Note: Originally, this post wasn’t going to be published for quite some time. But with the passing of Bob Newhart, who memorably lent his voice to a main character in one of the movies under discussion, I decided to go ahead with it now as a tribute to him.

Animation critics and historians generally regard the 1970s as the beginning of a dark age for Walt Disney animation that last until roughly 1989.[1]Actually, some critics would say this dark age started with the 60s and even pickier ones would say it actually began right after the release of Bambi. This, they’d say, coincides with the death of Walt Disney himself. Now I don’t buy the idea that the Disney company needed its namesake to make great animated movies. From what I understand, he’d already begun to pay more attention to live action cinema and theme parks during the 50s and I’d say they were still going strong then though that opinion isn’t universally shared by critics. And even when he’d been the guiding force behind the animation studio, he wasn’t the only one with ideas. Neither were his ideas always great. The man wanted to cut the iconic spaghetti scene from Lady and the Tramp for crying out loud! That being said, if you wanted to make the argument that Disney animation couldn’t survive without Walt Disney, The Aristocats (1970) would strongly support your case, much as it pains me to say so as a cat person.[2]Actually, I’m not really a pet person but if I were, I’d be a cat person.

Based on a story by Tom McGowan and Tom Rowe, the movie begins with a Parisian millionaire (voiced by Hermione Baddeley)[3]Disney fans may be interested to note that she also played the maid in Mary Poppins. As a Dickens fan, I remember her for playing Mrs. Cratchit in Scrooge (1951) and Mrs. Bardell in The Pickwick … Continue reading) leaving her entire fortune to her beloved cat, Duchess (Eva Gabor), and her three kittens, Toulouse (Gary Dubin), Marie (Liz English) and Berlioz (Dean Clark.) A second beneficiary is her butler and the cats’ caretaker, Edgar (Roddy Maude-Roxby.) Not taking this well, Edgar drugs the cats and leaves them in the middle of nowhere at night. Not understanding what has happened, they journey back to Paris with the help of stray cat, Thomas O’ Malley (Phil Harris.)

The Aristocats really feels like a fusion of three Disney movies that had recently done well, only not as good as any of them. Most obviously and shamelessly, the romance between Duchess and O’ Malley is straight from Lady and the Tramp. Again, we have a sheltered, ladylike female pet, loyal to her human owner but separated from them, helped by a worldly wise, roguish but ultimately goodhearted male stray who thinks of humans as either enemies or beings to be exploited. Again, we have a scene where the male invites the female to share a life with him, but she regretfully declines out of loyalty to her owner. Again, the male proves his mettle in the end by saving the day and the female’s owner adopts him. Even the names of the leading ladies aren’t that far removed from each other! Still, the addition of three kids, even if they’re not very memorable themselves, does shake up the dynamic a bit. So does the fact that Duchess is less naive than Lady and responds to O’ Malley’s flirting in kind. All in all, the Lady and the Tramp parts of the Aristocats are probably the parts that work best, dramatically speaking.

Less obviously but unmistakably once you notice it, the movie follows in the pawprints of 101 Dalmatians with a family of pet characters, including kids, living in a European capital, abducted by a villain, and journeying across the countryside back to their owner. But The Aristocats, unlike Dalmatians, seldom plays the material for suspense. Instead, it takes its tonal cues from The Jungle Book (1967), being a road trip comedy, whose plot is largely an excuse for encounters with comedic talking animals, many of them modeled on the most famous personas of the celebrities voicing them. We even get a group of jazz playing animals (swinging apes in The Jungle Book, hep alley cats in The Aristocats), the leader of whom, Scat Cat (Scatman Crothers), is, like Louis Prima’s King Louie of the Apes, modeled on the musician providing his voice[4]Actually, he was supposed to be voiced by Louis Armstrong but that didn’t work out., and who also give a show stopping musical number in a long abandoned human dwelling they end up damaging. Said musical number is even about wanting to be someone. Credit where credit is due though: Everybody Wants to Be a Cat is the only song from this movie most people remember. (Personally, my favorite of the songs is Thomas O’ Malley Cat.)

