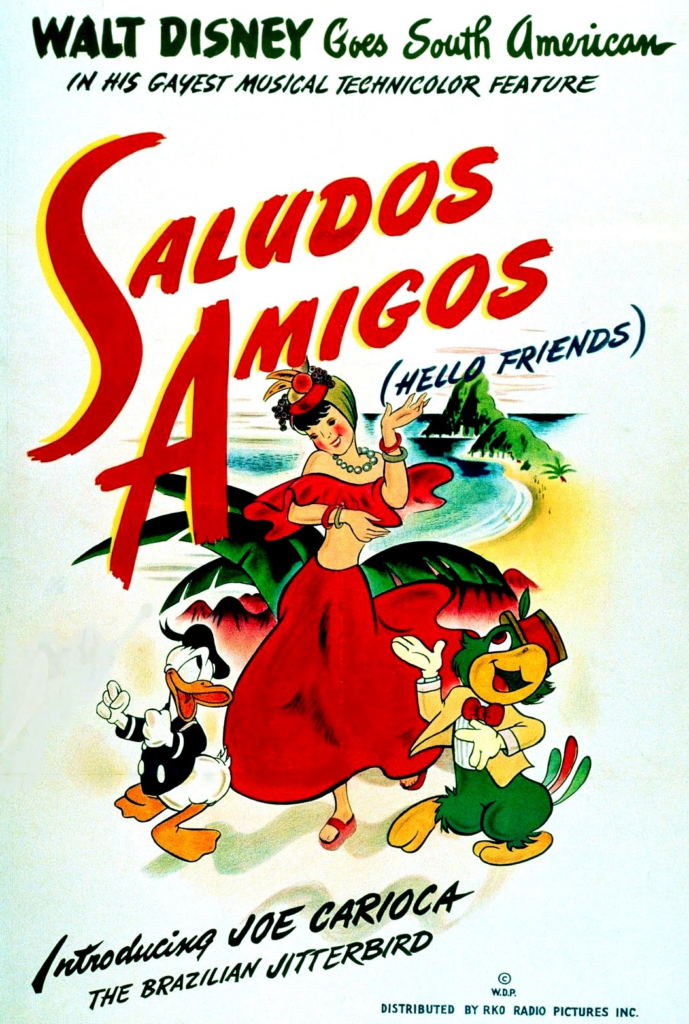

I admit one of my biggest hurdles when I started off on this series was the thought of reviewing Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros, which I remembered as being the most boring of the Disney anim-anthologies. It’s true that I described Fantasia as boring or potentially boring and I still love that, but it feels like it’s being intentionally boring. These two movies are trying to be fun and often failing at it. Fortunately, they’re both so fluffy that I think I can cover them in one fast paced blog post.

These films, or at least the first of them, are actually the result of the US government asking Walt Disney to take his animators on a tour of South America to make a movie about it as part of the United States’ Good Neighbor policy. The resulting pieces of cinema turned out to be more about explaining South America to North America rather than vice versa. If people in Latin America were really keen to see Disney cartoon stars interacting with their cultures, I find it odd that Donald Duck and Goofy, mostly the former, were featured in these movies but not Disney’s main icon, Mickey Mouse. Maybe Donald and Goofy were mad about not being in Fantasia. Maybe Mickey knew these movies weren’t going to do anything for anyone’s career. Anyhow…

Saludos Amigos (1942)

We begin with documentary footage of Disney animators boarding a plane while a voice-over narrator (Fred Shields) explains what’s happening. Then we see an animated version of the plane flying over a map of South America and the four areas on which this movie focuses are highlighted.

First, we get some footage of Peru, specifically the neighborhood near Lake Titicaca. We see the Disney artists sketching the things they see while the narrator explains about them. He doesn’t get into much depth and it’s all rather dry and dull. The part that talks about llamas made me think wistfully about watching The Emperor’s New Groove instead.

