Charles Dickens’ third novel, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, is one of my favorites though that’s not a universally held opinion. Many critics, while commending the book’s youthful energy, deride its stock characterizations and meandering, melodramatic plot. I adore it, in large part, because of those very things. This book contains just about everything that makes Dickens so much fun. Underdog heroes. Not one, but two ruthless old misers. Two saintly, longsuffering heroines, one of whom is devoted to her unappreciative father. Two or three merry, generous old gentlemen. One merry, generous old woman. A lot of kooky, flamboyant supporting characters. Satirical depiction of child abuse. Dramatic revelations about parentage. Amazing coincidences. A tearjerking deathbed scene. Good rewarded. Evil punished. All it needs is an angelic child, preferably an orphan who dies tragically, to be the ultimate Dickensian thrill ride. It’s also one of the funniest things he wrote, much funnier, in my opinion, than the more consistently comedic Pickwick Papers. And for those who prefer their classics to be “relevant,” this one’s theme of sexual harassment gives it a special interest for modern readers.

As much as I love it though, I’m not going to look at all of the filmed adaptations in this series. There are too many of them for that and not all of them are readily available to watch. I’m just going to write about the four that have endeared themselves to me the most. Please note that I’m going through them in the order they were released. While I know which one I consider the best, it gets harder for me to rank them after that, so this is the most practical. With no further ado…

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1947)

Like the book, this film from French-Brazilian director Alberto Cavalcanti tells the story of a young country gentleman, Nicholas Nickleby (Derek Bond) whose father dies, having lost his money through bad investments. Nicholas, his mother (Mary Merrall), and sister, Kate (Sally Ann Howes) are forced to turn for help to said father’s brother, Ralph (Cedric Hardwicke), a ruthless moneylender in London, whom they have never met. Ralph pulls some strings to get Nicholas a job working at Dotheboys Hall (pronounced do-the-boys), a boarding school in Yorkshire run by Wackford Squeers (Alfred Drayton.) Nicholas soon finds the school is a miserable place where parents send embarrassing sons whom they never want to see again who are abused by Squeers and his wife (Sybil Thorndike.) He befriends a pathetic, mentally crippled young man called Smike (Aubrey Woods) who has been left at the school for most of his life. Nicholas and Smike end up fleeing Dotheboys Hall together and Nicholas searches for a way to support himself and his family without his uncle’s help.

Naturally, the plot of the seven-hundred-plus page novel is simplified and reconstructed for the under-two-hour film. While Ralph Nickleby’s fellow evil moneylender, Arthur Gride (Lawrence Hanray) appears, he mainly serves as a device to allow Ralph to give exposition about his plans. It’s Ralph himself who takes over his actions. [1]Gride is the character most likely to be combined with another in Nicholas Nickleby adaptations. While he plays a major part in the story, he’s introduced very late, and it makes sense to have … Continue reading More problematically for me as a fan, Ralph’s clerk who aids Nicholas, Newman Noggs (Bernard Miles, whom Dickens fans may remember as Joe Gargery in the 1946 Great Expectations movie)[2]They may also recognize James Hayter, who here plays both Cheeryble brothers as the lead in the 1952 Pickwick Papers movie. is combined with Brooker, another character with a vendetta against Ralph. This makes him much darker and less likeable than in the book.

Generally, though John Dighton’s screenplay stays very true to its source. Well…sort of. While the story and most of the characters are faithful to what Dickens wrote, the dialogue, for the main characters anyway, tends to be original. Some may consider this an improvement as the dialogue Dickens wrote for Nicholas Nickleby tended to be very florid and artificial. But as a big Dickens fan, I cannot agree with this. However, there have been enough adaptations that did try to include a lot of the original dialogue or at least keep the spirit of it that I don’t mind this one doing something a bit different. I imagine a lot of the reasoning behind it was to fit as much as possible into the runtime, which would have been hard with so many big hammy speeches. And the script certainly isn’t badly written.

The villainous and the comedic characters, two categories that overlap but are not interchangeable, tend to get more of their memorable lines from the book than the heroes do, or at least work in their catchphrases. With them though the movie almost feels like it’s trying too hard to be true to the book. Mr. and Mdme. Mantalini (Cyril Fletcher and Fay Compton), who at one point employ Kate Nickleby, Miss Knag (Cathleen Nesbitt), who also works for them, Mr. Gregsbury MP (Michael Shepley), the politician to whom Nicholas applies for the position of secretary, the Kenwigs family for whom he (Nicholas) briefly serves as a tutor, and Mr. Lillyvick (John Salew), their self-important uncle, are all given a ridiculous amount of characterization considering they each appear for one scene, making it very obvious that this film has been adapted from something much longer.[3]Gregsbury only has one scene in the book too, but it’s a longer scene. In particular, Mr. Lillyvick’s cameo gives new meaning to the word, gratuitous.

