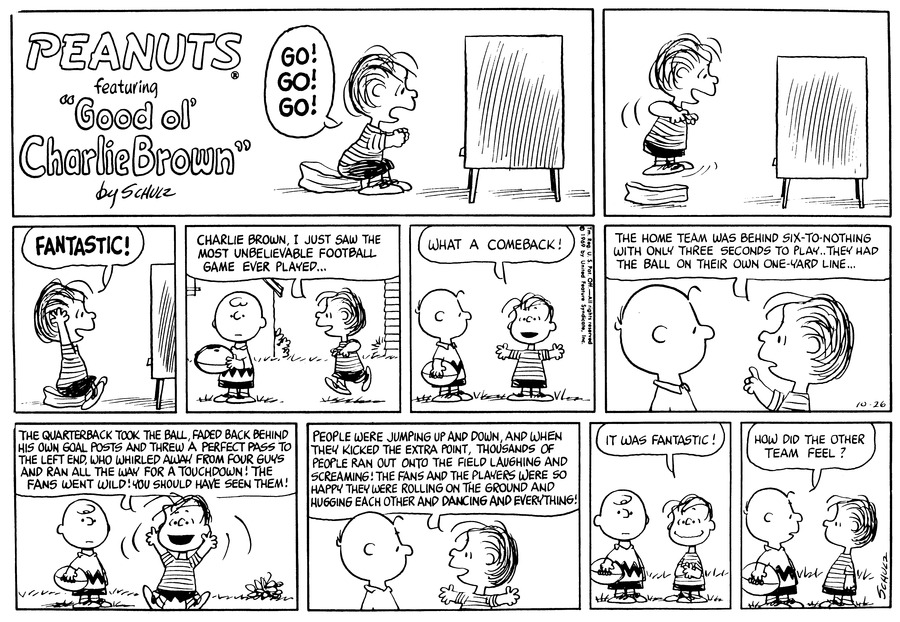

Jack and the Beanstalk

Right after that sterling episode, we get the one clunker of the season, arguably the clunker of the whole show. Most of the actors’ performances, including those of Dennis Christopher as Jack and Elliot Gould as the giant, are very cartoony, which would normally be what would you’d want, given the farcical writing, but there’s good over-the-top and bad over-the-top and after a while, everyone becomes off-putting and vaguely grotesque. While it’s typical for Faerie Tale Theatre‘s sets to be obviously fake, they’re hardly ever as drab and unimaginative as the ones in this episode. Even the music by Frank Serafine, not a regular composer for the show, is boring and if you’ll remember, I described the music of this series as its secret weapon.

Some versions of this fairy tale, such as Andrew Lang’s, have Jack meet a fairy at the top of the giant beanstalk who explains to him that the giant (or ogre) is the one who killed his father and stole his treasures, justifying Jack’s thievery. Often this fairy is connected to the old man who gave Jack the magic beans. Faerie Tale Theatre does this too, having them be the same person but rather than having the fairy disguise herself as the old man, it has the old man (Mark Blankfield) disguise himself as the fairy! Theoretically, this is funny but in practice, it just comes across as awkward. (Basically, this episode in a nutshell.) Blankfield is annoying in both roles. He also narrates and he’s even disastrous at that, sounding like he has a stuffed nose the whole time. And yet…I still enjoy this episode. I’ll even say I enjoy it more than the series’ Rip Van Winkle episode, which is probably superior technically. The script by Mark Curtiss and Rod Ash, frequently collaborators for Faerie Tale Theatre and Duvall’s follow-up show, Tall Tales and Legends, is reasonably amusing. (“You know what?” the giant glumly tells his wife, the giantess (Jean Stapleton.) “I figured out today that when you die, you’re dead.”) It’s mostly the execution that’s bad. As Jack himself says to his mother (Katherine Helmond) early on, “we haven’t hit rock bottom. We’re just not exactly on the top.”

Worst Special Effect: The whole affair is so visually unappealing, why bother to choose?

Funniest Line: Jack (when the giantess tries to hide him in her oven): You know this is not Hansel and Gretel, don’t you?