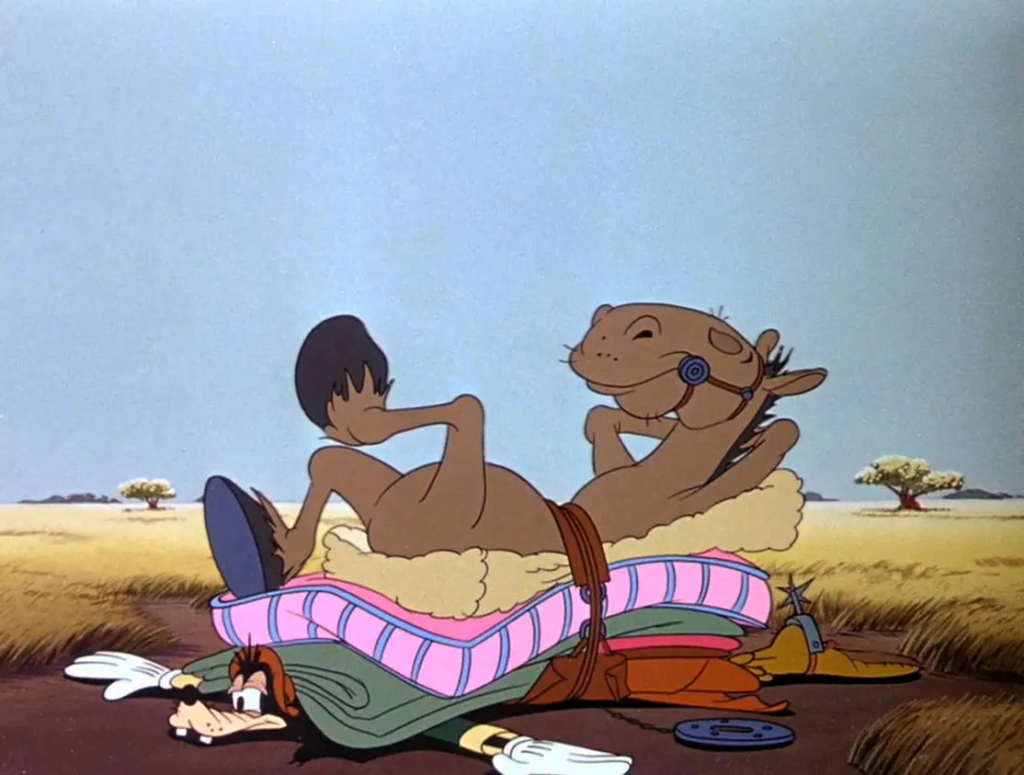

Then we get our first real cartoon, one featuring Donald Duck (voiced by Clarence Nash) as an American tourist. It starts out pretty dull with visual gags that are basically fine, but which should be familiar to anyone who’s watched Disney animated shorts from this time period. It gets much more fun and visually engaging halfway through though, when Donald buys a llama that responds to pipe music and the two of them then have to cross a precarious rope bridge.[1]Now I’m really reminded of The Emperor’s New Groove!

We then get footage of the Disney tourists flying over the Andes. The narrator informs us that learning about the planes that deliver mail inspired the next short, which is about a family of anthropomorphic aircrafts, the youngest of whom, Pedro, has to take such a flight when his parents are sick.

It’s pretty ho-hum. The best things about it are the design of the mountain which menaces little Pedro and the twist at the end about just what the letter for which our hero risked so much contained.

More dull documentary stuff follows, this time showing the animators in the Argentinian Pampas, studying gauchos and folk dancing.

It feels like it goes on a long time without telling us anything interesting about its subject, but since the last bit of live action footage we got was unusually brief, maybe they felt they had to make up for it.

Our next cartoon features Goofy (Pinto Colvig) as a Texan cowboy who gets transplanted across the border to become an Argentinian gaucho. It’s got some good funny moments, mostly to do with contrast between what the narrator describes and what actually happens onscreen. But most of them are near the beginning and I was soon ready for this part to be over.

The final documentary section is about Rio Janeiro in Brazil, ending with a carnival. Forgive me for being ignorant of just what the carnival is about. Like I wrote, despite being ostensibly about explaining South American cultures to American audiences, Saludos Amigos doesn’t go into much depth.

Apparently, the carnival is an annual thing though. “Each year hundreds of songs are written especially for this occasion,” says the narrator, “and the dream of every composer is to have his song chosen as a Carnival hit. One number stood out as a perfect background for the first Brazilian film. Its author, Ary Barroso, has made use of the samba rhythm to paint a musical picture of his native land, Aquarela do Brasil, a watercolor of Brazil.” Naturally, the cartoon that ensues features an actual painting of Brazil. We see a giant paintbrush creating a Brazilian jungle and its inhabitants.