The character animation for The Aristocats is fine but lacks the great comedic timing of The Jungle Book.[5]I wouldn’t say either film has a lot of great verbal humor, but The Jungle Book‘s character animation makes it more entertaining (for kids anyway) than it has a right to be. The fact that the animals it features are considerably less exotic doesn’t help. And the story just isn’t as dramatic as that of 101 Dalmatians. We’re told that the cats’ journey is arduous more than we’re shown it and honestly, we’re not even told that it’s arduous that often. The story structure precludes the villainous Edgar from threatening the heroes until they finally reach their destination in the last act. To keep viewers from forgetting about him, the movie indulges in a pointless subplot. The implied reason Edgar abandons the pets rather than drowning them is that he gets chased by a couple of overzealous farm dogs, Napoleon (Pat Buttram) and Lafayette (George Lindsey.)[6]Why give such obviously French names to characters with rural American accents? Your guess is as good as mine. He later realizes that he left his motorcycle’s sidecar, his bowler hat and his umbrella at the farm and has to go retrieve them lest the police trace the items back to him. The cats’ friend, Roquefort the mouse (Disney veteran Sterling Holloway)[7]Yes, the cats are friends with a mouse, tries to hitch a ride with Edgar back to the scene of the crime to find Duchess and her kittens. He doesn’t succeed and even if he did, we know the cats have already left, so who cares? The first chase scene with the dogs is more painful than funny.

But the second scene is a comedic highlight of the movie. Weirdly though, it makes more sense if we’re supposed to root for Edgar the bad guy.

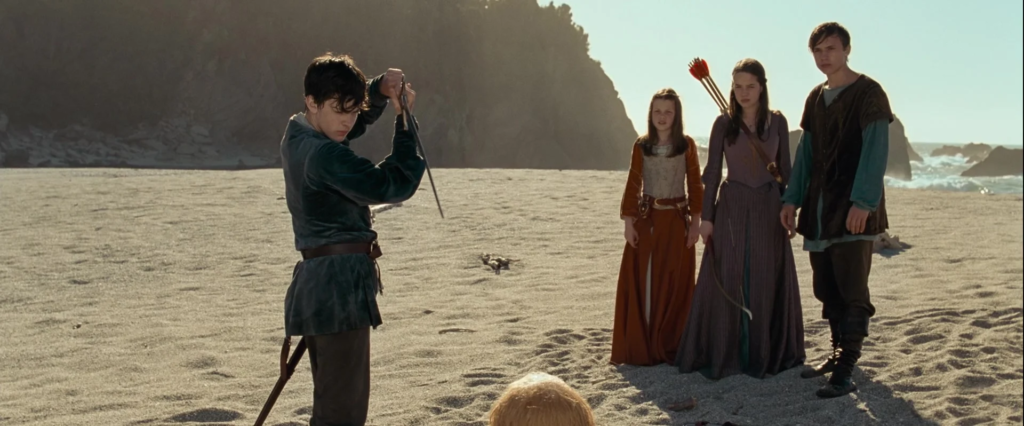

Fortunately, once the cats reach their destination, the story finally becomes exciting as Edgar stuffs Duchess and her kittens in a sack and O’ Malley, Roquefort and the alley cats have to rescue them. The movie’s humor also picks up at the climax with some laugh-out-loud visual gags. The final minute even contains a great variation on a running joke with the dogs. (“Wait a minute! I’m the leader! I’ll say when…”) Even more fortunately, Disney’s next animated movie, the 1973 Robin Hood, a retelling (sort of) of the familiar English legend with anthropomorphic animals as the characters, would be a big step up from The Aristocats.

