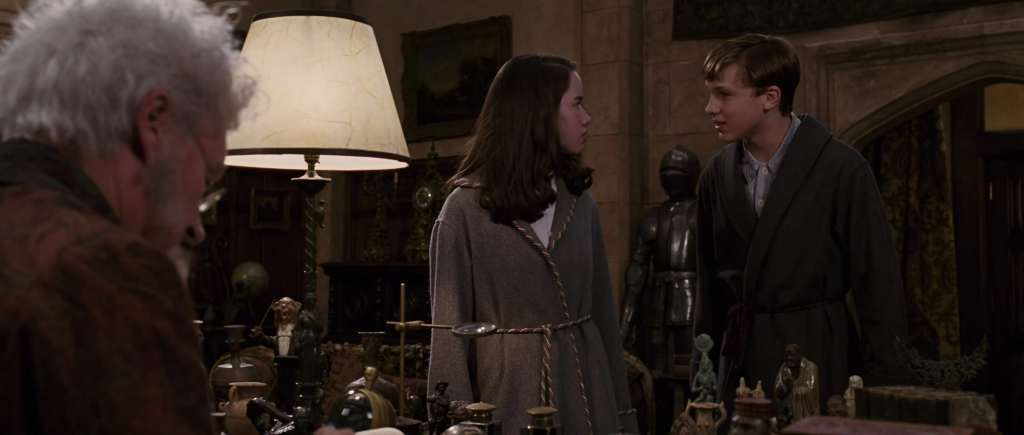

The Pevensies and the beavers are trudging across a vast frozen lake. There’s a nice transition from the white landscape to the white sky. Mr. Beaver, who is far ahead, calls behind him, “Come on, humans! While we’re still young.” Peter takes the weary Lucy on his back. “If he tells us to hurry one more time,” he says, “I’m going to turn him into a big fluffy hat!” William Moseley’s line reading indicates that he’s less annoyed with Mr. Beaver than trying to cheer up Lucy with humor. This is noteworthy in retrospect because in this movie’s sequel, Moseley’s performance would pass up on most of the opportunities it had to make Peter likeable. “Come on,” Mr. Beaver calls again. “He is getting a little bossy,” says Lucy. “No, behind you! It’s her!” cries Mrs. Beaver. The Pevensies turn around and see a sleigh in the distance. Lucy gets off of Peter and they race for their lives. Sharp-eyed viewers, unfamiliar with the book, will be able to guess that this a misdirect when we see that the sleigh is being drawn by reindeer but they’re gray rather than white like the White Witch’s deer. (In the book, they were brown. Maybe the filmmakers thought gray would be less obviously not white than brown would be.) Fans will already be able to guess what’s coming.

Our heroes hide in a ditch. They hear the sleigh stop and see a tall shadow pass over them.