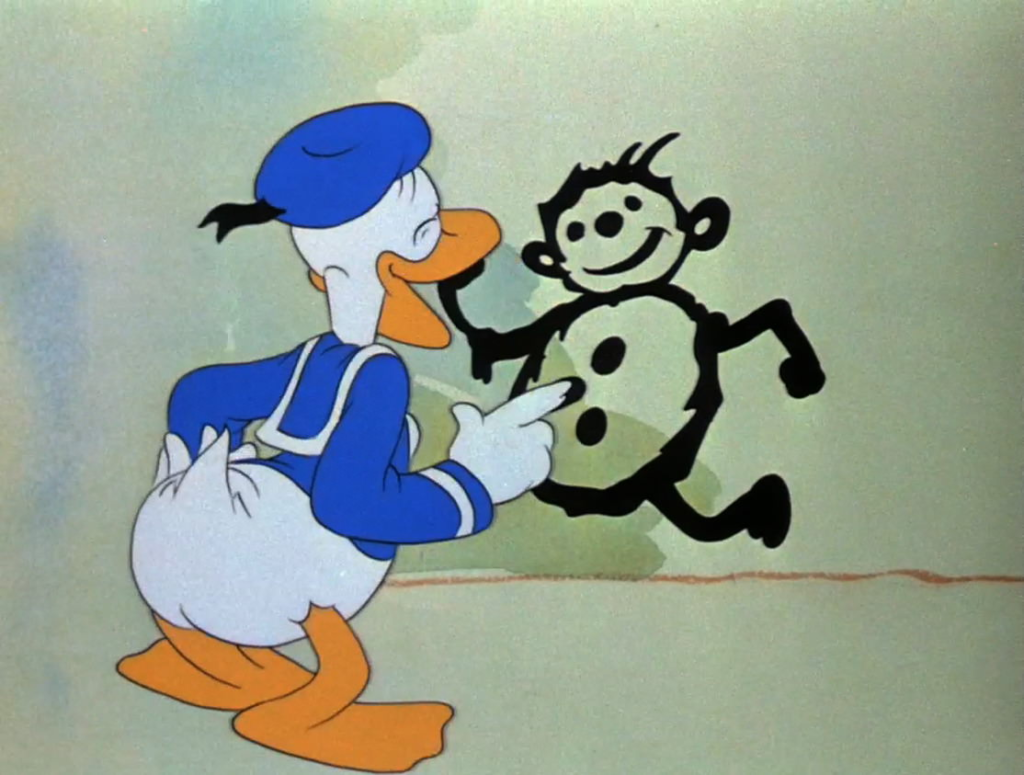

One of those inhabitants, or rather the lone tourist, is Donald Duck. There are some bits with him and the paintbrush interacting that are quite funny even if they do make me wish I were watching Daffy Duck in Chuck Jones’s masterpiece, Duck Amuck.

Donald meets Jose Carioca (Jose Oliveira), a character created specifically for this movie, who takes him out for a night on the town.

Jose’s stereotypically Latin temperament is a bit overwhelming for Donald but not enough for it to be particularly hilarious.

Like Fantasia before it and most of Disney’s anim-anthologies after it, Saludos Amigos comes to an abrupt halt at the end. An especially abrupt halt in fact. The movie clocks in at about 42 minutes. Yet it still feels long and somewhat boring.