On the other hand, Miss La Creevy (Athene Seyler), the Nicklebys’ friendly landlady, who is actually one of my favorite characters in the book despite not doing much, and her love interest, the irascible Tim Linkinwater (Roddy Hughes, Fezziwig in the 1951 Scrooge), get a great deal of screentime, but don’t really show any personality beyond being amiable. John Browdie, the hearty Yorkshireman, another of my favorite characters, only gets a brief allusion and doesn’t appear at all. I know it’s hypocritical of me to first criticize this adaptation for including characters without developing them and then complain about it cutting others for time, but it’s hard not to do that when discussing Nicholas Nickleby adaptations! The only comedic figure, besides Squeers, who feels like he’s given neither more nor less screentime than he needs is Vincent Crummles (Stanley Holloway), the theater manager with whom Nicholas and Smike fall in for a time.

Ah, Crummles! He could easily be written out of the story, but he and his troupe are so much fun that no adaptation, however short, does so.

While the movie clearly bites off more than it can chew, as a fan of the material, I can’t blame it for wanting a big bite. The bit characters of Nicholas Nickleby are all so vivid and so much fun; speaking more as a Dickens lover and less as objective analyst, I enjoyed every pointless cameo. And some characters are arguably better developed than they were in the book, mainly Frank Cheeryble (Emrys Jones) whose romance with Kate was entirely implied in the novel. And Nicholas’s love interest, Madeline Bray (Jill Balcon), exchanges some dialogue with him in the (relatively) early scene in which she’s introduced. We then follow her and her father (George Relph)’s story alongside that of the other characters rather than having it all explained when she and Nicholas reconnect in the last act.

The sets, costumes and, for the most part, the look of the actors are quite reminiscent of the original illustrations by Hablot K. Browne, giving this a vintage Dickensian feel. Apart from their looks, everyone in the cast is at least good and some of them great. Jill Balcon is one of the most striking Madeline Brays I’ve seen, and Mary Merrall gives my favorite performance as Nicholas and Kate’s garrulous, self-absorbed mother bar none.

Despite the unfortunate, inevitable cramming, many of the book’s most memorable dramatic moments are done effectively. The primal appeal of the story is very much in evidence. (The conflict basically boils down to good looking poor heroes vs. ugly rich villains. You don’t get much more primal than that.)

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1982)

