Finally, we cut to our title character who was introduced in the opening. (That’s not a necessarily a complaint by the way. It’s not like I was desperately wondering about him or anything. Then again, that might have just been because I’d read the book before watching the movie and knew who he was. A newcomer to the story might really have gotten impatient to return to him.) Prince Caspian awakens to find himself lying in bed with his head bandaged. He’s in a room inside a tree. This is a great set, very much what I wish the beavers’ abode in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005) had looked like.

Caspian overhears a conversation in the next room. He stealthily gets out of bed, sticking close to the wall, and peeks through the door. The conversers are Nikabrik, the black dwarf played by Warwick Davis in the first scene, and a talking badger called Trufflehunter (and voiced by Ken Stott.)

Nikabrik: This bread is so stale!

Trufflehunter: I’ll just get him some soup then. He should be coming around soon.

Nikabrik: Well, I don’t think I hit him hard enough.

Trufflehunter: Nikabrik, he’s just a boy!

Nikabrik: He’s a Telmarine, not some lost puppy! You said you were going to get rid of him.

Trufflehunter: No, I said I’d take care of him. We can’t kill him now. We just bandaged his head. It-it would be like murdering a guest.

Nikabrik: Oh, and how do you think his friends are treating their guest?

Trufflehunter: Trumpkin knew what he was doing. It’s not the boy’s fault.

Of the voice actors in this film, Ken Stott gives what is easily my favorite performance, perfectly capturing the warm, wise old character from the book. The way he sadly lowers when his when speaking of his friend, Trumpkin, whom he has every reason to believe has been executed for helping Caspian, is especially great.

Speaking of Caspian, he makes a bolt for the exit, inadvertently spilling Trufflehunter’s tray of nourishment in the process. Nikabrik blocks his way and draws a sword. Caspian counters by grabbing a fireplace poker. The two of them fight despite Trufflehunter’s protests.

Nikabrik: I told you we should have killed him when we had the chance!

Trufflehunter: You know why we can’t!

Caspian: If we’re taking a vote, I’m with him.

Nikabrik: We can’t let him go! He’s seen us!

Trufflehunter: That’s enough, Nikabrik! Or do I have to sit on your head again?

That last line originates in the book though there its equivalent was said by Trumpkin who hadn’t been captured yet in that version. The same is true of the line about killing Caspian after bandaging his head being like murdering a guest. In general, while this Narnia movie is written very much in the vein of a modern action movie, I believe it has more lines that correspond to ones from the book than the last adaptation had, and I appreciate that. Nikabrik’s reaction to the line about sitting on his head is subtle but funny.

Having subdued him, Trufflehunter turns to chiding Caspian about making him spill the soup. Seeing that his life isn’t in immediate danger for the moment, Caspian takes a moment to really take in his hosts. “What are you?” he asks. “You know, it’s funny you would ask that,” says Trufflehunter, “You’d think more people would know a badger when they saw one.” Caspian clarifies that his shock comes from the fact that Narnians are supposed to be extinct. “Sorry to disappoint you,” snipes Nikabrik. Trufflehunter brings out another bowl of soup. “Since when did we open a boarding house for Telmarine soldiers?” Nikabrik grumbles. “I’m not a soldier,” says Caspian. “I am Prince Caspian the Tenth.” At these words, we hear a wistful musical theme on the soundtrack.

Nikabrik: What are you doing here?

Caspian: Running away. My uncle has always wanted my throne. I suppose I have only lived this long because he did not have an heir of his own.

Trufflehunter: That changes things.

Nikabrik: Yeah, it means we don’t have to kill you ourselves.

Caspian: You are right.

This scene contains the first really long lines from Caspian so I should take a moment here to stop and say something about his “Telmarine” accent. Ben Barnes didn’t have as much time as might be wished to practice it and many viewers, including some who are fans of the film on the whole, find it cheesy. Me, I don’t mind it, but enough people do that I feel I should acknowledge their opinion. Anyway, Caspian put on his chainmail and prepares to leave. “Where are you going?” asks Trufflehunter. “My uncle won’t stop until I’m dead,” replies Caspian, apparently having decided to go back and confront Miraz and maybe get some support from some of the Telmarine nobles we saw a few scenes ago. We’ve now come to a change from the book’s story and protagonist that in this fan’s opinion, really hurt the movie. In the original version, Caspian has no wish to leave Trumpkin, Trufflehunter and Nikabrik once he meets them. He’s grown up hearing stories about what the book calls “Old Narnians” and is utterly delighted to have met some of them even though at least one of them wishes to kill him. Basically, Caspian is a big Narnia nerd/fanboy. That is the main thing that makes him interesting or endearing in the book. In this movie, while he’s not opposed to the Old Narnians the way his uncle is, we really don’t get that smitten fanboy vibe at all. Not only does this make him less distinctive of a character but it means lessening, even losing, the book’s theme of longing for something beyond the mundane world. But maybe it’s too early to lament that. I hope to write more about it in next week’s post. “You can’t leave,” Trufflehunter protests. “You’re meant to save us!” He holds up the horn Caspian blew. “Don’t you know what this is?”