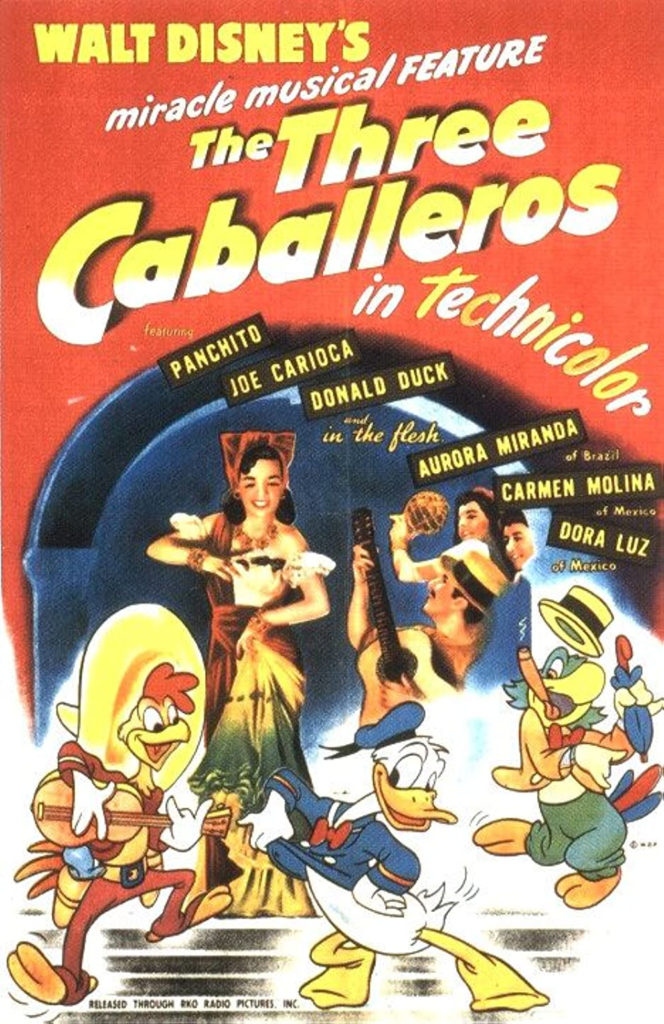

The Three Caballeros (1944)

This movie’s framing material takes place against a plain dark background. I don’t know enough about animation to say whether this was done because it was somehow cheaper than a regular backdrop, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that was the case.[2]From what I understand, the Disney company was not exactly rolling in dough when it made these movies. I’ll try to explain in the next post. The movie begins with Donald Duck receiving a huge package of birthday presents from his friends in South America.

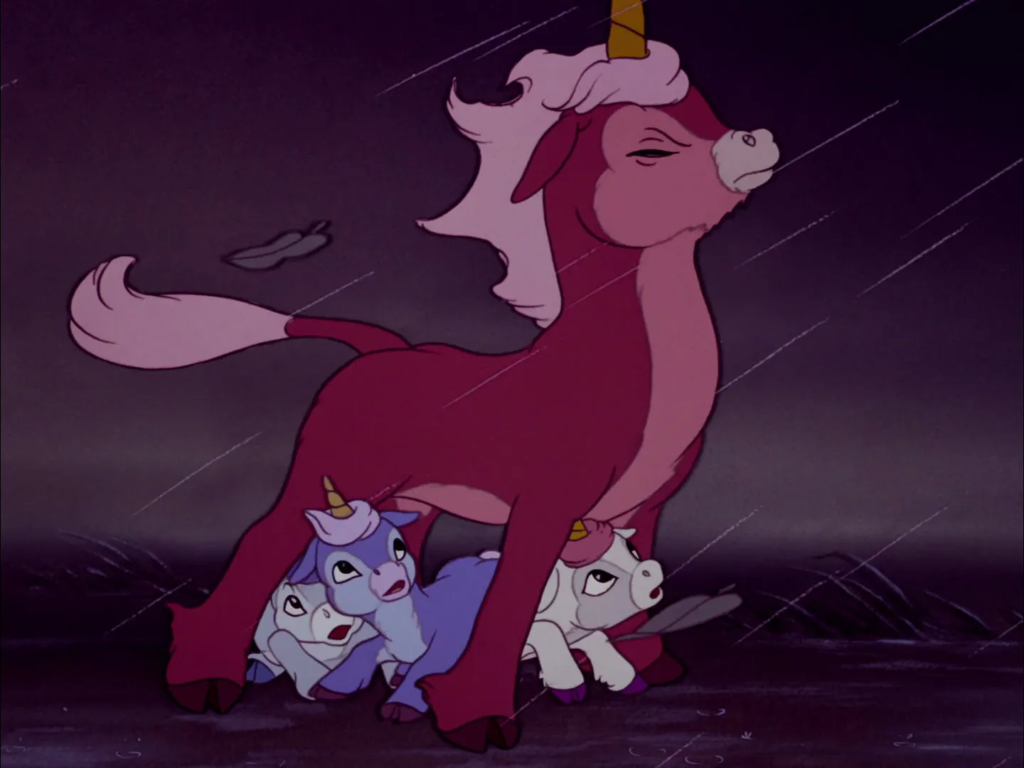

The first one he unwraps, which, unlike the others, isn’t from a specific country, proves to be a film strip of a “documentary” about rare birds. It consists of three parts. The first is a cartoon short about a penguin named Pablo who hates the cold and sets out on a perilous trek to the Galapagos Islands, which are part of the republic of Ecuador and so, I guess, count as South American.

If you’re wondering why I didn’t identify Pablo’s voice actor, it’s because he doesn’t have one. The only vocal work in this part comes from veteran Disney voice actor Sterling Holloway who narrates. He’s hilarious, though I’m not sure if this needed narration at all. The visuals do a great job of telling the story by themselves. I was pleasantly surprised by how many great gags there were here.