Giantess: I’m an ogress, not a witch.

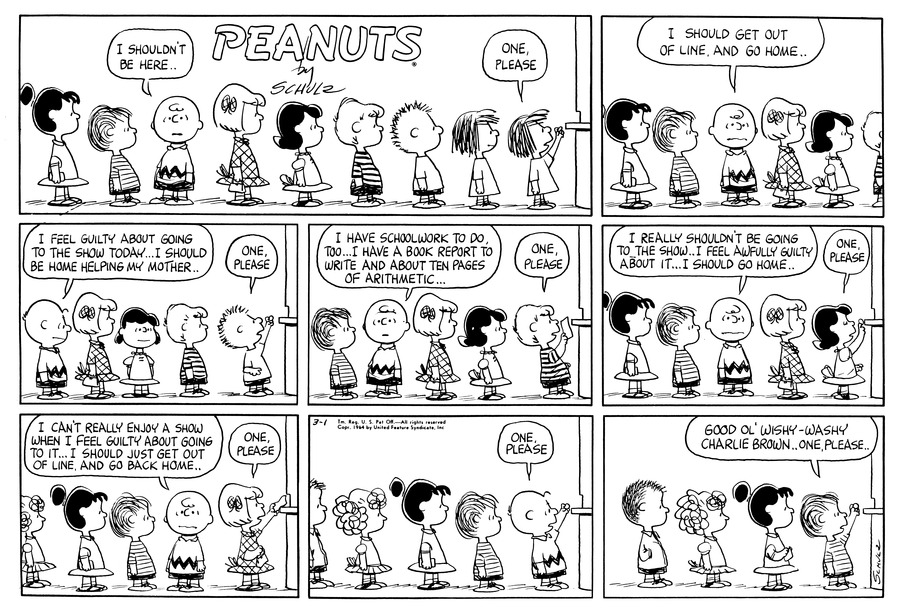

Little Red Riding Hood

This episode’s script by J. David Wyles, who also wrote the one for Rapunzel, and Mark Curtiss and Rod Ash, is one of the series’ funniest and most quotable. (When the wolf (Malcolm McDowell) tries on Granny (Frances Bay)’s nightgown for a disguise, he laments that “the woman hasn’t bought anything new in twenty years!”) Everyone in the cast relishes their two-note performances. Watching them, you think, “this is what Jack and the Beanstalk was supposed to be like!” The episode’s story may certainly be padded, mostly with material involving Little Red Riding Hood’s overly strict father (John Vernon), her perky, cleanliness obsessed mother (Diane Ladd) and her bashful wooer, young woodcutting apprentice Christopher (Darrell Larson), but it’s all such fun padding that who cares?

Parental Advisory: This isn’t so much a sexual joke as it is sexual subtext but this episode, like the Charles Perrault version of the story, has the wolf, disguised as Granny, ask Little Red Riding Hood to get into bed with him, ostensibly to warm him up, prior to eating her. This will probably go over children’s heads. There’s some fleeting profanity in the dialogue and the very young may be disturbed by the scenes where it’s implied the wolf eats Granny and Little Red.[3]Don’t worry. The episode follows Grimm in having them be rescued from its belly. Others will just laugh at the campiness of it all.

Funniest Line: Mother: Now one more problem. Which of your very special friends would you like to invite to the party?

Little Red Riding Hood: Well, Mother, that’s just what I wanted to talk to you about. I never go out; I don’t have any friends.

Mother: Splendid! Now, you see, whenever we put our heads together, we can solve any problem.

Hansel and Gretel

After that delightfully tongue-in-cheek episode, we get one of the show’s most dramatic and least played for laughs. As with The Nightingale, this episode earnestly tries to capture the style and tone of its source, in this case, the story immortalized by the Brothers Grimm.[4]Though it also ends up owing something to Humperdinck’s opera version. For one thing, the script by Patricia Resnick contains an unusually high number of references to God. This is the only Faerie Tale Theatre episode to use actual child actors (Ricky Schroder and Bridgette Anderson) for its young leads. While some of their line readings aren’t as polished as those of more experienced thespians would have been,[5]In their defense, the dialogue isn’t trying to sound like real people talking and can be rather complex. they make it up for it with real vulnerability. This is also one of the only episodes to use real locations and they work far better to convey that Hansel and Gretel are hopelessly lost in the wilderness than even the scariest of painted backdrops.