Again, the movie cuts to another scene right when a character is going to explain about the horn! This really is frustrating by now but don’t worry. This next scene actually will explain everything or near enough.

Back at the Telmarine castle, Dr. Cornelius returns to his study[1]Another great set. to find that the door is ajar, which isn’t how he left it. He enters to find Miraz casually reading a book. “You have quite a library, doctor,” he says. “Is there anything particular you seek, my lord?” asks Cornelius. “I think I’ve already found what I’m looking for,” says Miraz, “in one my soldiers!” And he stabs a book with Susan’s arrow. To be more specific, he stabs it into an illustration of King Peter, Queen Susan, King Edmund and Queen Lucy. This is probably the craziest instance of the characters being able to identify the Pevensies’ Christmas gifts centuries later. Peter’s sword I can maybe buy. But are arrows with the feathers dyed red really that rare in this world? To be fair though, the fact that Trumpkin’s mysterious rescuers appeared near the ruins of Cair Paravel makes this a bit more plausible. It would have been less of a logical leap if they had established that the movie’s Telmarines feared ghosts in that area as the ones in the book do.

Anyway, as Cornelius looks at the illustration, we hear the musical theme associated with the Pevensies at their most heroic from the last movie.

Miraz: What do you know of Queen Susan’s horn?

Cornelius (carefully): It was said to be magic.

Miraz: Magic?

Cornelius: The Narnians believed it could summon their kings and queens of old. At least, such was the superstition.

Miraz: And what does Caspian know of this…superstition?

Cornelius: My lord, you forbade me from mentioning the old tales.

Miraz: So I did.

That last part is a reference to something from Caspian’s childhood in the book that tragically isn’t in the movie. Dr. Cornelius turns to see soldiers ready to arrest him and decides to go down defiantly. “I will say this,” he says, looking Miraz in the eye for what feels like the first time in the scene, “If Caspian does know of the deep magic, my lord would have good reason to be nervous.” In the book at this point, by the way, Dr. Cornelius, who is “a very minor magician,” makes himself scarce, “having no wish to be questioned… in Miraz’s torture chamber” and actually manages to escape and find Caspian. I mention that as an observation by the way, not a criticism.[2]Though, on reflection, I understand why some fans of the character might object to making him less competent. I also don’t mind taking away the character’s magician status. After all, the only magic he did in the book was drugging Caspian’s gentlemen-in-waiting so he could escape and later magically tracking him to Dancing Lawn.

In the hallway, Sopespian sees Dr. Cornelius being led away and takes the opportunity to try to win Glozelle to his side.

Sopespian: First our prince, now his tutor. If the members of Miraz’s own house are not safe, are any of us?

Miraz (offscreen): Lord Sopespian!

Glozelle: Those are dangerous words, Lord Sopespian.

Sopespian: But these are dangerous times, General. One should choose his words as carefully as he chooses his friends.

In the study, Miraz asks Sopespian how long until “the bridge” is finished. (We’ll see what he means before too long.) “Construction continues on schedule,” Sopespian replies. “That’s not good enough,” says Miraz. “I need my army across that river now!” Sopespian suggests Miraz contribute some of his own men. “I have only so many at my disposal,” he says. “A fact you’d be wise to remember,” Miraz snarls. He turns to Glozelle. “Go to Beruna. Take as many troops as you need. We must get to Caspian before they do.” Sopespian asks whom he means by “they.” “It’s time you learned your history,” says Miraz and storms out of the room. Left alone, Sopespian looks at Susan’s arrow sticking out the book about her. That might not seem like it could possibly be important now but trust me.