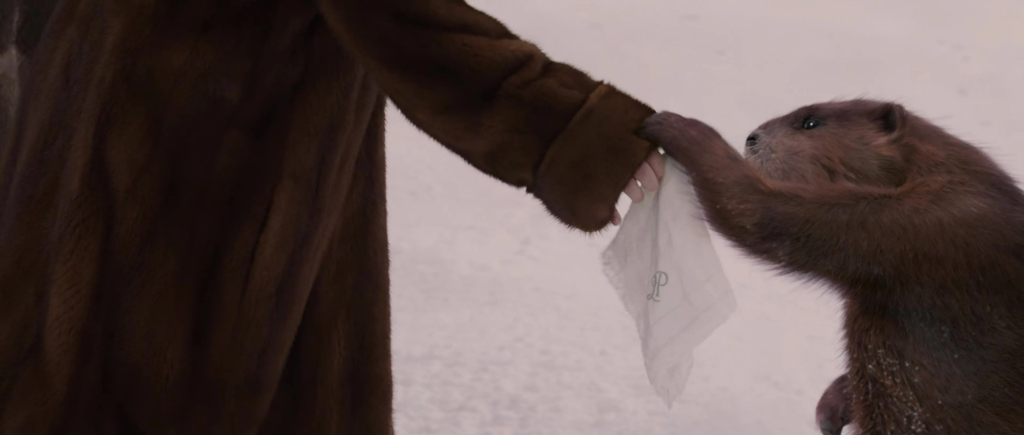

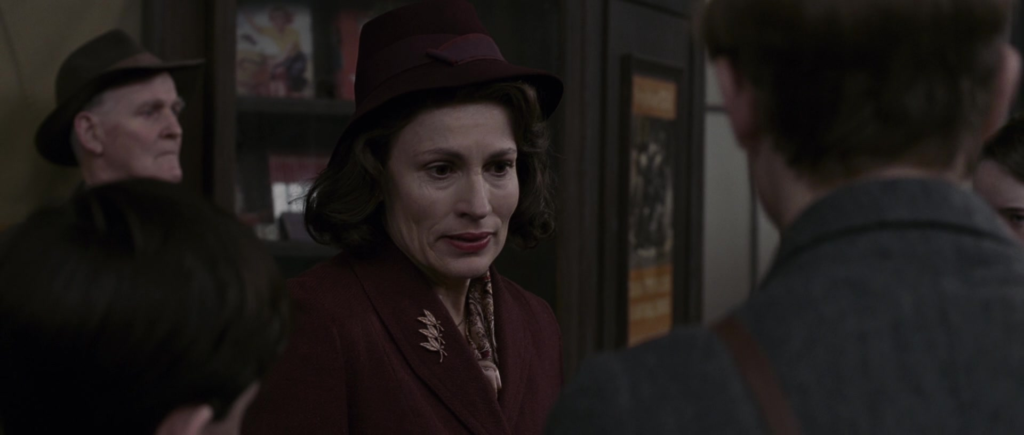

Peter reluctantly volunteers to get out and check to see if its’ safe, but Mr. Beaver insists on being the one to do so, saying, “you’re worth nothing to Narnia dead.” There’s a nice they-really-do-love-each-other moment as Mrs. Beaver objects that her husband isn’t worth anything dead either. He appreciates the sentiment but sneaks out of hiding anyway. After a tense moment, his head pokes down over the culvert’s upper lip. “Come here! Come here,” he says, ” I hope you’ve all been good because there’s someone here to see you!” They climb up out of hiding to see a white-bearded man (James Cosmo) in red[1]Actually, it’s more of a brown but whatever. standing in front of the sleigh. Lucy’s face lights up. “Merry Christmas, sir,” she says. “It certainly is, Lucy,” he replies, “since you have arrived.” Yes, this is Father Christmas.[2]They never say his name aloud in the movie, presumably because American kids might not be familiar with it. Not saying the name allows them to assume it’s Santa Claus while English kids can … Continue reading

The inclusion of this character in the story of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe has always been controversial. Both the people to whom C. S. Lewis showed his draft felt he didn’t fit but Lewis stubbornly insisted on keeping him. Unsurprisingly, given that this adaptation has less of an emphasis on charming tea parties and more of an emphasis on military preparations, the filmmakers were tempted to cut Father Christmas and have Aslan give the children their gifts.[3]The 1979 made-for-TV cartoon did the same thing though weirdly they still had another character refer to Father Christmas. Were they speaking literally or metaphorically? But whether it was the insistence of C. S. Lewis’s literary estate, fear of fan backlash or some storytelling instinct of their own, the character was included though their intentions were to portray him “not as a jolly old St. Nick with a bag of video games but as a wise old Norse warrior, returning home after years of battle, full of both hard-earned wisdom and love for the children.” I’d argue that was already how C. S. Lewis depicted him, minus being Norse or a warrior.[4]And, hey, it’s not like Lewis specifically wrote that he wasn’t a Norse warrior.

Some of the pictures of Father Christmas in our world make him look only funny and jolly. But now that the children actually stood looking at him, they didn’t find it quite like that. He was so big, and so glad, and so real, that they all became quite still. They felt very glad, but also solemn.

I actually imagined Father Christmas in the book to be more serious than James Cosmo plays him as being in the movie. He doesn’t go “ho, ho, ho,” but he does chuckle quite a bit throughout the scene, and he shows more of a sense of humor than his literary counterpart, apologizing for scaring the characters but adding, “in my defense I have been driving one of these longer than the Witch.” He does get the glad part though and the music that plays during the scene matches the description of glad-but-solemn quite well. It’s one of my favorite parts of the soundtrack. “I’ve put up with a lot since I got here but this…” Susan whispers to Peter. That line likely reflects the screenwriters’ own reaction to encountering Father Christmas in the source material. If the movie had emphasized the line, I’d probably find the self-aware lampshade hanging annoying, but the director wisely keeps Susan’s incredulity in the background and for the most part, plays the joy of the moment straight. “I thought there was no Christmas in Narnia,” she says out loud. (Nobody’s actually mentioned that to her in this movie that we’ve heard but I suppose we can infer Lucy did so offscreen.) Father Christmas sadly affirms that this has been true for a long time but “the hope that you have brought, Your Majesties, is finally starting to weaken the Witch’s power.” That is probably the line in this adaptation most criticized by fans of the book which portrays Aslan as being responsible for the return of spring and Christmas to Narnia, not the prophesied kings and queens. I’m not as mad as some fans about this, mostly because the change didn’t surprise me. From comments I’d read from the director and just the way the movie itself had been setting up the story, I figured it would be Pevensies’ presence in Narnia that would break the Witch’s spell in this version. It’s considered bad storytelling nowadays to have side characters be the main ones to save the day rather than your heroes, so I had already resigned myself to this inevitable change, annoying as it is for fans of the character of Aslan.

