Peanuts is awesome. Not only does it have a unique and extremely funny sense of humor, but its characters and images are like mythic archetypes that sum up aspects of the human experience. Do Sisyphus and his boulder represent the inevitability of failure better than Charlie Brown and Lucy’s football? Does Viola’s speech in Twelfth Night about “Patience on a monument” describe the pain of unrequited love, unexpressed unrequited love in particular, better than the little red-haired girl? Besides the comic strip itself, Peanuts has provided us with countless animated specials.[1]Well, OK, they’re not literally countless. You can count them but it’s intimidating. But you’re likely only familiar with three of them[2]If you’re American anyway. If you’re from another country, you may not even be familiar with those., A Charlie Brown Christmas, It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown and A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving. And there’s a school of criticism that claims the last one of those is inferior to the other two.[3]I, myself, sometimes think It’s the Great Pumpkin is a little overrated but that’s not worth a fight.

But is it true that there are only two or three truly great Charlie Brown specials? I say nay! And I am going to write about the ones that I think are the most underrated.[4]I’m actually doing this as both a YouTube video and a blog post. If you’d like to watch the video version (and check out of my extremely modest YouTube channel), here it is, but I warn … Continue reading

Charlie Brown’s All Stars (1966)

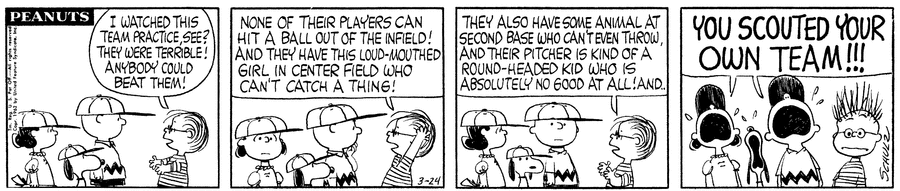

This one has a particularly good vintage, coming out right between A Charlie Brown Christmas and It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown but, not being associated with a holiday, it hasn’t gotten the same amount of airtime. Just as It’s the Great Pumpkin adapted a number of great Halloween-themed Peanuts comics, this one adapts a number of great baseball-themed ones and just as A Charlie Brown Christmas featured a dramatically compelling original story, so does this.

Charlie Brown (voiced by Peter Robbins)’s team has finally had their fill of losing and quits, but he’s able to lure them back when local department store owner, Mr. Hansen, offers to be their sponsor and provide them with uniforms. (Like the average adult in a Peanuts special, Mr. Hansen is never seen, and his voice is represented by a foghorn-like sound effect.) But then Charlie Brown has to turn down the offer for a good reason, but one which he can’t explain to his team without hurting them. This leads to a pretty devastating scene, but a happy ending is reached-only to be undermined in typically humorous Peanuts fashion.

Play It Again, Charlie Brown (1971)

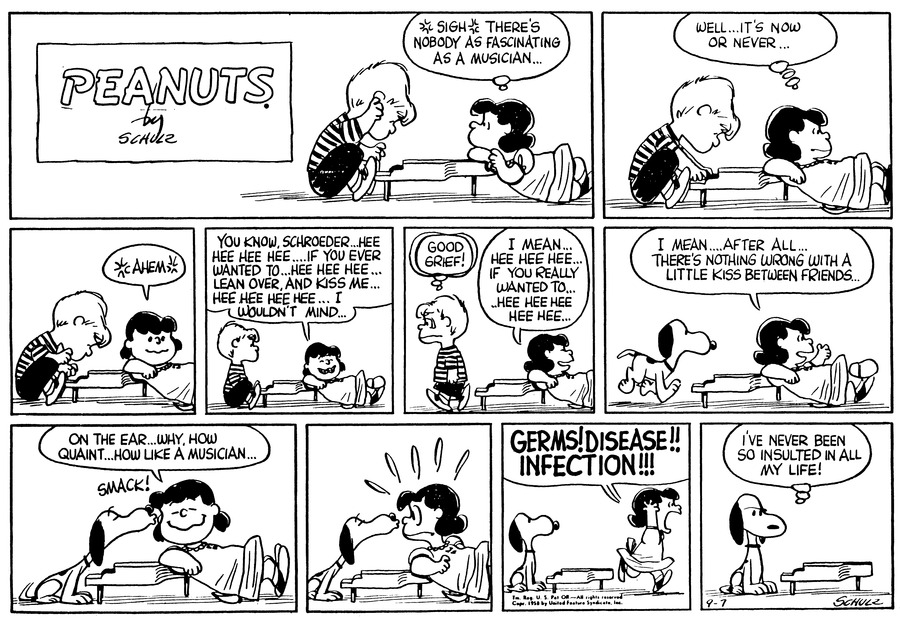

Pamelyn Ferdin was probably the best voice actress who ever portrayed Lucy. She could bring out the character’s vulnerable sensitive side while still sounding as brash as she should. This special focuses on her hopeless love for Schroeder (Danny Hjeim) and makes the most hated member of the franchise’s cast quite sympathetic. In the final act, after several hopeless attempts at gaining the miniature musical prodigy’s affections, she manages to get Schroeder the opportunity to play in front of a large audience. Unfortunately, it requires him to play music besides Beethoven and Schroeder has to decide whether or not to compromise his artistic principles. (His reaction to Lucy’s assumption that his piano needs to be plugged into an amplifier is a scream. Literally.)