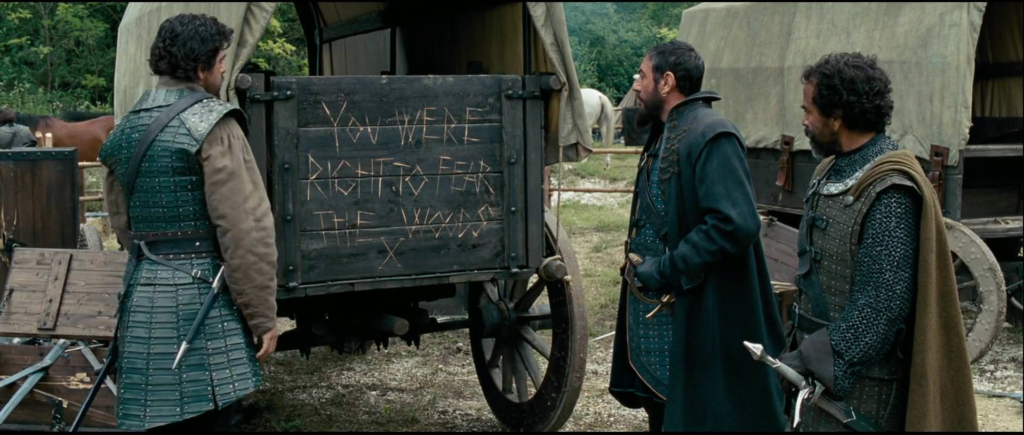

If Fantasia, as I’ve written before, is an animated Disney movie that’s enjoyed by analytical critics but not by your average moviegoer, Robin Hood is the opposite. Historically, it’s been dismissed, if not savaged, by film critics and liked, nay, loved by “normal” people. The movie is primarily a comedy, and I can’t really explain why fans find it hilarious and others don’t, humor being so subjective. But maybe I can illuminate some other things. The film’s visuals tend to be serviceable at best. The backgrounds are fine but undistinguished. We’re a long way from Gustaf Tenggren, Mary Blair or Eyvind Earle.

The character animation is likewise fine, but it lacks the extra artistry and wit that make Disney animation at its best appealing to the analytical eye.[8]This movie also has an unusually high number of bits where the animators clearly just traced over animation from the company’s other movies. One would assume this was to save money but, … Continue reading The only character who is really fun to watch is the villainous Sir Hiss (Terry Thomas.)

For critics interested in story structure, the movie doesn’t have much to offer either. It (sort of) builds to a climax and a pretty fun one too, involving a massive jailbreak/heist and a burning castle, but it only builds to it in the loosest sense of the term. Most of the film is just a meandering series of scenes, each of which naturally leads into the next but not without really building much momentum. The story’s main problem is resolved entirely offscreen. Some of the scenes don’t even try that hard to be funny. But I’ve never really had a problem with episodic storytelling. I’d argue it makes sense for Robin Hood, considering the source material, even if episode storytelling can be done better. I’d also argue that those less humorous scenes serve the purpose of endearing us to the characters.

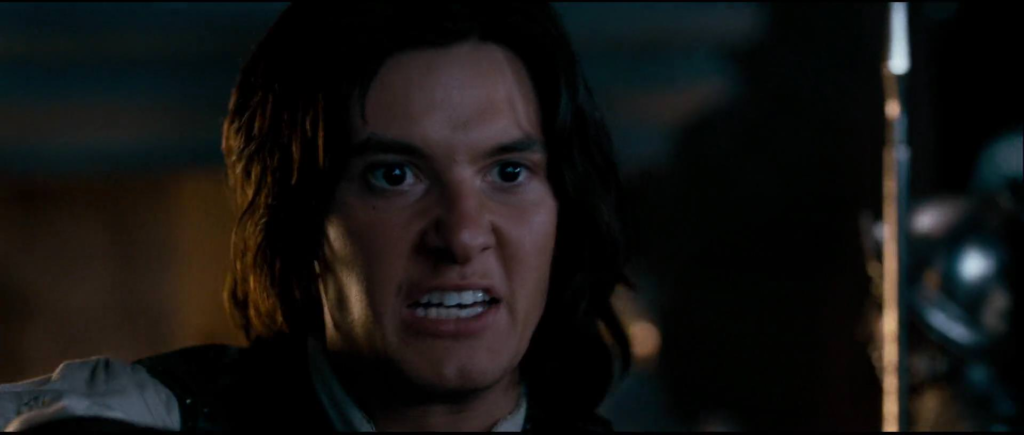

That’s the movie’s real strength. It has a fun, likeable cast of characters and a lot of great vocal performances, starting with Brian Bedford’s as Robin Hood himself. Not only is he fun and charming when the character is speaking normally but he also shows an impressive range as the various alter egos he adopts. I like that the movie has Robin Hood genuinely be a master of disguise when it would have been easier to just have his enemies be ridiculously gullible. Phil Harris as Little John doesn’t even try to alter his voice when his character goes undercover but he’s great fun anyway and the animators do their best to disguise the distinctive character design.[9]Speaking of range, I’ve read some call Little John a recycled version of Baloo from Disney’s The Jungle Book, but I’d argue that while both characters are bears voiced by Phil … Continue reading

I also like that, effective as Robin’s disguises are, Prince John (Peter Ustinov) sees through one in a big scene, making him a somewhat formidable villain and not just a pathetic dupe. Instead, he’s 98% a pathetic dupe and a hilarious one. Ustinov’s vocal performance is the funniest in the movie and that’s saying something. As long as Prince John and his aforementioned sidekick, Sir Hiss, are onscreen together, and especially when they’re mad at each other, the movie is a hoot.