We then shift to something closer to an actual documentary with narrator Frank Graham sharing facts about Latin American birds. It’s not nearly as much fun as what just preceded it, though there are a few amusing moments.

It introduces the Aracuan bird who escapes from the screen and pops up once or twice later to annoy the other characters. He’s not very funny if you ask me.

The “rare birds” section of The Three Caballeros concludes with a story that turns out not to be about birds at all. A third narrator (Fred Shields again) tells of how when he was a Uruguayan gauchito he captured and tamed a winged burrito[3]As in little burro, not the food. and then illegally entered him in a horse race.

This short is more fun than the bird stuff that preceded it but not as funny as the Pablo part. The best bits involve the narrator, though I’m not sure how his being an older version of the protagonist squares with the ending. It’s interesting, to me anyway, that all the Disney anim-anthology movies share basically the same sense of humor yet vary drastically in how funny they are-and, for that matter, how funny different segments within the same movies are.

On the whole, the rare birds section of The Three Caballeros is probably the least weird part of it, which, considering that it involved a heat loving penguin and a flying donkey, should give you some idea of how crazy it gets.

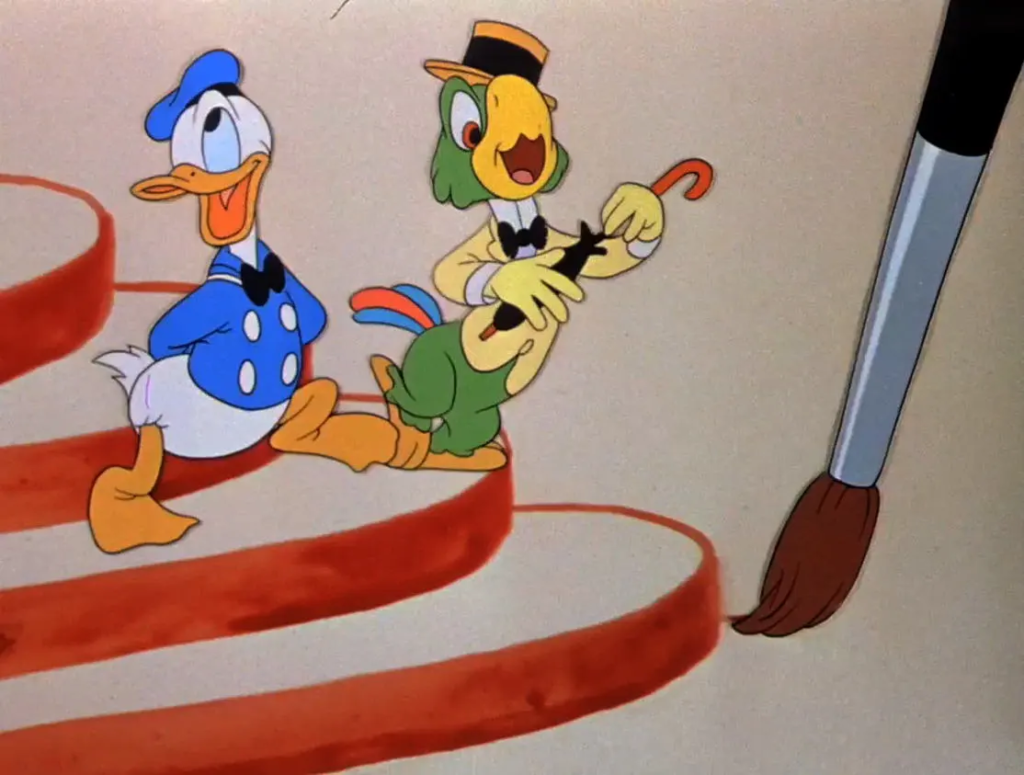

The second present Donald opens is a popup book about Brazil. It opens to reveal a miniature Jose Carioca.

Jose sings a rather boring song about Baia which is accompanied by some equally uninteresting tracking shots of the state.

Then Jose splits into a bunch of clones and sings another livelier song about the same place.

