I might have been exaggerating for dramatic effect when I said we were leaving behind the most consistently great part of the movie with the last post in this series. The scene of the Pevensies discovering that Tumnus’s house has been broken into and vandalized some time ago is quite effective in its ominousness.

Edmund accidentally steps on the picture of Tumnus’s father and sees that it’s been slashed. I assume that by having Edmund desperately try to rescue a picture of his father earlier the screenwriters were giving him an extra reason to feel guilty here. That doesn’t really make sense though since there’s no way Ed could know the faun in the picture was Tumnus’s father, let alone that said father was a soldier like his who may very well have died on the battlefield. Oh well. Interesting idea anyway.

Peter finds a note written in a rather jagged, fearsome looking scrawl pinned to the wall and reads it aloud. The language is from the book though somewhat simplified for pacing purposes.

The Faun Tumnus is hereby charged with high reason against her Imperial Majesty, Jadis, Queen of Narnia, for comforting her enemies and fraternizing with humans. Signed: Maugrim, Captain of the Secret Police. Long live the Queen.

Susan: Alright, now we really should go back.

Lucy: But what about Mr. Tumnus?

Susan: He was arrested just for being with a human! I don’t think there’s much we could do.

Lucy: You don’t understand, do you? I’m the human! She must have found out he helped me!

Peter: Maybe we could call the police.

Susan: These are the police.

Peter: Don’t worry, Lu. We’ll think of something.

Edmund: Why? I mean, he’s a criminal!

This is another strong dialogue scene that is true to the characters from the book.[1]Well, except for Peter being a tad more flustered. I especially like the bit about the police, underlining how these kids are used to having adults help solve their problems and now have to solve them on their own, even be pitted against adults. In both the book and the movie, Tumnus’s trashed home and Maugrim’s letter mark a major turning point in the story. While the White Witch has been established as a threat to the characters already, her wickedness has been implied a lot more than shown and we get the impression the story is about to get a lot darker and more suspenseful. All that is well conveyed. Still, as a fan of the literary source material, I have a few nits to pick.

The bigger one is that it’s disappointing that all Edmund says is that Tumnus is a criminal. In the book, he actually makes a reasonable argument to Peter-or a reasonable sounding one anyway, pointing out that they’ve been dropped in a world about which they know nothing, that Tumnus could have been lying to Lucy and the White Witch could very well be a good person for all they know. He’s trying to delude himself, of course, since he wants her to have been the telling the truth to him about a crown and unlimited Turkish Delight. But readers can understand how he could delude himself and maybe even imagine themselves thinking along the same lines if they were in his situation. It’s regrettable that the movie cuts most of this in the interests of tighter pacing.

Another omission is that while Susan does immediately advocate going home after hearing Maugrim’s note in the book, she changes her tune shortly after though with reluctance.

“I’ve a horrid feeling that Lu is right,” said Susan. “I don’t want to go a step further and I wish we’d never come. But I think we must try to do something for Mr. Whatever-his-name is — I mean the Faun.”

This arguably makes her a more nuanced, interesting character than in the movie. Of course, the cinematic Susan will eventually come around to her literary counterpart’s perspective after she undergoes some development. In the book, while character development was implied for all the Pevensies, Edmund was the only one with a real arc and even with him much of it was offstage. The movie, as we’ll see, tries to give each of its leads a significant character arc except for Lucy and she has so many dramatic moments that it’s easy to forget she doesn’t technically have much character development. And to the film’s credit, I think Susan’s character arc is one of its best.

Anyway, the Pevensies hear a voice saying, “psst,” from outside. They glance out the door and see a robin, the first bird we’ve seen in Narnia, hopping up and down on a tree branch, chirping and seemingly beckoning to them. “Did that bird just psst us?” asks a bewildered Susan. They step outside and the robin flies away. In the book, the robin actually leads them quite some distance from the house before flying off, so distant in fact that they realize they’ve gotten lost. In the movie, it’s not even clear if the robin really was trying to communicate with them or if they just imagined it. Still, I’m glad the robin got a cameo in this adaptation since most leave it out and it’s very memorable in the book.