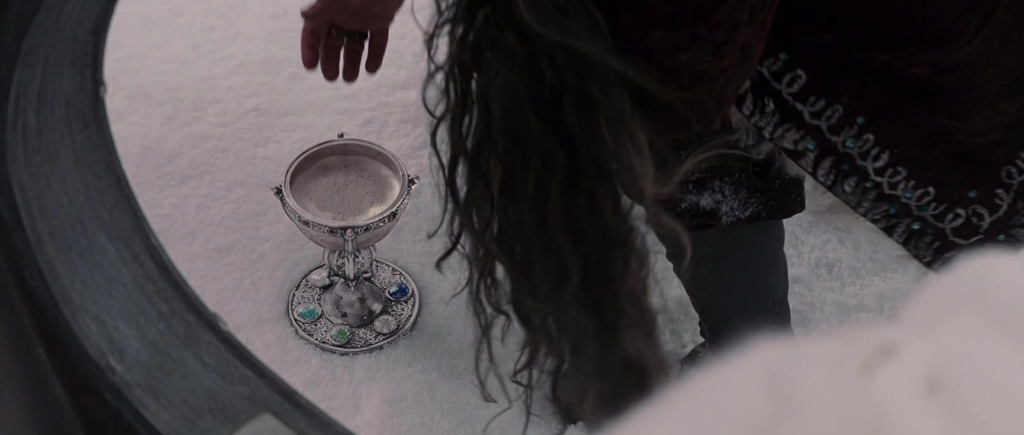

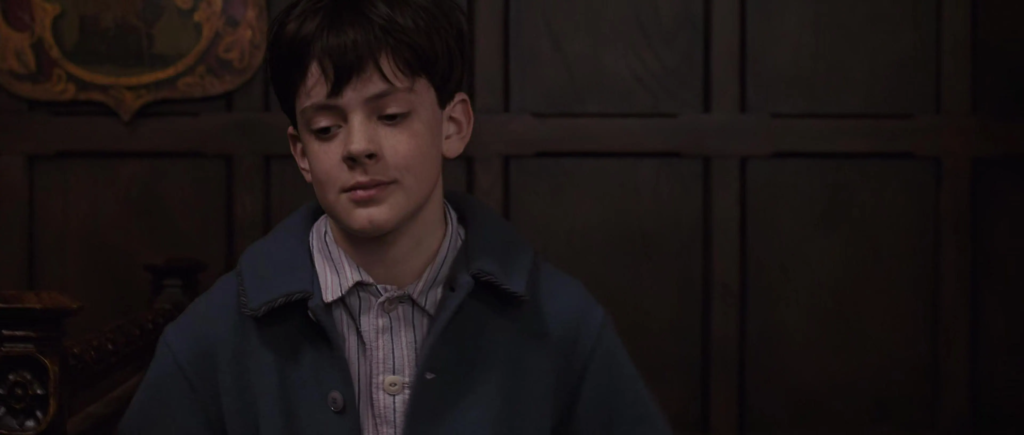

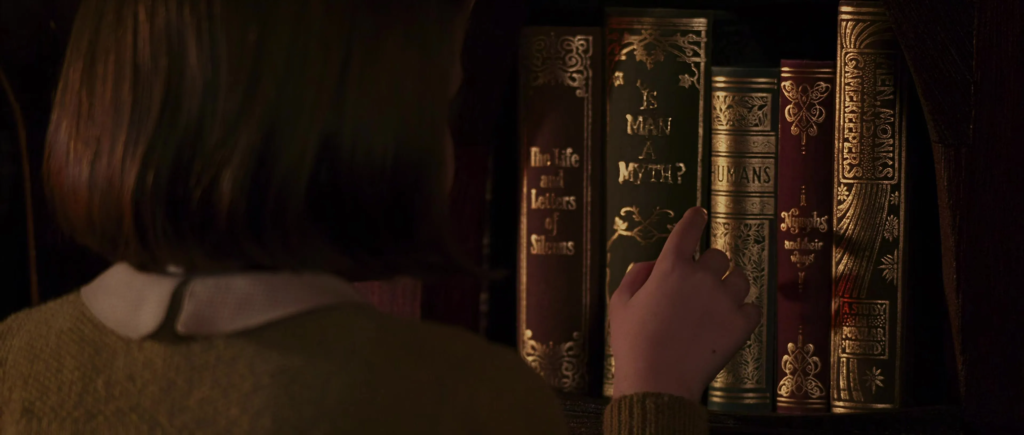

Anyway, even with all the hope they’ve brought, Father Christmas says the Pevensies could probably use some help against the Witch, so he pulls out a sack and gives each of them some gifts. He hands them out in the reverse order that he does in the book. Perhaps this is because the movie wants Peter to be a bigger hero than he was in the book[5]Well, actually he was just as big of a hero in the book, but the book wasn’t particularly interested in his heroism. and so also wants his gift to be the big climax of this scene. First, Father Christmas gives Lucy a bottle. “The juice of the fire flower,” he explains. “One drop will cure any injury.” He also gives her a fancy dagger-the props in this movie are beautifully designed-though he tells her he hopes she’ll never have to use it.