This conflict does create a continuity problem with A Charlie Brown Christmas and It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown where Schroeder seemed perfectly happy to play the works of Vince Guaraldi, John McCormack and others. There’s arguably a callback in the dialogue to the first special, so it’s not as if they’re taking place in separate continuities. But if you’re willing to ignore that little hiccup, this is one of the most interesting Peanuts specials.

You’re Not Elected, Charlie Brown (1972)

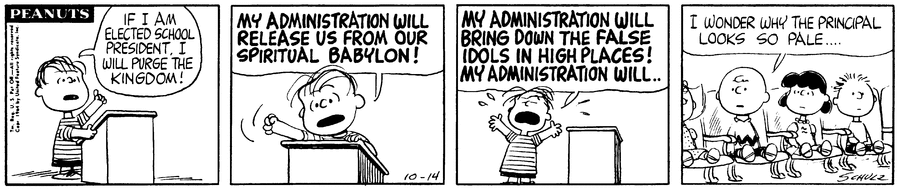

Charlie Brown (Chad Weber) is indeed not elected, but what the title doesn’t tell you is that it’s actually Linus (Stephen Shea) who is running for school president with Lucy (Robin Kohn) as his ruthless campaign manager. This special is a great satire of the election process in the USA and much of its humor is still relevant. A scene of Linus doing a radio call in show is especially hilarious. While it’s adapted from a storyline in the comic strip, this special lengthens the plot a bit, making it more suspenseful, and has several jokes of its own. So even if you remember the premise from the newspaper, you should still give it a viewing.

They used to air You’re Not Elected on TV every year after It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown. Maybe they still do. But they edited it to make time for commercials and I’m sorry to state that they butchered it. Jokes were cut and sometimes punchlines were kept without their proper setups. The pacing and comedic timing were totally ruined. If you’ve only seen the edited for television version of this special, you haven’t seen it.

There’s No Time for Love, Charlie Brown (1973)

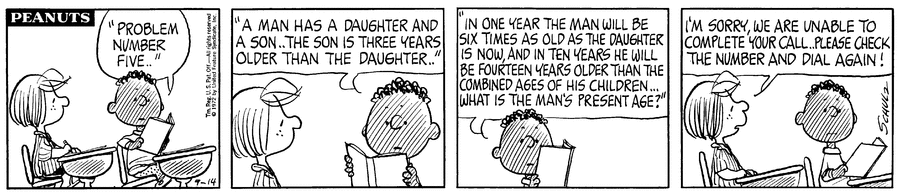

This special begins with a seven-minute montage of the characters struggling in school. It’s basically a bunch of thematically related strips from the 70s one after the other. Some may find this lazy, but I love it. This montage is hilarious and, for someone like yours truly who looks back on their education with little fondness, perfectly captures the futility of school, best exemplified by this quote from Linus (Stephen Shea): “Well, I think that the purpose of going to school is to get good grades so then you can go on to high school; where the purpose is to study hard so you can get good grades so you can go to college; and the purpose of going to college is so you can get good grades so you can go on to graduate school; and the purpose of that is to work hard and get good grades so we can get a job and be successful so that we can get married and have kids so we can send them to grammar school to get good grades so they can go to high school to get good grades so they can go to college and work hard…”

Before too long a plot emerges with Charlie Brown (Chad Weber) needing to get a good grade on his report on a field trip to the art museum. When he gets there, there’s a hysterical mix-up, which I won’t spoil for those who haven’t watched this special. Suffice to say that this is one of the funniest Peanuts stories ever. Nor is it lacking in drama as it’s an interesting exploration of the love triangle between Charlie Brown, Peppermint Patty (Christopher DeFaria) and Marcie (Jimmy Ahrens.) It’s a bit odd that both this special and It’s the Easter Beagle, Charlie Brown portray Marcie as the dumb one when she’s arguably the smartest character in the comic strip.[5]Of course, she is the only one who freely enters into Snoopy’s WWI flying ace fantasies, but does that make her dumb or smart? Both the specials and the strip were written by Charles M. Schulz so it’s not a case of Depending on the Writer. Anyway, moving on…

It’s a Mystery, Charlie Brown (1974)

In this special, Woodstock’s nest vanishes and Snoopy searches for the thief. (Both of them are voiced by Bill Melendez as always.) Despite the title this actually isn’t a mystery as an early scene pretty much gives away the culprit’s identity. What it is, is a great comedy. Some Peanuts fans who don’t care as much for the silent comedy of Snoopy and Woodstock may not love it, but I do. (I’m especially fond of the way the bubble pipe Snoopy “smokes” in his detective persona keeps inconveniencing Woodstock.) And it’s not like there’s no verbal comedy as Snoopy interrogates various Peanuts characters. Linus (Stephen Shea) only has four lines, but he makes every one of them count. And it all culminates in a trial scene which is one of my favorite set pieces in Peanuts animation. Check it out.