Other fun characters are the gleefully sadistic sheriff of Nottingham (Pat Buttram),[10]In olde England, a sheriff was the king’s representative in a county but the movie to avoid taxing American audiences (see what I did there?), portrays him as a sheriff from a western, complete … Continue reading, the jolly when not angered Friar Tuck (Andy Devine) and the pugnacious Lady Kluck (Carole Shelley), sidekick to Maid Marian (Monica Evans.)[11]Yes, foxes are friends with chickens in this movie and with rabbits. You’ve just got to go with it.

Something else I like is that the movie devotes a fairly lengthy scene to Robin Hood helping the oppressed poor of Nottingham. It isn’t as fun to watch as the scenes of him robbing Prince John but it’s a big part of his previously mentioned likability. This movie also boasts one of the best Disney soundtracks from the 70s. Not all of the songs by Roger Miller, who also voices Allan-a-Dale the minstrel, are great but all of them are pleasant and one of them, The Phony King of England, is one of the best songs to come from a Disney movie of any decade. Why don’t you give it a listen right now?

Ultimately, I agree with the mainstream audiences that Robin Hood is a very fun movie. However, I can’t resist mentioning that twenty-one years prior to this take on the Robin Hood legend, Disney released what I consider a better one, The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men, and too few people have seen that in my opinion.

1977 saw the release of The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, a truly delightful movie but one which was mainly composed of three preexisting featurettes, two of which had been made in the 60s. Thus, it’s not particularly indicative of 1970s Disney animation.[12]Well, you could argue there wasn’t much stylistic difference between the animated content Disney made in the two decades, but I feel like there was a kind of ambition in their 60s output you … Continue reading It’s also adapted from two great books, so I’d prefer to devote a whole blog post to it as part of The Adaptation Station and not one of these Animation Station bonus thingies. Moving on…

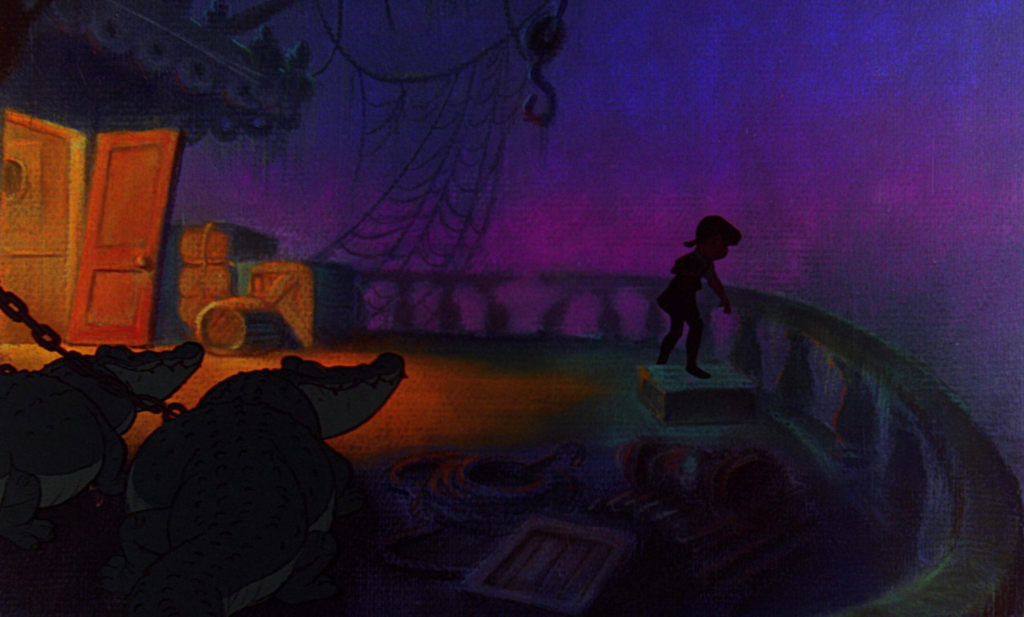

It’s rather jarring to go from either Robin Hood or The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh to The Rescuers (1977.) It opens with one of the darkest, most ominous openings to any animated Disney film. Before the credits begin, we see a rickety old riverboat at night in a bayou somewhere in Louisiana. A little girl backs out of the boat’s interior and onto the deck as if she’s terrified of being seen. Two fearsome looking crocodiles on chains[13]They’re referred to as “crocs” in one line of dialogue, but from what I understand the designs are inconsistent as to whether they’re those or alligators. watch her. Furtively, the girl drops a bottle with a message in it into the water.