“I think I could be brave enough,” Lucy argues, a little uncertainly. “I’m sure you could,” says Father Christmas, “but battles are ugly affairs.” This is a change from his potentially controversial line from the book, “battles are ugly when women fight.” Personally, I think changing the line was the right idea since it would have seemed like a political commentary on women in the military and I prefer to keep political commentary out of my escapist fantasies.[6]Of course, I understand why writers want to include commentary about issues that are important to them, and I don’t expect them to avoid writing about those issues just to please me. But I … Continue reading Honestly, even if I wanted this story to make a case against women in the military, Father Christmas’s original line doesn’t exactly do that very well. (Battles are ugly by definition.) Then again, you could argue the new version of this line isn’t unanswerable either since other characters are going to be sent into battle despite its ugliness. But to its credit, the movie is going to hang a lampshade on that, one that actually makes me laugh. I think there’s a value to keeping Lucy’s question about whether she should fight in the battle, despite the controversy it invites, since it differentiates her character from that of Susan who is quite happy to just have weapons for self-defense and permission to sit out any battle.[7]In the later Narnia books, The Horse and his Boy and The Last Battle, C. S. Lewis would have his heroines, one of them an older Lucy, take part in battles albeit only as archers. This may not have … Continue readingSpeaking of Susan, Father Christmas gives her a bow and a quiver of arrows. In a fun, whimsical touch, the quiver has her initials (S. P.) on it. “Trust in this bow and it will not easily miss,” Father Christmas tells Susan. “What happened to ‘battles are ugly affairs?'” she objects. “And though you don’t seem to have a problem making yourself heard,” he chuckles, handing her an ivory horn shaped like a lion’s mouth, “blow on this and wherever you are, help will come.” Susan manages a smile and thanks him, though characteristically she still seems a little uncomfortable with these special gifts.

Then it’s Peter’s turn. Father Christmas gives him a sword and a silver shield with a red image of a lion on it. “The time to bear these may be near at hand,” he explains. “These are tools, not toys. Bear them well and wisely.” Peter gravely accepts his gifts and seems much more openminded about using them than Susan is about using hers, which doubtless disturbs her.

You know what annoys me about how this scene plays out in the movie? Unlike in the book, the beavers don’t get any presents. They’re the ones who have been denied Christmas for most of their lives, not the humans! C. S. Lewis had Father Christmas’s gift to Mr. Beaver be to repair his not quite finished house and his gift to Mrs. Beaver be a new and better sewing machine to replace the one she was worried about the White Witch ruining. (See why that should have been kept?) An earlier draft of the screenplay alluded to these gifts without specifying what they were but, alas, that bit didn’t survive the editing process.

“Now I must be off,” says Father Christmas, putting the sack back in his sleigh. “Winter is almost over and things do pile up when you’ve been gone a hundred years. Long live Aslan and merry Christmas!” As he drives off, everybody waves and calls, “merry Christmas,” after him. “Told you he was real,” Lucy says to Susan. I feel like eight is a bit old to still believe in Father Christmas but it’s a funny line. Despite my various nitpicks, I really am grateful this scene wasn’t scrapped from the movie for fear of being too cute. The joy of it makes a nice break from what is tense, dramatic part of the story.

Speaking of tension and drama…

“He said winter was almost over,” muses Peter. “You know what that means,” he says to his sisters, “no more ice.” We cut to the frozen river they’re supposed to cross, which is not looking so very frozen anymore.

I can resign myself to an adaptation adding an action scene to this part of the story. I don’t love the idea, but I don’t passionately despise it either. However, from when I first heard the specific idea for this action scene, I thought it didn’t make sense thematically since the melting of snow and ice is supposed to be a good thing in the story. The book at this point states that they couldn’t have kept to the river valley because it was flooded with melting snow, but that didn’t matter since the Witch could no longer pursue them in her sleigh and they could afford to take their time.[8]The 1979 cartoon would also add an action scene at this point with the Witch’s sleigh almost catching up to the characters. But in that one, the coming of spring would save the day as it slowed … Continue reading Fortunately, when I saw the movie for the first time, I was so caught up in the action that I forgot to worry about thematic considerations. On subsequent viewings, knowing exactly what’s going to happen, I find my mind wandering more. Oh well.

“We need to cross now,” says Peter. Lucy suggests Mr. Beaver make a dam. “I’m not that fast, dear,” he says. I feel like that’s obvious, but I guess they had to point it out to all the little kids watching.

Peter: Come on!

Susan: Wait! Would you just think about this for a minute?

Peter: We don’t have a minute!

Susan: I’m just trying to be realistic.

Peter: No, you’re trying to be smart! As usual!