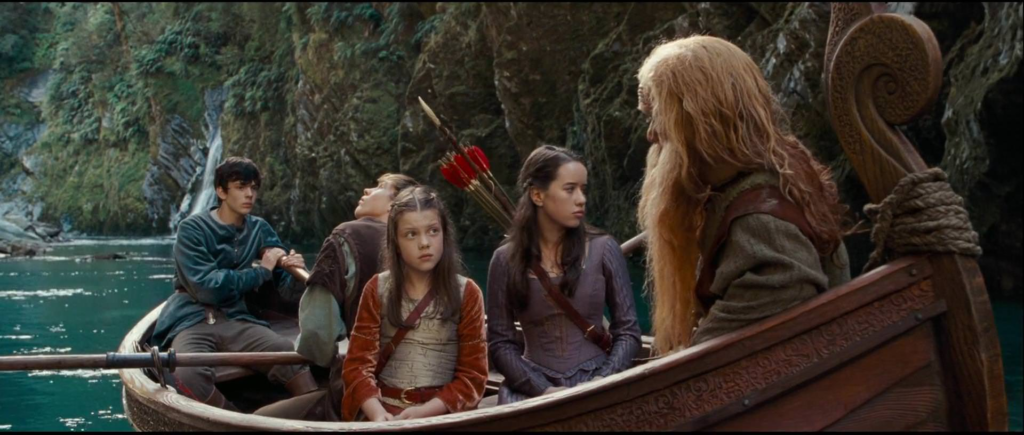

Meanwhile, the Pevensies and Trumpkin are rowing inland into Narnia in the boat they got from Trumpkin’s would-be executioners. The scenery is beautiful, but the returning monarchs don’t seem to be enjoying it much.

Lucy: They’re so still.

Trumpkin: They’re trees. What’d you expect?

Lucy: They used to dance.

Trumpkin: It wasn’t long after you left that the Telmarines invaded. Those who survived retreated to the woods. The trees…they retreated so deep into themselves that they haven’t been heard from since.[3]This makes the trees’ comatose state sound more self-imposed than in the book which describes the Telmarines as silencing them.

Lucy: I don’t understand. How could Aslan have let this happen?

Trumpkin: Aslan? I thought he abandoned us when you lot did.

There’s a lot to unpack here. A minor thing this adaptation specifies that the book doesn’t is that Caspian’s ancestors conquered Narnia fairly soon after Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy returned to their own world.[4]According to a timeline C. S. Lewis wrote, which was published after his death, it was actually nine-hundred and eighty-three years later. But there are some things in the timeline that don’t … Continue reading This gives the Pevensies more reason to feel guilty for not being there to defend their kingdom.[5]You could argue they’re responsible however much time passed between their absence and the Telmarines’ invasion since if they had left heirs behind, Narnia might very well have been in a … Continue reading I’ve described this movie previously as packing a bit more of an emotional punch than the book does-or trying to do so anyway. This is one of the reasons why. Another reason is that in the book, this exposition comes from Dr. Cornelius telling it to the young Caspian who has only heard of dryads and naiads in bedtime stories. We never see the Pevensies’ initial reaction to learning how much Narnia has lost. It probably isn’t quite as sad as the movie wants it to be, mainly because we haven’t seen enough of the trees being alive in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe for the contrast to really stand out here.

But that’s a complaint that could be made against the books too[6]C. S. Lewis, or, more specifically, his characters told us that the trees were listening in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe far more often than he ever showed us evidence of it. and it’s still pretty sad. Georgie Henley’s line readings and Peter Dinklage’s pained facial expressions are very effective.

A side effect of having Trumpkin be the one to give this exposition though is that he has to believe in dryads, the ancient kings and queens of Narnia’s golden age, and Aslan. In the book, he believes in things like dwarfs, fauns, centaurs and talking beasts because, well, he’s one of them and he’s seen them all his life. But he is inclined to agree with the Telmarines’-or the Telmarines’ official story that other parts of Narnia’s past never existed. Note that he says Aslan and the Pevensies abandoned his people, implying that they exist. Whether intentionally or not, this conveniently allows the movie to resonate with theists, specifically Christians, who struggle with the feeling that God has abandoned them without necessarily alienating atheists.[7]For what it’s worth, the honestly skeptical Trumpkin was more positively portrayed by the book than Nikabrik who says he’ll “believe in anyone or anything that’ll batter these … Continue reading I feel like this makes the world of the story less rich as there are fewer worldviews represented in it. In the book, we get Miraz who denies the entire existence of “Old Narnia,” Trufflehunter, Caspian and Cornelius who believe in all of it and Trumpkin who believes in the parts he can confirm to be true but only them. In the movie, we get a background character who refers to Narnians as fairy tales but otherwise, everyone, good or bad, agrees about the truth of the old stories. They just disagree about whether or not the legendary figures in them can be trusted. To be fair, that’s still an interesting question to explore.