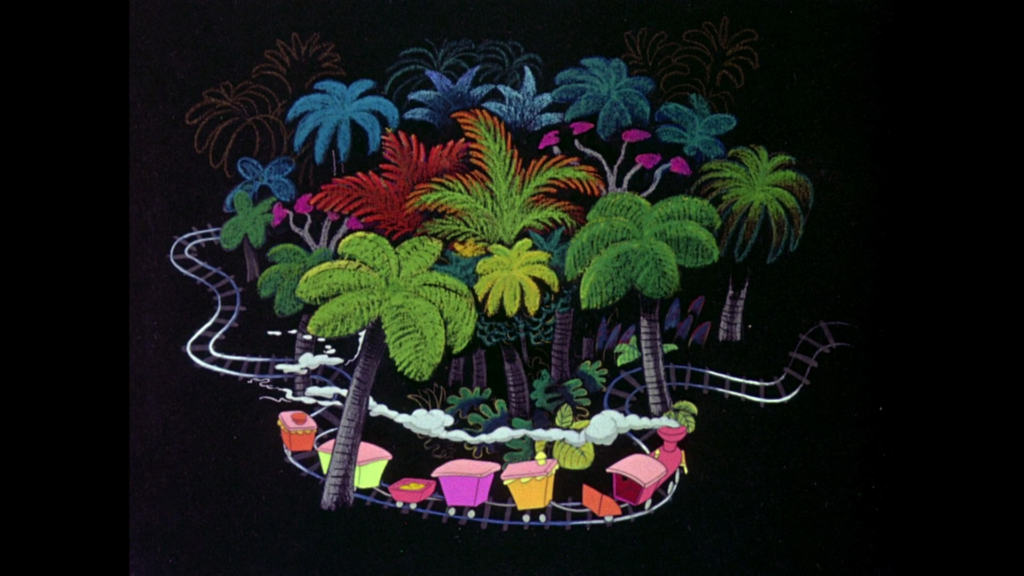

The punchline to all this is that he’s never actually been there himself. But that can be remedied. He shrinks Donald down to his own size and the two of them board a train in the pop-up book. This leads to some interesting backgrounds evocative of chalk drawings.

But it also turns out to be unnecessary since what actually gets them to Baia is turning the pages in the book. Donald and Jose both try to flirt with singer Aurora Miranda, but to their annoyance a bunch of male samba dancers appear and steal their thunder.

I’m not kidding. At one point, Donald gets so mad he almost commits murder.

He eventually gets lucky after giving Miranda a bouquet.

Then the scene gets really weird as we see two of the dancers fighting[4]Or dancing? It’s hard to say. in silhouette who briefly turn into roosters and the very backgrounds come to life and join in the dance.

The song, Os Quindins de Yaya, isn’t particularly to my taste and the scene goes on far too long, but I have to admit parts of it are enjoyable.

I have to give the movie credit too. I thought it would forget that Jose and Donald had shrunk, but once they’ve emerged from the book, Jose shows Donald the magic trick for restoring them to their normal sizes. Donald initially bumbling it is actually the funniest part of the film.

Donald opens his third gift to reveal…well, it’s hard to describe. First, we get a parody of the Meet the Soundtrack part of Fantasia. Since Fantasia was understandably not a huge box office draw upon its release, I have no idea what the Disney animators were doing, parodying a movie they couldn’t expect audiences to recognize. But as a Fantasia fan, I’m sure grateful they did.