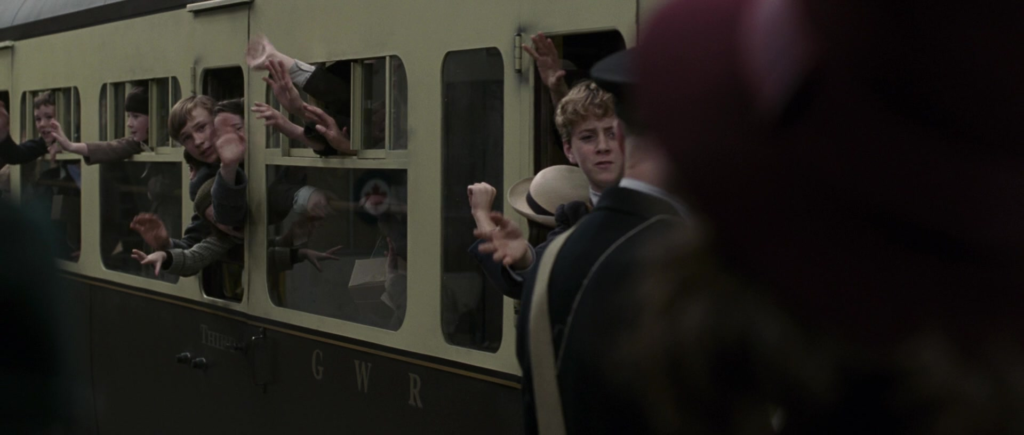

Yeah, this isn’t the most interestingly written scene in the film. The actors do the best they can with the generic dialogue though. Susan receives motivation to follow Peter when she hears wolves howling from not too far away. We briefly cut to the White Witch’s sleigh driving across the same landscape our heroes traversed in the last scene. Back at the river, Mr. Beaver volunteers to be the first one to cross, which doesn’t make much sense since, as a beaver, he presumably weighs less than the humans and wouldn’t be the best test subject but oh well. The ice cracks somewhat as he gingerly makes his way over it. “You’ve been sneaking second helpings, haven’t you,” his wife calls triumphantly. “Well, you never know which meals going to be your last,” he says, “especially with your cooking.” That line annoys me because the book implies that Mrs. Beaver is an excellent cook. I dislike seeing her reputation besmirched for the sake of a middling joke. With the frozen waterfall to their left and the flowing river to their right, the other characters gingerly start to follow Mr. Beaver. The ice cracks under their feet but initially no piece sinks or drifts away until they’re off it. In all fairness, this bit is effectively nerve-wracking. If I sound like I hate the action sequences in this movie, I don’t. It’s just that the scenes that aim for majesty or picturesqueness or childlike awe and wonder in general strike me as not only closer to the original book’s spirit but more memorable as cinema in their own right. This bit is just…fine. “If Mum knew what we were doing,” Susan murmurs. “Mum’s not here!” Peter snaps. The dialogue is again obvious, but I appreciate how it reinforces the theme of the kid characters being thrust into this situation where they have to suddenly be adults.

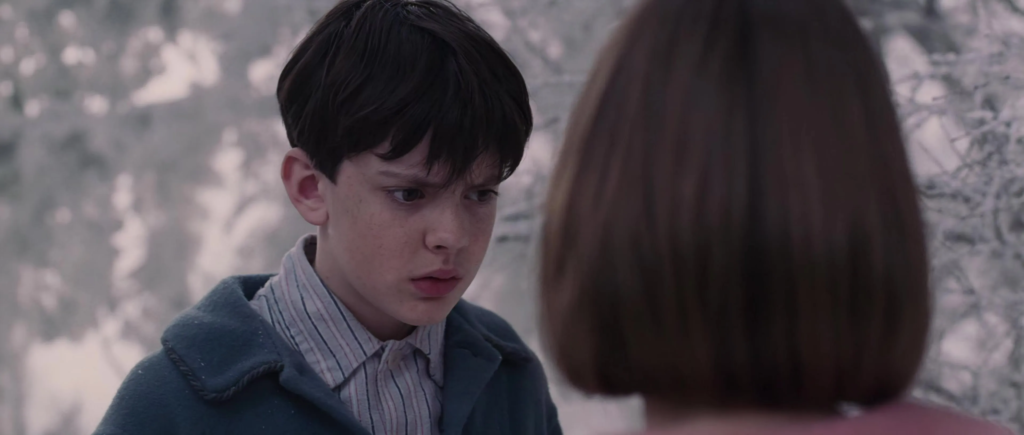

Icicles start to fall from the waterfall. Is it about to completely collapse? No, the wolves are running across it! They jump down and block their prey’s path. Even if running back across the crumbling ice were feasible, more wolves appear behind them. One of the ones in front, not Maugrim, grabs Mr. Beaver by the neck. Peter unsheathes his new sword and awkwardly points it at Maugrim who says, “put that down, boy. Someone could get hurt.” Do you see what I mean about this character being full of pulpy bad guy cliches? (I apologize for using “pulpy” as a descriptor so much lately. Suggest a better word and I’ll be happy to use it for variety.)

Mr. Beaver: Don’t worry about me! Run him through!

Maugrim: Leave now while you can, and your brother leaves with you.

Susan: Stop, Peter! Maybe we should listen to him.

Maugrim (chuckling): Smart girl.

Mr. Beaver: Don’t listen to him! Kill him! Kill him now!

Maugrim: Oh, come on! This isn’t your war. All my queen wants is for you to take your family and go.