The Pevensies hear a twig cracking behind some rocks and the mysterious voice going, “psst,” again. Peter, Susan and Lucy draw closer together for protection, but Edmund doesn’t. This whole section of the movie does a great job visually portraying his isolation from his siblings. As with the reveal of Mr. Tumnus earlier, I feel like the music takes on a slightly over-the-top quality that gives away that this tense moment is building up to a comedic anticlimax.[2]Well, it’s not an anticlimax in that what the characters are hearing is a big deal but it’s not something scary. What emerges from behind the rocks turns out to be a beaver. Peter bends down and extends his hand, going, “here, boy, here, boy.” The beaver stares at the hand before saying (in Ray Winstone’s voice), “Well, I ain’t going to smell it if that’s what you want!” I’m not a fan of this moment because in the Narnia books, C. S. Lewis states that talking animals[3]He typically refers to them as talking beasts. can be told apart from dumb ones just by looking at their faces. Also, I’m not really sure if someone encountering a beaver in the wild would try call them like a dog or a cat. I mean, beavers aren’t as dangerous as wolverines or anything but they’re still wild animals. That being said, the contrast between the siblings’ different reactions to this reveal, with Edmund and Susan looking terror-stricken, Peter being embarrassed and Lucy just laughing, are pretty funny.

And it’s worth remembering this adaptation’s historical context and appreciating the animation of Mr. Beaver, as this character is called, and the story’s other talking animals. Previous adaptations could only have human actors in costume which didn’t really capture the Lewis’s depictions of them. While the CGI for the animal characters isn’t as convincing as that of Tumnus’s legs, I actually think they look more real than a lot of other CGI characters in modern family popcorn movies.[4]I sometimes get the impression that modern moviemakers have just given up on making computer animated elements in their fantasies look real and solid. I’m so glad the first Narnia was made … Continue reading By the way, the book implies (and all but states) that the talking beavers are as big or bigger than the children. This is consistent with how talking beasts are portrayed throughout the Narnia books, but the movie was probably wise to have them be the size of regular beavers. They’d likely have looked terrifying otherwise.

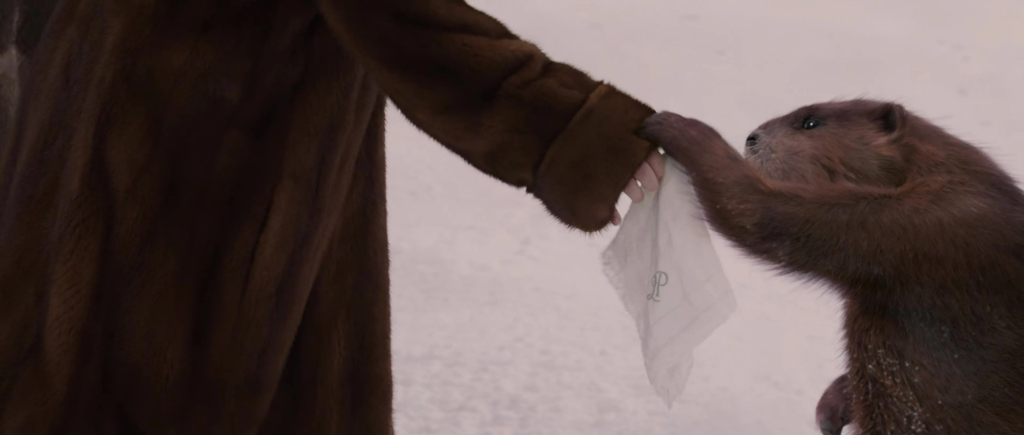

Lucy stops laughing when the beaver calls her by name. He sadly hands her a familiar looking piece of cloth.

It’s the handkerchief she gave to Mr. Tumnus. “He got it to me just before they took him,” Mr. Beaver explains. “Is he all right?” asks Lucy. Mr. Beaver looks around warily. “Further in,” he says and hurries into the woods. Peter and Lucy automatically start to follow him. But Susan grabs them. “What are you doing?!” she asks in a muffled shriek.

Edmund: She’s right! How do we know we can trust him?

Peter: He said he knows the faun.

Susan: He’s a beaver! He shouldn’t be saying anything! Mr. Beaver: Everything all right?

Peter: Yes, we were just talking.

Mr. Beaver: That’s better left for safer quarters.

Lucy: He means the trees.

After exchanging helpless glances with Susan, Peter, along with Lucy, follows Mr. Beaver. The other two Pevensies reluctantly. As the sun sets, they arrive at Mr. Beaver’s house which sits atop a dam he’s built across a frozen river.