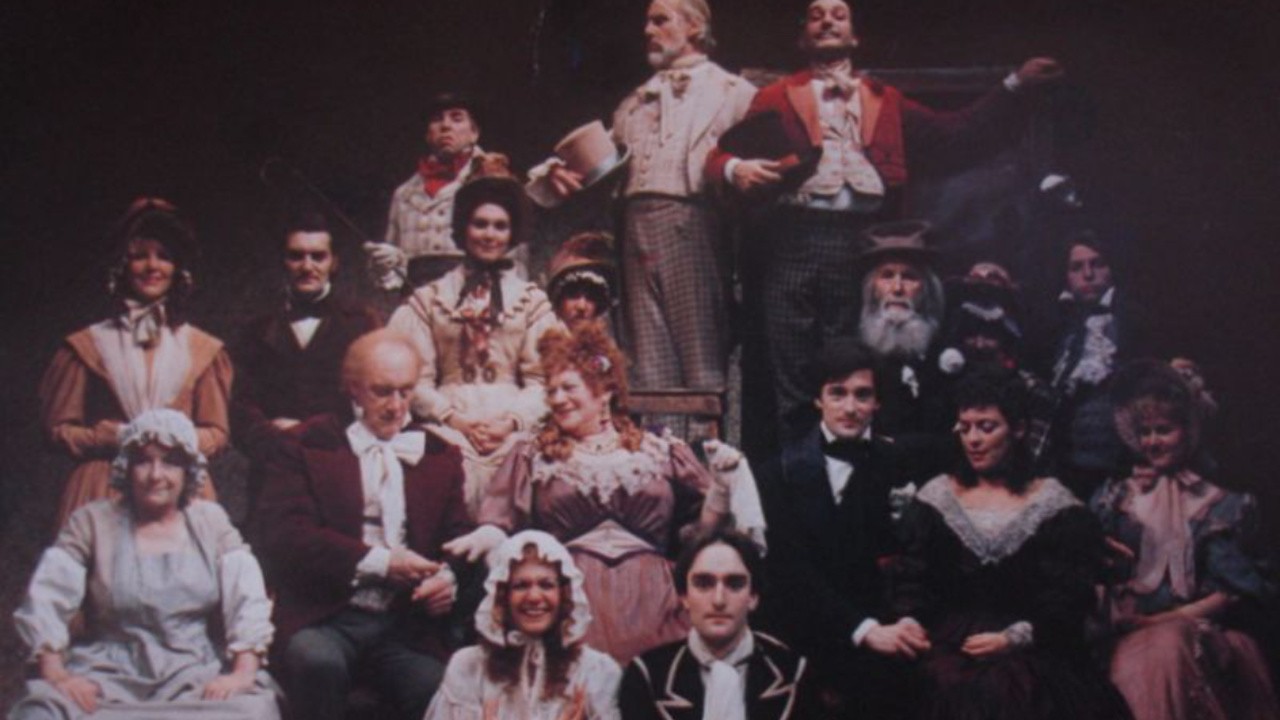

In 1980, the Royal Shakespeare Company did an eight-hour play adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby written by David Edgar and directed by Trevor Nunn and John Caird. [4]The latter two would later collaborate on another adaptation of a classic novel, the original West End version of Les Misérables. In 1982, a version was filmed for television. While this performance was filmed without an audience, the better to do multiple takes, footage of one from a regular showing is intercut. We mainly see them applauding when one of the baddies is getting some comeuppance. It’s interesting to see which parts they (apparently) responded to the most enthusiastically, but it’s rather distracting. After one of their reaction shots, I’d find myself wondering for several scenes why no one was laughing or coughing or anything. And by the time I’d gotten used to the audience’s absence, they would suddenly appear on screen, taking me out of the experience. Perhaps Jim Goddard, who directed this for television, felt that with so many instances of the actors walking down the aisle or into the audience, it would be odd to see so many empty seats. I’m not convinced that wouldn’t have been the lesser of two evils, but I guess I can understand it.

Anyway, this is easily the most complete adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby I’ve seen.[5]Some of the miniseries I haven’t seen may be more complete. It must be the only to retain the public meeting from Chapter II of the book about the United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company. The subplots of the Mantalinis and the Kenwigses, which barely connect to the main story, are included and fully developed.[6]The original stage production also included the hilarious subplot of the Nicklebys crazy next-door neighbor, who woos Mrs. Nickleby, though it’s sadly been cut here. On the plus side, a … Continue reading Yet the play never feels as slow paced as the book does.[7]That’s not a knock on the book. Slow pacing can have benefits. I just don’t believe the book’s pacing would work in many other mediums. The character arc for Lord Frederick Verisopht (Nicholas Gecks), one of Ralph Nickleby (John Woodvine)’s clients who stalks Kate (Emily Richard), is also better developed than in any other adaptation. In some, like the 1947 movie[8]Or the 2001 miniseries that didn’t make my top four, his redemption comes out of nowhere. In the 2002 movie, on the other hand, it’s obvious from the start that he’s better than the others in his peer group and it’s not very interesting to see him redeemed. Not so here.

At the same time, this is hardly a cut-and-paste adaptation. The order of events is shrewdly rearranged. Different scenes are combined with each other and so are two inconsequential but memorable pompous politician characters, Sir. Matthew Pupker (David Lloyd Meredith) and Mr. Gregsbury. The Cheeryble brothers (Meredith again and Hubert Rees) explaining their benevolent scheme for Madeline Bray (Lucy Gutteridge) to Nicholas (Roger Rees) is done as a split scene with Arthur Gride (Jeffery Dench) explaining his not so benevolent one to Ralph. As should come to no surprise to those familiar with Trevor Nunn, the tragic side of comedic characters, like Madame Mantalini (Thelma Whitley), Miss Snevellici (Suzanne Bertish) and Mr. Lillyvick (Timothy Kightley), is emphasized mostly to good effect in this case. Along opposite lines, the character of Fanny Squeers (Bertish again) is allowed more of the possibility of redemption and her uneasy friendship with the catty Tilda Price (Cathryn Harrison) ends on a more positive note. It’s rare for me to say that any adaptation improves on Dickens, but the halting way in which this Smike (David Threlfall) speaks as if every word were a struggle for him is more heart-wrenching and does a better job of conveying his mental disability than the book where he speaks as eloquently as everyone else.