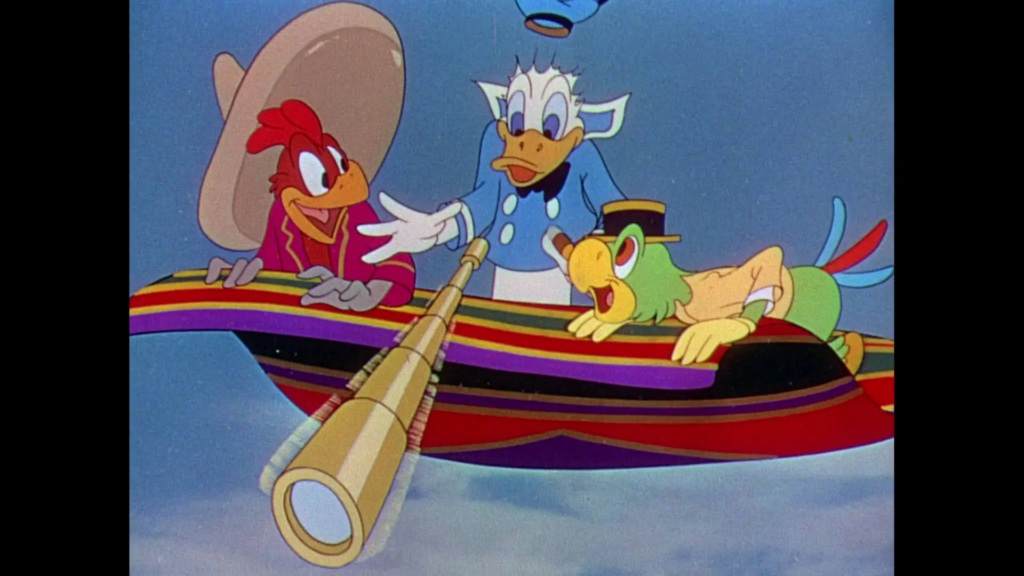

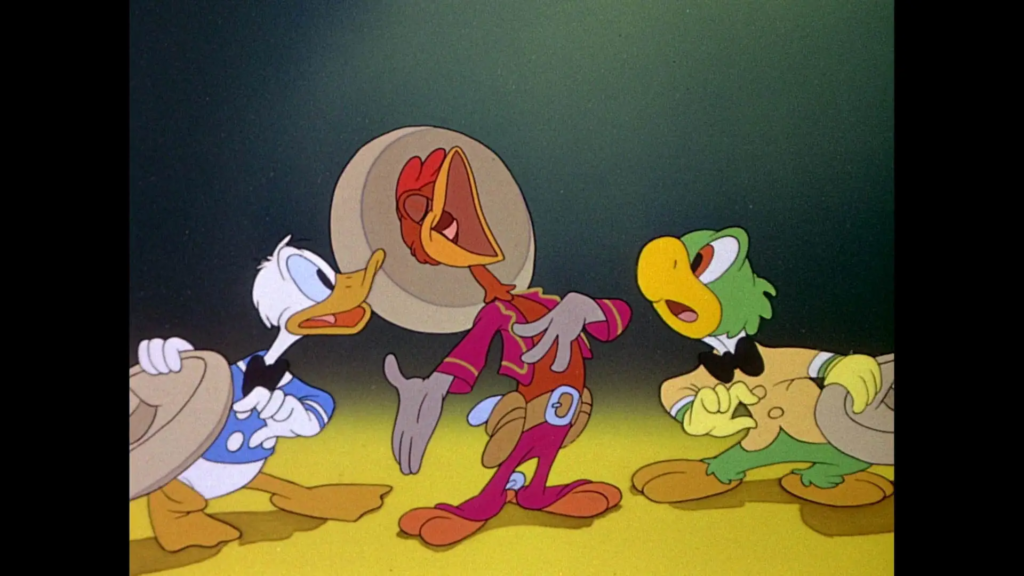

Then we meet Panchito (Joaquin Garay), a raucous rooster vaquero, who passes out sombreros and declares himself and the other two birds to be “three caballeros.”[5]I assumed caballero meant cowboy but, no, it apparently means gentleman or gallant.

Our newly dubbed heroes launch into the title song, which is something of a hidden gem, a catchy tune with clever lyrics. And the accompanying animation is also fun. But neither Panchito nor the unexpected Fantasia parody were actually Donald’s present. No, that turns out to be a big piñata. Donald is eager to crack it, but first Panchito explains about Mexican Christmas traditions and shows pictures of them.

Donald eventually smashes the piñata to reveal a plethora of Mexican paraphernalia[6]Wait. Mexico isn’t part of South America! including a giant guidebook. Panchito opens it and gives another lecture, this one on the history of the Mexican flag and Mexico City.