If there’s anything about this episode that does feel tongue-in-cheek, it’s Joan Collins’s over-the-top performance as the ravenous, child-eating witch. (She doubles as the stepmother and does a great job differentiating the two villains.) I don’t necessarily mean that as a criticism; it’s great to watch her chew up the scenery like its bubblegum.[6]Actually, Hansel and Gretel also chew the scenery when they arrive at her gingerbread house. Get it? Chew the scenery? (“Since I have no other virtues, there is no reason for me to have patience,” she says at one point.) If I do take any issue with this adaptation, it’s that it omits Hansel and Gretel finding gold and jewels in the witch’s house, leaving it an open question how their impoverished father (Paul Dooley) will be able to provide for them once they’re reunited. Maybe Resnick felt he needed to redeem himself by taking them back without anything to gain by it? Anyway, this still stands as one of Faerie Tale Theatre‘s best attempts to explore the serious themes of its source material and a worthy close to its most consistently great season.

Parental Advisory: This is less of a joke than a plot point. The stepmother tells her husband that after they abandon Hansel and Gretel, once the famine in the land is over, they can always have more children. “We can start now if you like,” she says flirtatiously, “having more children.” When he urges her to be quiet lest they wake Hansel and Gretel, she says, “tomorrow (when they’re gone) we can start to make noise again.” Other than that, this is probably the most kid-appropriate episode of Faerie Tale Theatre, though the very young may be scared of the witch.

Funniest Line: Witch: I’m about to teach you something very useful. How to turn a child’s heart into gingerbread.

Gretel: I’d rather learn to read.

I know I just praised Hansel and Gretel for delving into its source material’s serious themes but what struck me rewatching the show recently was how each of these episodes, even the ones played most strictly for laughs, has something going on in its head. Sleeping Beauty preaches the virtue of patience.[7]The same moral, incidentally, that Charles Perrault attached to the story though he joked that expecting his feminine readers to wait a hundred years for a good husband was too much. Jack and the Beanstalk, by contrast, preaches the importance of taking initiative. Rapunzel explores possessive, paranoid parenting. Hansel and Gretel, on the other hand, explores child abandonment and the importance of familial solidarity. Little Red Riding Hood reminds us of the sad necessity of learning by experience. The Nightingale is a satire of the nature of celebrity and contrasts flashy, faddish, soulless art with modest yet timeless art that has heart. Faerie Tale Theatre may be too dated to be described as timeless but it’s happily closer to the latter than the former.

Next week I’m going to look at great episodes from other seasons of Faerie Tale Theatre, episodes nearly as great as the majority of Season 2 and all of them better than the Jack and the Beanstalk episode.

References

| ↑1 | Well, glamorous in a 1980s kind of way. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In the first edition of the Grimm story, Rapunzel’s pregnancy was what tipped the witch off to her secret relationship. Apparently, they deemed this too immoral for children and had Rapunzel make a stupid slip of the tongue instead in their second edition. Yet they still mentioned the twins in the end so there was still the implication that the prince and Rapunzel had sex out of wedlock, only without it serving any plot function. Sometimes the Grimms’ thought processes were hard to follow. |

| ↑3 | Don’t worry. The episode follows Grimm in having them be rescued from its belly. |

| ↑4 | Though it also ends up owing something to Humperdinck’s opera version. |

| ↑5 | In their defense, the dialogue isn’t trying to sound like real people talking and can be rather complex. |

| ↑6 | Actually, Hansel and Gretel also chew the scenery when they arrive at her gingerbread house. Get it? Chew the scenery? |

| ↑7 | The same moral, incidentally, that Charles Perrault attached to the story though he joked that expecting his feminine readers to wait a hundred years for a good husband was too much. |