Peter is stung by Trumpkin’s last comment. “We didn’t mean to leave, you know,” he says. “Makes no difference now,” says Trumpkin. “Get us to the Narnians and it will,” Peter insists, quickening his oar strokes. This implied guilt goes some way to keeping the movie’s reimagining of Peter from being totally unsympathetic, but it doesn’t go as far might be wished. Later, the crew pulls up onto the shore. While the others secure the boat, Lucy wanders a little way away from them and sees a bear. “Hello there,” she calls, assuming it can talk. The bear rises on its hind legs, threateningly. “It’s alright,” says Lucy, “we’re friends. Her older siblings see this and aren’t particularly concerned but Trumpkin stiffens in horror. “Don’t move, Your Majesty,” he calls. Lucy automatically turns toward him and the bear charges at her, growling. Susan draws her bow. “Stay away from her!” she cries. But the beast pays her no heed. Before it can hurt Lucy, an arrow brings the bear down but it’s Trumpkin’s arrow, not Susan’s. “Why wouldn’t he stop?” she asks. “I expect he was hungry,” Trumpkin replies.

Lucy thanks Trumpkin for saving her. It’s a brief moment but it serves to show them bonding. She and her brothers and sisters stare at the bear’s body. “He was wild,” says Edmund. “I don’t think he could talk at all,” says Peter. “Get treated like a dumb animal long enough, that’s what you become,” says Trumpkin, taking out a knife and starting to skin the bear. “You may find Narnia a more savage place than you remember.”

What I find interesting about this scene is that fans of the Narnia books who dislike the movie adaptations typically criticize them for adding random action scenes.[8]If you’re someone who likes the books and not the movies and you feel like I’m stereotyping, I beg your pardon. But this bear attack pretty much was a random action scene in the literary Prince Caspian where its main function was to give the heroes something to eat besides apples. This adaptation gives it much more of a point.[9]While still having it serve to provide the characters with bear meat. The book had already established that talking beasts had become the exception rather than the rule in Narnia by this point. The movie hasn’t and this bear’s animal behavior is meant to be a shock both to the Pevensies and to the viewers. Again, I don’t think it totally works. If it did, we would empathize more with Lucy’s reaction to the bear, but I feel like she and her siblings just come across as silly. Maybe the problem is that while we’ve seen plenty of talking animals in Narnia before this point, with the major exception of Aslan, they’ve been relatively small.[10]I believe there was a presumably talking bear in Aslan’s army in the last movie, but he was just in the background. This scene kind of gives the impression there were no dumb beasts in Narnia at all when the Pevensies reigned, which raises some questions, the main one being what did they do for meat then? The Narnia books are a lot more specific about how all this works. The question can be resolved though by the idea that all the bears in Narnia originally talked but other species had both talking and nontalking examples.

Anyway, while I don’t think the scene is as emotionally devastating as the movie intended it to be, the idea behind it was solid and it’s still somewhat emotionally devastating. I especially like the way Lucy weeps into Peter’s shoulder at the end of the scene. Hmm, I hope that last sentence didn’t sound too sadistic.

I Think I’ll Take a Break From Blogging Next Week. But the Following Week, We’ll Meet One of the Most Memorable Narnian Supporting Characters

References

| ↑1 | Another great set. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Though, on reflection, I understand why some fans of the character might object to making him less competent. |

| ↑3 | This makes the trees’ comatose state sound more self-imposed than in the book which describes the Telmarines as silencing them. |

| ↑4 | According to a timeline C. S. Lewis wrote, which was published after his death, it was actually nine-hundred and eighty-three years later. But there are some things in the timeline that don’t quite align with the books, so it’s debatable if fans should accept it as canon. |

| ↑5 | You could argue they’re responsible however much time passed between their absence and the Telmarines’ invasion since if they had left heirs behind, Narnia might very well have been in a better condition to defend itself. |

| ↑6 | C. S. Lewis, or, more specifically, his characters told us that the trees were listening in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe far more often than he ever showed us evidence of it. |

| ↑7 | For what it’s worth, the honestly skeptical Trumpkin was more positively portrayed by the book than Nikabrik who says he’ll “believe in anyone or anything that’ll batter these cursed Telmarine barbarians to pieces.” |

| ↑8 | If you’re someone who likes the books and not the movies and you feel like I’m stereotyping, I beg your pardon. |

| ↑9 | While still having it serve to provide the characters with bear meat. |

| ↑10 | I believe there was a presumably talking bear in Aslan’s army in the last movie, but he was just in the background. |