“Who will rescue me?” Shelby Flint hauntingly sings in the first of the movie’s pleasant 70s-style pop songs. We follow the bottle’s tumultuous journey to New York harbor where it is found by mice, the least likely creatures to be able to help. Or are they?[14]OK, technically, bugs would be less likely rescuers. I consider this one of the most gripping openings, if not the most gripping, to any Disney movie though I admit it would probably be even better if the bottle’s journey was fully animated instead of shown to us through a series of paintings by Mel Shaw. But, hey, they’re good paintings.

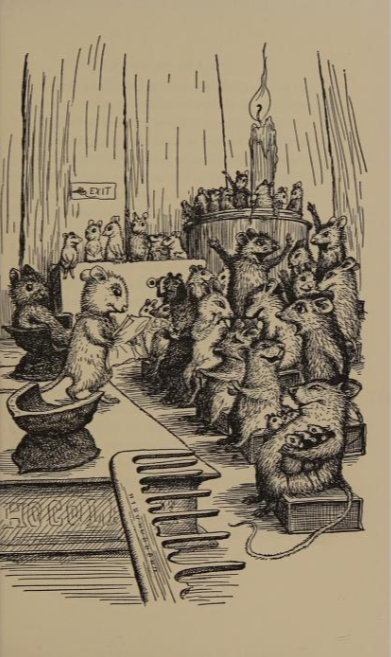

Beneath the United Nations building, the bottle is brought before a meeting of the Rescue Aid Society, an international organization of mice dedicated to rescuing people. The message tells them that Penny, its writer, is in terrible trouble and needs help but the part that would have told her location has been rendered illegible by water. Miss Bianca (Eva Gabor), a glamorous member of the society who appears to lead a rather cushy life, is moved by the letter and to everyone’s surprise, volunteers to go on the rescue mission. When the chairman (Bernard Fox) suggests she take someone with her, every male agent eagerly raises their hand but Miss Bianca further surprises by choosing the humble, scruffy janitor, Bernard (Bob Newhart.) (The implication is that she’s attracted to him by the way, not that she’s worried about one of her fellow agents harassing her.)