The main reason the Royal Shakespeare Company decided to tackle this particular Dickens novel in so lavish a fashion[9]besides that the ones they preferred were already being staged by others was Crummles (Christopher Benjamin)’s hilarious troupe of actors, and they’re the center of one of this adaptation’s most inspired original ideas: their staging of Romeo and Juliet, the ending of which we see in detail. However, it’s also the most niche part of the play. To fully appreciate it, you have to be familiar with Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare’s plays in general and how some of his tragedies were adapted for English Victorian audiences.[10]I know the last one from studying King Lear in high school. It’s definitely comedy for theatre people by theatre people. On that level it works and Romeo and Juliet is famous enough that the broad joke should be understandable to most people. Lines from the play are also recalled in a climactic scene to great emotional effect. Preparations for Ralph’s dinner party are also cleverly interwoven with the troupe’s rehearsal, so that dialogue from the latter serves as a commentary on the former. While I’m cynical about why so many Shakespeare allusions are included in this play, they all work.

This adaptation also does the best job of updating the heroines without making it feel like people from a modern story have been randomly inserted into a Victorian one. This is mainly done by having them faint less and give more defiant speeches, transferring a number of Nicholas’s angry lines to Kate.[11]I’d argue she, unlike Madeline, didn’t really need that much updating. The play does miss a trick though. In the book, when Kate asks Ralph to tell his business clients to stop harassing her and he refuses, she says that she and her mother cannot accept his charity then and are going to leave the house he’s given them as soon as possible. Here, she just says, “Uncle, you have been selling me!” and runs out of the room, crying.

You’re probably thinking, “Wow, Stationmaster, this sounds like your favorite Nicholas Nickleby adaptation!” Well…no. It’s true that it’s one of the most complete and thoughtful as far as the plot goes, but I’m not always a fan of how it adapts the dialogue. I understand that it would be impossible to fit so many plotlines into nine hours without some trimming, but it seems a shame to cut Ralph’s response to Mrs. Nickleby (Jane Downs)’s lament that the death of her husband was “no common loss.” “It was no uncommon loss, Ma’am. Husbands die every day…” That brief exchange perfectly captures both their characters. It’s hard for me to imagine an adapter not wanting to include it somehow or other. Another example is the dialogue about Mrs. Crummles (Lila Kaye) being “the original blood drinker” onstage. Here’s how it goes in the book.

“Was she indeed?”

“Yes. She was obliged to give it up though.”

“Did it disagree with her?” asked Nicholas.

“Not so much with her, as with her audiences,” replied Mr. Crummles. “Nobody could stand it. It was too tremendous.”

And here’s how it is in the play.

Nicholas: No, I didn’t know that. No.

Mrs. Crummles: Yes, I was obliged to give it up, however.

Nicholas: Oh, I’m sorry. Why was that, Ma’am?

Mrs. Crummles: Oh, the audiences, sir. They couldn’t stand it. It was too tremendous.

Did they really have to change or cut the funniest bits there? And from the perspective of newcomers to the story, the exposition isn’t always as clear as might be wished.

More damningly, I don’t really like Roger Rees as Nicholas. I understand that it would be impossible to have an actual nineteen-year-old in such a big role and that actors being older than their characters is a common theatrical convention. But I first discovered Nicholas Nickleby when I was eighteen myself, and part of its appeal for me was the hero being a normal guy around my age who went around standing up for his convictions, saving people in need, supporting his family and beating up bullies. It’s important to me that he come across as a quite young adult. Roger Rees in 1982 wasn’t exactly Mr. Lenville,[12]Read the book to get that joke. but he neither looks nor feels young here. For the record, I have less of a problem with Emily Richard’s Kate, even though she’s supposed to be even younger, which leads me to think he just wasn’t a great choice for the part.

![100 television stage plays: [8] 1982-1990 | SCREEN PLAYS](https://screenplaystv.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/snapz-pro-xscreensnapz0011.jpg)

Other than that, all the actors do a fine job though I don’t find many of them to be great in their roles-or, more accurately, with so many actors, out of necessity, playing double or triple roles, and some of them doing a better job of disguising themselves than others, I find them to be great in some of their roles but not all of them. For example, Bob Peck is great as Sir. Mulberry Hawk, the dissipated rake who persecutes Kate, but just OK as John Browdie. And Lila Kaye is simply one of many great Mrs. Squeerses, but she’s the best Mrs. Crummles ever. Besides her, the only character portrayals here to be the best of any adaptation are John Woodvine’s steely Ralph and Edward Petherbridge’s seemingly pathetic, secretly crafty Newman Noggs. David Threlfall as Smike deserves praises for sheer commitment, contorting his face and body language every second he’s onstage, even going so far as to drool in one scene.