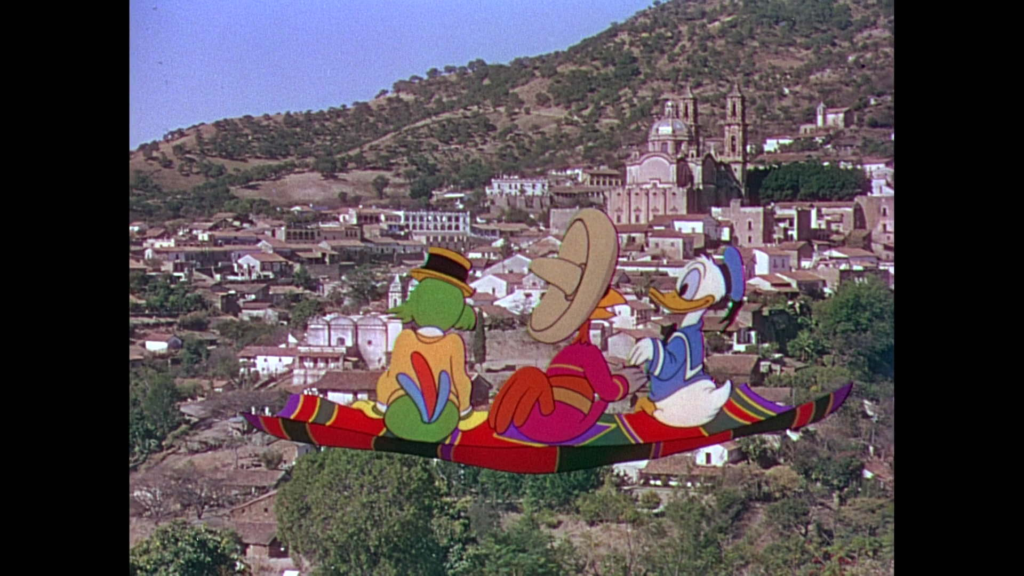

Another boring montage set to a boring song ensues, this one slightly alleviated by the influence of Mary Blair. Then the three caballeros hop aboard a magic serape and fly into the live action world of the guidebook.

Maybe if you’re interested in Mexican folk dancing, you’ll enjoy this little travel montage. I find it dull, though there is one aspect that can definitely be called interesting.

When writing about Fantasia, I argued that it represented a time when the Disney brand was less set in stone, and they could be a little more adult.[7]You could argue they’ve returned to that in recent years with the studio regularly releasing PG-13 movies, but the Disney brand still carries certain associations of fluffiness. Well, much the same can be said of The Three Caballeros where Donald is in a constant state of lust over live action women. All three of these birds are really, but especially him. Can someone more familiar with the character’s history tell me if this was always a part of his personality? It’s not so weird when it’s just Aurora Miranda, but in the Mexican section, it gets downright creepy. At one point, he drops in on a beach and starts harassing all the women. Maybe it’d be funny if they were animated or ducks, but, as it is, it’s just kind of off-putting. Jose and Panchito eventually have to drag him away.

Once outside the guidebook, Panchito turns the page to talk about Mexico City’s nightlife.

But instead of showing that, we get singer Dora Luz singing a song called You Belong to My Heart and Donald pursuing her. (See previous section.)

He searches for her through a surreal star scape, then through a surreal garden, all of which is spliced with surreal flashbacks of previous scenes. Note the frequent use of the word surreal.

Then we get Donald dancing with Carmen Molina and a bunch of cacti.

Then, without any transition,[8]Maybe one was deleted., we see Panchito having a mock bullfight with Donald as the bull. Jose lights the dynamite attached to Donald’s “tail” which explodes into a firework display. In a nice touch, we end with the words “the end” in each caballero’s native language in the colors of their respective country’s flag.

It’s hard to pinpoint why I don’t love the “trippiness” of this finale, or the movie in general, when one of my favorite Disney animated movies is the polarizing Alice in Wonderland, which is also an episodic story full of surreal visual humor. I think it’s because Alice is a better character than Donald Duck, one who responds to her surroundings with a relatable mix of appreciative wonder and increasing impatience.[9]I wouldn’t say that Donald can’t ever be relatable but he’s not here. Plus, the surreal visual humor in Alice in Wonderland is simply funnier and the songs are more consistently great.

Conclusion

Their trip across the border may have given the people at Disney inspiration in that it gave them new things to animate, but it didn’t give them many good ideas about what to animate them doing. The question with these two movies is which is the bigger waste of time. The Three Caballeros is the longer and, in that sense, the bigger waste. But it also has more flair and more genuinely fun parts. Rewatching it for the purposes of this blog, I enjoyed it more than I remembered and if I had to choose one of these two films, would probably pick it. It’s true though that the boring and even annoying parts have longer to drag in Caballeros. I can definitely understand the position that however tiresome Saludos Amigos may be, at least it’s over quickly.

Fortunately, while not all of Disney’s anim-anthologies that followed would be great, they would all be better than these South American-themed ones.

To Be Continued

References

| ↑1 | Now I’m really reminded of The Emperor’s New Groove! |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | From what I understand, the Disney company was not exactly rolling in dough when it made these movies. I’ll try to explain in the next post. |

| ↑3 | As in little burro, not the food. |

| ↑4 | Or dancing? It’s hard to say. |

| ↑5 | I assumed caballero meant cowboy but, no, it apparently means gentleman or gallant. |

| ↑6 | Wait. Mexico isn’t part of South America! |

| ↑7 | You could argue they’ve returned to that in recent years with the studio regularly releasing PG-13 movies, but the Disney brand still carries certain associations of fluffiness. |

| ↑8 | Maybe one was deleted. |

| ↑9 | I wouldn’t say that Donald can’t ever be relatable but he’s not here. |