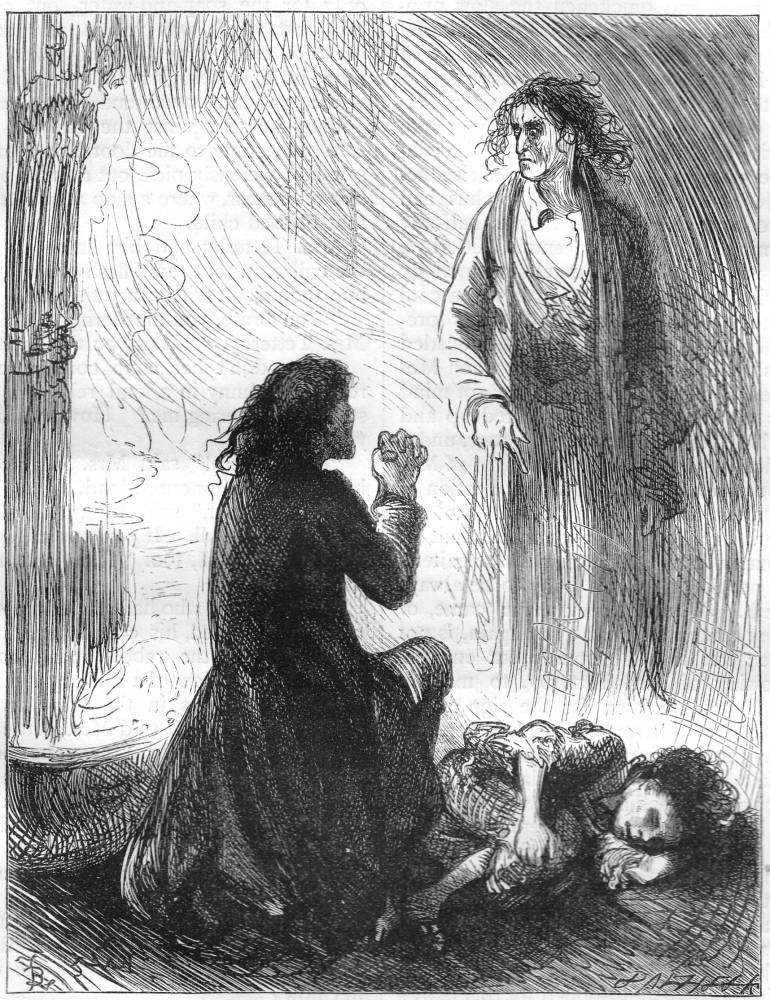

Does the idea of an international organization of mice dedicated to rescuing people sound a bit random to you? Well, it made more sense in the children’s books by Margery Sharp that inspired this movie. There it was called the Mouse Prisoners Aid Society, and it played on the literary convention of prisoners befriending mice in their cells and taking comfort from them. That was the service the society had always provided at the beginning of the first book, published in 1959, but it quickly evolved into a society for busting prisoners out. The movie takes its title from that first book, but its story has much more in common with the second book, Miss Bianca (1962), with an orphan girl whose name begins with a P being held captive by an evil woman with a pathetic male sidekick and two guard animals. It’s really only an adaptation in the loosest sense of the word though. But while I prefer the book series[15]Well, the first three or four books in it anyway. Margery Sharp was forced to continue writing the series long after it should have ended, and the stories became increasingly dumb., but the movie benefits from following its formula. As in your average Miss Bianca book, we see the heroes track down the prisoner they need to liberate, make contact with them, devise an escape plan, put the plan into action, experience some setbacks and ultimately triumph.[16]Sorry if that’s spoiling anything. I assume everyone knows children’s stories usually have happy endings.

The movie also benefits from keeping the characters of Bernard and Bianca close to their literary versions. Well, they’re pretty close. Bernard is a bit more bumbling and fearful, but he still proves invaluable in a real crisis. Miss Bianca doesn’t get the character arc she had in the first book in which she had to be convinced to go on a dangerous mission and was initially uncomfortable talking to members of the lower classes. But that character arc was really finished in one book. The movie’s selfless, risk-taking Miss Bianca who can talk to anyone is pretty much the character we get in every other book in the series. She and Bernard are actually some of my favorite animated lead characters. Something about The Rescuers that was unique for the time was the way that their relationship was portrayed. They were attracted to each other from their first scene, but this was handled as a subtext. And they clearly bonded with each other over the course of the movie, it was never a love story with wedding bells explicitly ringing at the end. The focus was on their mission, not their romance.[17]A beef I have with the later sequel, The Rescuers Down Under, is that the entire middle section consists of repetitive scenes of Bernard and Bianca traveling across the Australian outback to find the … Continue reading

This movie has a much more threatening villain than any other Disney animated movie from the 70s. True, Madame Medusa (Geraldine Page), looks like a comical figure at first glance. But while she’s definitely over-the-top and caricatured, she can be quite disturbing in the way that dangerously unhinged, obsessive people willing to endanger children to get what they want are disturbing.

Her crocodiles, Brutus and Nero, are also very intimidating and the movie makes great use of their size during action scenes.

They can also be quite funny, most notably in a scene where Bernard and Bianca take refuge from them in a pipe organ and the crocs try to flush them out by playing it.

The Rescuers has less in common with the lighthearted cartoon comedies Disney typically made the 70s than it has with the animated films the studio would make in the 80s featuring more intense villains, darker visuals, occasional morbid humor and violent action climaxes.[18]The Little Mermaid (1989) is generally seen as the prototype for 90s Disney animated features rather than the culmination of the 80s ones but everything I’ve just written about them applies to … Continue reading

But there are still some elements that cross over. (I don’t mean that as a bad thing by the way.) Pat Buttram and George Lindsey, who were in both The Aristocats and Robin Hood, voice supporting characters. So does John Fiedler who was in both Robin Hood and The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. Orville (famed radio performer Jim Jordan) the clumsy yet naively confident albatross who gives Bernard and Bianca a ride on his back feels like he could have come from any of the Disney movies had come recently. So does Evinrude the long-suffering dragonfly ferryman.[19]Ferrydragonfly? Perhaps neither is as memorable as the Robin Hood sidekicks but they’re better than those in The Aristocats.