Susan: Look, just because some man in a red coat hands you a sword, it doesn’t make you a hero! Just drop it!

Mr. Beaver: No, Peter! Narnia needs you! Gut him while you still have a chance!

Maugrim: What’s it going to be, son of Adam? I won’t wait forever. And neither will the river.

OK, there are a number of things this dialogue is doing or trying to do. One of them is to try to build enmity between Peter and Maugrim so that when the former later kills the latter, it will be a more satisfying moment. (In the book, that was the only chapter that really focused on Peter’s coming of age, which the movie wants to be, more or less, the emotional center of the story.) On that level, it works.

Another thing it wants to do is present Peter with a dilemma. Should he listen to the wolf and possibly save Edmund or not? That part of the scene is pretty dumb since, unlike the White Witch when she first met Edmund, Maugrim is transparently villainous and there’s no reason to believe he would just release Edmund and let all the Pevensies go if Peter were to put down his weapon. In fact, there’s a good argument to be made that it’s ridiculously out of character for the sensible Susan to fall for Maugrim’s obvious lies. I’d make the counterargument that while the character of Susan is supposed to be pragmatic, she’s also supposed to be a bit of a coward. (No offense meant. I’m a bit of one too.) I can buy that with all the stress she’s under that she’d panic and temporarily lose her normal good sense even though I don’t love how that plays out here.

Another thing this scene is doing or trying to do is to give voice to all the contradictory thoughts and impulses going through Peter’s mind without him actually saying anything. Susan and Maugrim are voicing his doubts and insecurities as well as the obligation he feels to his family while Mr. Beaver is voicing the other obligation he feels to fulfill the prophecy and save Narnia. That aspect of the scene strikes me as somewhat annoyingly heavy handed. But you could argue that’s the point. The viewer maybe feels overwhelmed by the lack of subtlety just as Peter feels overwhelmed by his high-pressure situation.

Water starts to spurt out of the waterfall. The long-frozen icicles tremble. But Peter gets an idea. “Hold on to me!” he cries to the girls. They do so as he plunges his sword, not into Maugrim, but into the ice directly in front of him. The ice above collapses and all the characters are engulfed by water.

I’ve got to say it was a shocking decision on the movie’s part to kill off Peter, Susan, Lucy and the beavers here. Definitely a change from the book and not what you’d expect from a children’s movie, but I think it works.

Just kidding! After a moment of silence, a chunk of ice surfaces on the river with Peter, Susan and Lucy clinging to Peter’s sword which still sticks out of it. How did he know the sword wouldn’t split the ice apart? Or that the chunk around it would be big enough to support them all? I don’t know. This is one of those scenes that rewards not thinking about it. Fortunately, if I like a movie and it needs me to not think about it, I’m willing to not think about it. But since I’m doing this lengthy in-depth analysis, I suppose I must. I guess you could say Peter was trapped in any case and this idea was worth a shot.

As the ice floats downstream, Lucy almost slips off, but Peter grabs her shoulder, almost losing hold of his sword in the process. The beavers, who naturally can swim in the cold water, reappear and push the ice toward the shore, allowing the Pevensies to climb off it. But then Peter realizes that he’s not clutching Lucy but only her coat. “What have you done?” screams Susan. We get a shot of the icy rushing river.

Oh, poor Lucy! She was so young, so innocent, so…no, it’s another fake out. Lucy is elsewhere on shore, looking for her coat. Peter just hands it to her, too overjoyed for words. “Don’t worry, dear, your brother’s got you well looked after,” says Mr. Beaver. “And I don’t think you’ll be needing those coats anymore,” says Mrs. Beaver. As the characters pass some frozen trees, we see the frost on them melt and buds start to blossom. Then we cut to later when the previously snowy wood is almost entirely green, more flowers are blossoming in fast motion and Peter, Susan and Lucy have abandoned their coats. Of course, those coats would have been useless even if it were still winter, considering that they’re now cold and wet. Why aren’t Peter, Susan or Lucy getting hypothermia from their dip in the icy river? Magic, I guess.

Meanwhile the White Witch stands…wait. That’s it? Returning spring to Narnia is one of the story’s main goals and a big part of its appeal to the emotions. This seems like the obvious time to have a montage of the landscape changing from white to brown to green. You can’t say it would have made the movie too slow as we just had a tense action scene. I feel like the film earned the right to stop and smell the roses and some its best scenes are when it does just that.