It’s Arbor Day, Charlie Brown (1976)

OK, I have to admit that this isn’t as great as the other specials on this list, mainly because the voice acting isn’t on the same par. In particular, Gail Davis is kind of annoying as Sally. (It’s true that she’s supposed to be a shrill character, but I’ve heard plenty of other Sallies who were shrill without being so annoying.) But it is one of the best written Peanuts specials. Sally has to do a report on Arbor Day, which leads to her planting a garden and where she plants it and how it plays out is…well, let’s just say it’s perfect.

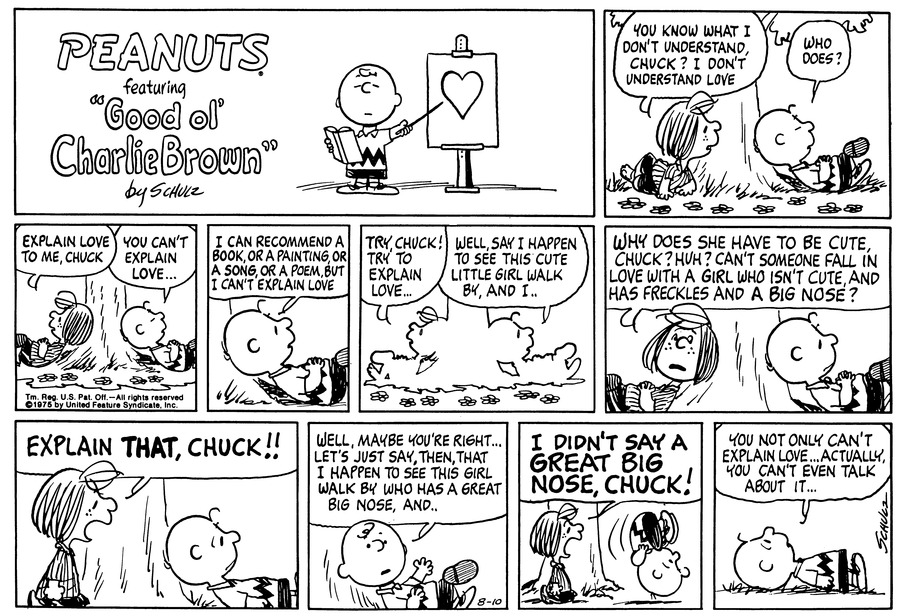

This is just a list of the Peanuts specials I consider the most underrated. It is not a list of the only underrated Peanuts specials or the only good ones. The 1960s gave us such great ones as You’re in Love, Charlie Brown and He’s Your Dog, Charlie Brown. It’s the Easter Beagle, Charlie Brown (1974) features a hilarious subplot about Marcie learning to color Easter eggs and a great ending which makes for an interesting counterpoint to It’s the Great Pumpkin. Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown (1975) has a wonderful scene of Snoopy putting on a romantic “paw-pet” show and a clever bit where he provides visual accompaniment for Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s How Do I Love Thee? (It makes sense in context.) It’s true that the music and voice acting in these specials took a bit of a drop in quality in the 1980s, but some from then were still worth a look. Is This Goodbye, Charlie Brown? and Snoopy’s Getting Married(!), Charlie Brown adapted highly dramatic storylines from the comic and made them even more dramatic. And while the specials in the 2000s, such as A Charlie Brown Valentine and I Want a Dog for Christmas, Charlie Brown, arguably suffered a bit in the writing department from the passing of Charles Schulz,[6]Technically, they were still written by Schulz as they were directly adapted from his comics, but they didn’t always do as good of a job of stringing thematically related comics together into a … Continue reading they featured some great vocal performances, such as those of Ashley Rose as Lucy and Corey Padnos as Linus. If you’ve confined your viewing of Peanuts specials to Halloween, Thanksgiving and Christmas, I hope I’ve made a good case that that should change.

References

| ↑1 | Well, OK, they’re not literally countless. You can count them but it’s intimidating. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | If you’re American anyway. If you’re from another country, you may not even be familiar with those. |

| ↑3 | I, myself, sometimes think It’s the Great Pumpkin is a little overrated but that’s not worth a fight. |

| ↑4 | I’m actually doing this as both a YouTube video and a blog post. If you’d like to watch the video version (and check out of my extremely modest YouTube channel), here it is, but I warn you I’m much better at writing than speaking, so this blog version is better. |

| ↑5 | Of course, she is the only one who freely enters into Snoopy’s WWI flying ace fantasies, but does that make her dumb or smart? |

| ↑6 | Technically, they were still written by Schulz as they were directly adapted from his comics, but they didn’t always do as good of a job of stringing thematically related comics together into a special. |