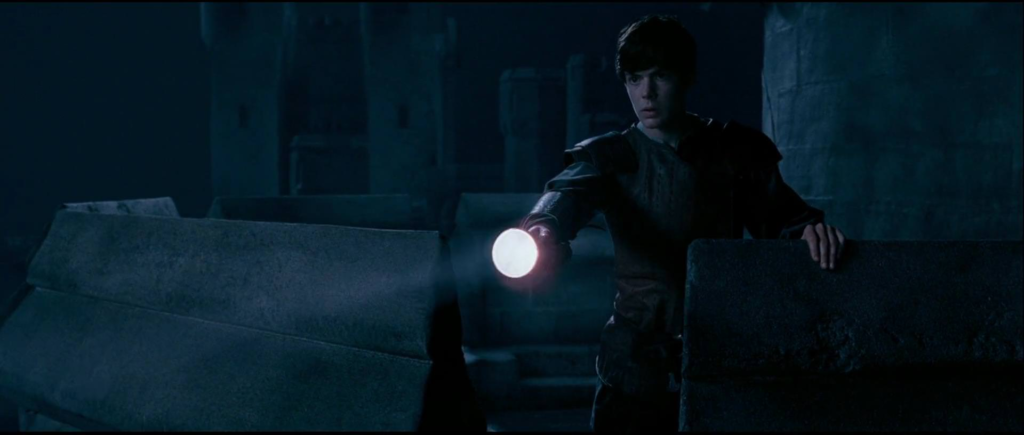

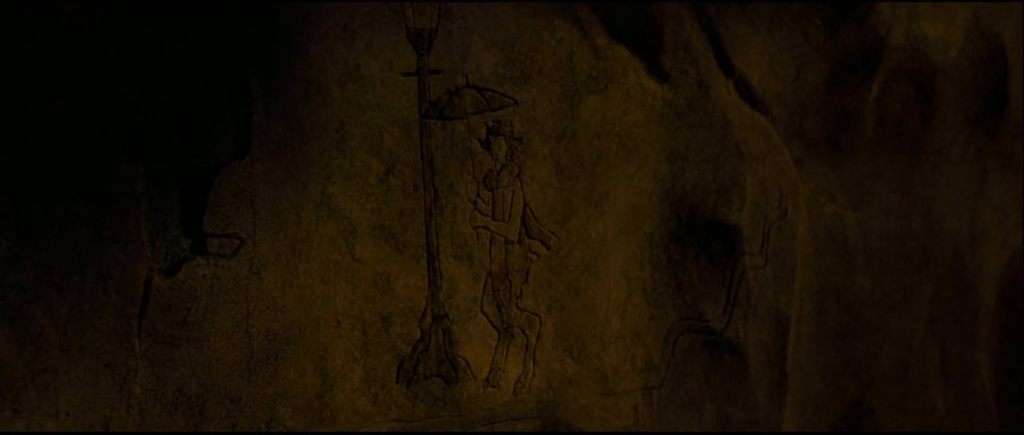

The movie kind of has two climaxes. First, a rather dark and intense one with Penny and her rescuers trapped in an underground cave that fills up water.[20]Yes, there’s apparently a strong tide in this bayou. Then there’s a more comical, slapstick climax that sees the bad guys get their comeuppance. Even that one throws more than a few unexpected obstacles in our heroes’ way, making it more genuinely suspenseful than the similar climaxes of The Aristocats and Robin Hood.[21]Well, I’d argue that last one was a little suspenseful. Both scenes are great in their own ways.

Not everything about The Rescuers works brilliantly and it’s not a movie for everyone. But it is a movie for some people, and I am one of them.