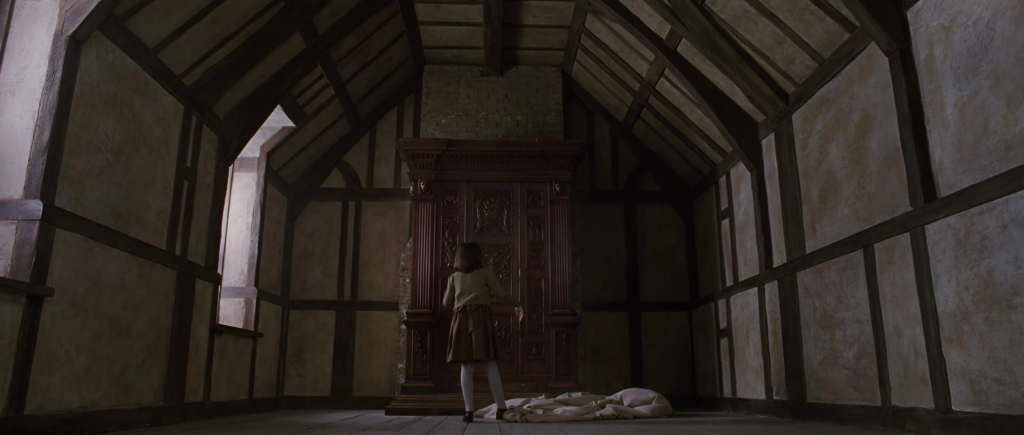

In 2006, an extended cut of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was released. It was a pretty obvious cash grab. The reinstated footage added up to a little more than six extra minutes, mostly consisting of awkward moments that were rightly cut from the theatrical version. But there are a couple of bits that genuinely improve the movie. One of them is the arrival of spring, which is a more drawn-out moment if only by a matter of seconds. They’re seconds well spent. The scenery is lovely, it’s refreshing to see the characters enjoy it, especially Susan the worrywart, and we actually see them passing the hill of the Stone Table. In the book, Aslan’s camp is originally right next to the sacred table, and he later moves it. That would be expensive and time consuming to show in a movie, so the camp is portrayed as removed from the table right from the start. But confusingly, the characters still refer to the camp as being at the Stone Table even though we don’t see it until a later scene somewhere else. This is still a bit confusing in the extended cut but nonetheless relatively easier to parse. Clear exposition sadly isn’t a strength of any of the Narnia movies but that’s less of a problem with this first one then it is with the 2008 Prince Caspian or the 2010 Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