Rather than having a single actor be the narrator, the entire company adresses the audience and provides narration, with even the actors who are the central focus of a scene stepping out of character to describe themselves in third person, though they (sort of) retain their personas for comedic or dramatic effect. It’s very theatrical and I don’t want to criticize a stage play for doing something that only a stage play could do. Actually, I highly approve of this one’s use of soliloquies which allow it to get inside Ralph’s head in a way that the book does, but most adaptations can’t. And the ensemble narration leads to one of this Nicholas Nickleby‘s most powerful moments, a shortened version of the passage from Chapter LIII of the book about “how much injustice, misery and wrong there was, and yet how the world rolled on, from year to year alike, careless and indifferent.” I suppose if I were a “real fan” of the play, it would be part of the appeal. But it means that the audience is very aware of the play as a performance and I can’t really get lost in a world when I watch it, the way I do with the source material or most other adaptations.[13]The fact that the same actors play the background characters in every location, meaning that the boys at Dotheboys Hall are all adults, at least one of them a woman, and at least one of the women … Continue reading There are also a few instances, thankfully not too many, where the narration strikes me as really gratuitous. We don’t need to have Nicholas the narrator tell the audience that he “looked out the window and sighed.” The actor could just look out the window and sigh.

My biggest beef with this adaptation actually has to do with the very last scene. While Dickens’s endings typically reward most of the good characters and punish most of the bad ones, he semi-frequently has the last paragraph, or at least the second-to-last one, be about someone we like who has died at some point in the story, reminding us that life isn’t always so fair for everyone. It’s great that this play picked up on that but what they do strikes me as not just balancing out the overall happy ending with sadness but overwhelming, even subverting it. The final tableau implies that the terrible things he’s witnessed will prevent Nicholas from ever being completely happy, which isn’t the impression given by the book. [14]Since David Edgar was a Marxist and I’m anti-Marxist in my thinking, I’m tempted to blame all the things I don’t like about this play on his views. But that would be irrational and … Continue reading

While all this keeps the play/TV serial from being the ultimate adaptation it feels like it should have been, every fan of Nicholas Nickleby, or Dickens in general, should see it at least once.

To Be Continued

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. (2011). The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. London, UK: Arcturus Publishing Limited.

Edgar, David. (1982). The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. New York: Nelson Doubleday, Inc.

References

| ↑1 | Gride is the character most likely to be combined with another in Nicholas Nickleby adaptations. While he plays a major part in the story, he’s introduced very late, and it makes sense to have someone else fulfill his role. It’s also possible adapters consider him uncomfortably similar to the stereotypical evil, groveling, moneygrubbing Jewish moneylender. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | They may also recognize James Hayter, who here plays both Cheeryble brothers as the lead in the 1952 Pickwick Papers movie. |

| ↑3 | Gregsbury only has one scene in the book too, but it’s a longer scene. |

| ↑4 | The latter two would later collaborate on another adaptation of a classic novel, the original West End version of Les Misérables. |

| ↑5 | Some of the miniseries I haven’t seen may be more complete. |

| ↑6 | The original stage production also included the hilarious subplot of the Nicklebys crazy next-door neighbor, who woos Mrs. Nickleby, though it’s sadly been cut here. On the plus side, a hilarious description of the conflicting demands of rising actress Miss Snevellici’s patrons, which was apparently not in the original production, judging by the published script, is included here. |

| ↑7 | That’s not a knock on the book. Slow pacing can have benefits. I just don’t believe the book’s pacing would work in many other mediums. |

| ↑8 | Or the 2001 miniseries that didn’t make my top four |

| ↑9 | besides that the ones they preferred were already being staged by others |

| ↑10 | I know the last one from studying King Lear in high school. |

| ↑11 | I’d argue she, unlike Madeline, didn’t really need that much updating. |

| ↑12 | Read the book to get that joke. |

| ↑13 | The fact that the same actors play the background characters in every location, meaning that the boys at Dotheboys Hall are all adults, at least one of them a woman, and at least one of the women working at Mdme. Mantalini’s is a guy, also does this, though that’s basically inevitable, so I don’t want to complain about it too much. |

| ↑14 | Since David Edgar was a Marxist and I’m anti-Marxist in my thinking, I’m tempted to blame all the things I don’t like about this play on his views. But that would be irrational and unfair, especially since this adaptation weirdly goes out its way not to be Marxist in the end, stressing that some of the characters are rich and that doesn’t make them bad people. |