So, were the 1970s a dark age for Disney animation? I can’t really say that since I like all but one of these movies and I don’t hate the one I don’t like. And not discussing The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh really does make the decade sound less impressive for Disney than it was.[22]To be fair, when critics speak of “the dark of age of (mainstream American) animation,” they’re usually referring to both the 70s and the 80s. But it was a very unambitious age. I remember when I was blogging my way through the various movies the studio made during the 1940s that were compilations of short cartoons. Pretty much any Disney animated film from the 70s has a bigger fanbase than those and there are reasons for that. Yet I can still tell that, for all their budget limitations, the creators of those compilation movies were still trying take viewers to strange and fantastical worlds, the likes of which they’d never seen before. By contrast, except for The Rescuers, none of these 70s movies aims for anything more than getting some laughs and creating some endearing characters. And on bad days, they can’t even accomplish that. Even if you’re just looking for a fun Disney animated comedy, I’d say The Sword in the Stone from 1963 is funnier and more interesting than all but their best from the 70s. Maybe we should call the decade the Dim Age of Disney Animation.

Eh, that sounds way too harsh. Like I said, there’s far more good than bad here. If what you (or your kids) seek from Disney animation is fun turn-off-your-brain Saturday morning entertainment, this is the decade for you.

References

| ↑1 | Actually, some critics would say this dark age started with the 60s and even pickier ones would say it actually began right after the release of Bambi. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Actually, I’m not really a pet person but if I were, I’d be a cat person. |

| ↑3 | Disney fans may be interested to note that she also played the maid in Mary Poppins. As a Dickens fan, I remember her for playing Mrs. Cratchit in Scrooge (1951) and Mrs. Bardell in The Pickwick Papers (1952. |

| ↑4 | Actually, he was supposed to be voiced by Louis Armstrong but that didn’t work out. |

| ↑5 | I wouldn’t say either film has a lot of great verbal humor, but The Jungle Book‘s character animation makes it more entertaining (for kids anyway) than it has a right to be. |

| ↑6 | Why give such obviously French names to characters with rural American accents? Your guess is as good as mine. |

| ↑7 | Yes, the cats are friends with a mouse, |

| ↑8 | This movie also has an unusually high number of bits where the animators clearly just traced over animation from the company’s other movies. One would assume this was to save money but, according to some animators, it didn’t actually accomplish that. I don’t really mind myself though it does mean there’s an entire dance scene where none of the choreography particularly matches the music. |

| ↑9 | Speaking of range, I’ve read some call Little John a recycled version of Baloo from Disney’s The Jungle Book, but I’d argue that while both characters are bears voiced by Phil Harris, they have opposite personalities. |

| ↑10 | In olde England, a sheriff was the king’s representative in a county but the movie to avoid taxing American audiences (see what I did there?), portrays him as a sheriff from a western, complete with badge. |

| ↑11 | Yes, foxes are friends with chickens in this movie and with rabbits. You’ve just got to go with it. |

| ↑12 | Well, you could argue there wasn’t much stylistic difference between the animated content Disney made in the two decades, but I feel like there was a kind of ambition in their 60s output you don’t get in the 70s stuff. |

| ↑13 | They’re referred to as “crocs” in one line of dialogue, but from what I understand the designs are inconsistent as to whether they’re those or alligators. |

| ↑14 | OK, technically, bugs would be less likely rescuers. |

| ↑15 | Well, the first three or four books in it anyway. Margery Sharp was forced to continue writing the series long after it should have ended, and the stories became increasingly dumb. |

| ↑16 | Sorry if that’s spoiling anything. I assume everyone knows children’s stories usually have happy endings. |

| ↑17 | A beef I have with the later sequel, The Rescuers Down Under, is that the entire middle section consists of repetitive scenes of Bernard and Bianca traveling across the Australian outback to find the prisoner they hope to rescue and Bernard fretting about his relationship with Bianca. They only meet the child they’ve come to help when the movie is almost over and never forge anything like the bond they built with Penny. Neither do we see them planning the escape. But I know there are people out there who consider The Rescuers Down Under an improvement on the original so don’t take my word for it. |

| ↑18 | The Little Mermaid (1989) is generally seen as the prototype for 90s Disney animated features rather than the culmination of the 80s ones but everything I’ve just written about them applies to it too. Pay attention to some of the lyrics Under the Sea sometime. They’re pretty dark. |

| ↑19 | Ferrydragonfly? |

| ↑20 | Yes, there’s apparently a strong tide in this bayou. |

| ↑21 | Well, I’d argue that last one was a little suspenseful. |

| ↑22 | To be fair, when critics speak of “the dark of age of (mainstream American) animation,” they’re usually referring to both the 70s and the 80s. |