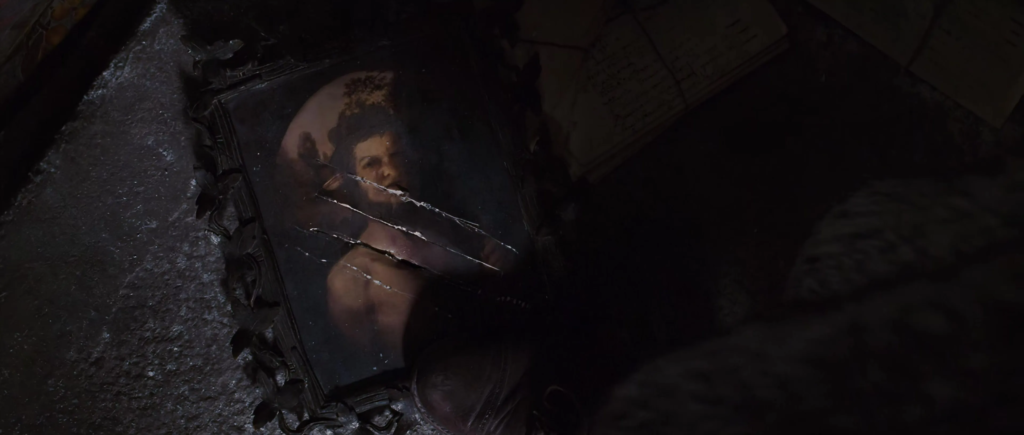

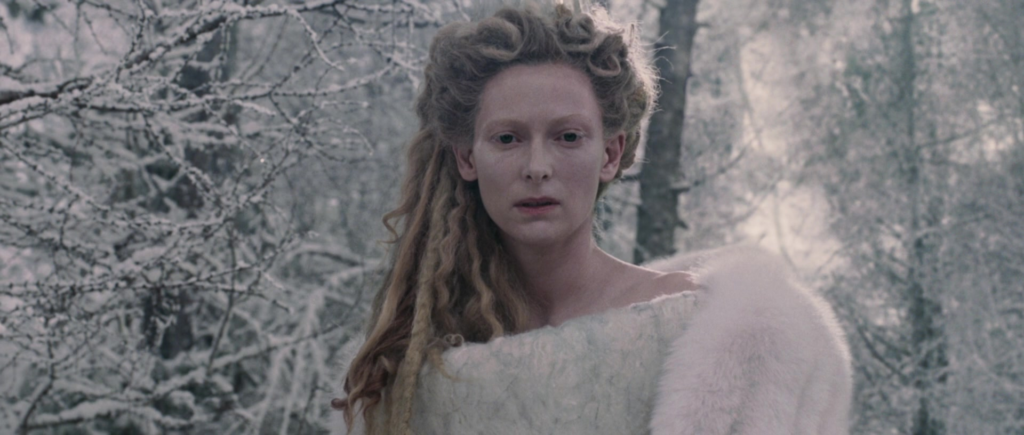

Meanwhile the White Witch stands by the now clear waterfall with Edmund and Ginarrbrik. “It’s so warm out,” says the dwarf as he starts to remove his coat. The Witch gives him a look. While she retains her aloof attitude, she’s clearly furious inside. Ginarrbrik wisely excuses himself to check the sleigh. We see Edmund smile for the first time since he sat on the Witch’s throne. The wolves, who have survived the river, appear with the fox in one of their mouths. “We found the traitor,” one (in the voice of either editor Jim May or fellow editor Sim Evan-Jones; IMDB isn’t clear) says to the Witch, “He was rallying your enemies in the Shuddering Woods.” In the book, the fox or the fox’s dramatic equivalent was caught celebrating Christmas along with some other Narnians. The movie, as I’ve mentioned before, emphasizes military matters over feasting. (I don’t mean that as a criticism, but I don’t mean it as a compliment either.) Shuddering Wood is the name of a location in the Narnia books though so props for that. The wolf drops the fox on the ground. “Ah, nice of you to drop in,” says the Witch. Here is one of the things that makes Tilda Swinton’s performance in this film so great. Given an obvious villainous one-liner like that, she manages to make it sound menacing. “You were so helpful to my wolves last night,” she continues, “Perhaps you can help me now.” The fox hangs his head. “Forgive me, Your Majesty,” he says. “Don’t waste my time with flattery,” says the Witch, sounding pleased, nonetheless. “Not to seem rude,” says the fox, “but I wasn’t actually talking to you.” It’s a great moment. The Witch’s head swerves to look at Edmund and she continues to stare at him in fury as she moves closer to the fox and points her wand at him.

“Where are the humans headed?” she demands. The fox doesn’t look like he’s going to answer. She raises her wand to strike but Edmund suddenly gets between her and her victim. “Wait! No, don’t,” he says, “The beaver said something about the Stone Table and that Aslan had an army there.” The fox shakes his head, but the Witch seems pacified. “Thank you, Edmund,” she says, “I am glad this creature got to see some honesty-before he died!” She touches the fox with her wand and to Edmund’s horror, he turns to stone. The book had mentioned this ability of the Witch’s in the second chapter and the movie had been gradually building up to it, but this moment is the first time in either version that we actually witness her turning someone into a statue and it’s still shocking. She then smacks Edmund’s face and tells him, “Think about whose side you’re on, Edmund, mine or theirs.” The book describes this as the first time in the story that Edmund felt sorry for someone other than himself. That isn’t the case in this movie as we’ve already seen him pity Tumnus, but he still gains more sympathy from the audience.

I’m not sure how Edmund could have had time to hear about Aslan’s army and its location, considering how quickly he got from the beavers’ house to the Witch’s. And I’m not even sure if there was a narrative purpose to him withholding the information from her before, only to spill it now. In the aforementioned earlier draft of the script, Edmund’s well-meaning confession comes before the melting waterfall scene and knowing which direction the other Pevensies are headed is how the wolves are able to catch up with them there. That would have made more storytelling sense, but I do prefer the pacing of the final version. “Gather the faithful,” the Witch instructs her police, “If it’s a war Aslan wants, it’s a war he shall get.” That’s another cliche line that Swinton makes chilling. She’s helped by the fact that as she says it, the Witch randomly zaps a passing butterfly, turning it into stone.

Next Week: We’ve Seen the Wardrobe. We’ve Seen the Witch. Now It’s Time for the Lion.

Bibliography

Lewis, C. S. (1950) The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. HarperCollins Publishers.

Moore, Perry. (2005) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: The Official Illustrated Move Companion. Disney Enterprises Inc.

References

| ↑1 | Actually, it’s more of a brown but whatever. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | They never say his name aloud in the movie, presumably because American kids might not be familiar with it. Not saying the name allows them to assume it’s Santa Claus while English kids can rightly assume it’s FC. |

| ↑3 | The 1979 made-for-TV cartoon did the same thing though weirdly they still had another character refer to Father Christmas. Were they speaking literally or metaphorically? |

| ↑4 | And, hey, it’s not like Lewis specifically wrote that he wasn’t a Norse warrior. |

| ↑5 | Well, actually he was just as big of a hero in the book, but the book wasn’t particularly interested in his heroism. |

| ↑6 | Of course, I understand why writers want to include commentary about issues that are important to them, and I don’t expect them to avoid writing about those issues just to please me. But I don’t feel obliged to enjoy their work either. |

| ↑7 | In the later Narnia books, The Horse and his Boy and The Last Battle, C. S. Lewis would have his heroines, one of them an older Lucy, take part in battles albeit only as archers. This may not have been so much him changing his position as it was him realizing that keeping the girls away from warfare was an impractical rule when he was giving each book at least one point-of-view character who was a girl and giving many of them battles for climaxes. |

| ↑8 | The 1979 cartoon would also add an action scene at this point with the Witch’s sleigh almost catching up to the characters. But in that one, the coming of spring would save the day as it slowed down the sleigh. To be fair, while it seems like a bad thing at the moment, spring will also end up saving the characters by the end of this scene. Sort of. It’s kind of an odd plot point. |