We’ve now come to a rare instance of the movie improving on the book’s writing. In response to the sight of smoke coming from his chimney, Mr. Beaver says, “Looks like the old girl’s got the kettle on, a nice cup of Rosie Lee,” which conveys more personality than just “it looks as if Mrs. Beaver is expecting us.” Then we get some dialogue similar to the book though not exactly the same. Lucy compliments Mr. Beaver on his home[5]It’s Susan who does so in the book by the way. and he says, “Oh, it’s merely a trifle, you know. Still plenty to do, ain’t quite finished it yet. But it’ll look a business when it is done.”[6]In the book, he just says, “Merely a trifle! Merely a trifle! And it isn’t really finished!” Mrs. Beaver (voiced by Dawn French) can be heard inside the house, saying, “Beaver, is that you? I’ve been worried sick! If I find you’ve been out with Badger again…” Her voice trails off as she comes outside and sees her human guests. “Oh,” she gasps, “those aren’t badgers. Oh, to think that I should live to see this day!” Then she turns on her husband. “Look at my fur! You couldn’t have given me ten minutes’ warning?” To which Mr. Beaver replies, “I’d have given you a week if I’d thought it would have helped.”

OK, let’s get this out of the way. I’m not a big fan of how the beavers are written in this movie. They’re the main comic relief, which is a bit of a stretch from their counterparts in the book, but I don’t hate the idea in the theory. After all, the literary Mrs. Beaver does have one hilarious line in the scene of her preparing to flee her home and a couple of fairly funny lines elsewhere. And what with the dramatic stakes having been upped and the characters about to be given their main goal, it does feel like the right time in the story to introduce new comedic supporting characters. I guess my problem is how cliche the comedy feels with the beavers being written like a stock old married couple. On reflection however, C. S. Lewis also wrote the beavers like a stock old married couple. (One of Mrs. Beaver’s humorous lines in the book is saying that Peter and her husband are acting “just like men” in letting the tea get old while discussing weaponry.) I guess my problem is that while the Narnia books do contain stock jokes about stereotypical married couples, etc., they also often display a more distinctive style of humor. (The wonderful character of Puddleglum in The Silver Chair with his weird combination of optimism and pessimism is the probably the greatest example of this.) This movie’s humor, on the other hand, even when it’s really, really funny, is basically all generic movie humor. And even when C. S. Lewis was making stock jokes in the Narnia books, they were still really funny. The bickering of the film’s beavers isn’t horribly unfunny or anything but neither does it bring the house down.[7]From what I remember of the filmmakers’ audio commentary, part of the director’s reasoning behind playing the beavers so much for laughs was to get around viewers’ potential … Continue reading

Having said all that, I really do love the casting of their voice actors. I know that may sound strange in the case of Dawn French since she’s primarily a comic performer and I’ve just criticized the beavers’ comedy. But it’s arguably more important to have a hilarious performer when the writing for a humorous character isn’t all that hilarious and French. I also don’t feel like the quality of her line readings drops whenever Mrs. Beaver gets a serious moment, not noticeably so anyway.[8]OK, French doesn’t give the most harrowing emotional performance ever or anything but it’s not like the movie was meant to be Schindler’s List with beavers.

The Pevensies find the beavers’ banter funnier than I do except for Edmund who remains sullen and suspicious as ever. Mrs. Beaver invites them inside for “some food and some civilized company,” the implication being she doesn’t consider her husband civilized. In a nice touch, Susan finds it easier to trust the practical, motherly Mrs. Beaver who is kind of her furry soul sister. She, Peter and Susan follow her into the house, but Edmund lingers outside. He’s noticed that the two hills the White Witch pointed out to him are within walking distance. “Enjoying the scenery, are we?” Mr. Beaver says, eyeing him suspiciously. Edmund doesn’t reply but silently goes into the house. This is a great moment original to the movie that establishes Mr. Beaver suspects Edmund’s treacherousness beforehand rather than just having him say he always suspected it after the fact as in the book.

Peter, Susan and Lucy are seated around the beavers’ dinner table while Edmund sits apart as usual. I’ve got to say the set design for this house is rather disappointing. It’s true that C. S. Lewis describes the pragmatic beavers’ abode as more practical than Tumnus’s, with no books or pictures, but his description also made it just as picturesque in its own way. You’d never guess that from this adaptation. Did the movie have to make everything inside the color brown? Maybe the problem isn’t so much the design as the pacing. This scene doesn’t really give us a good chance to look around the way we had with Tumnus’s cave.

“Isn’t there anything we can do to help Tumnus?” Peter asks. “They’ll have taken him to the Witch’s house,” explains Mr. Beaver, “and you know what they say. There’s few that go through them gates that come out again.” Mrs. Beaver, fearing that Lucy might be saddened by this news, rushes over with a plate of refreshment. “Fish and chips?” she says, proffering what appears to be fish garnished with woodchips. This may be a very brief moment, but it really irritates me. The book lovingly describes the meal of creamy milk, potatoes with “deep yellow butter,” freshwater fish and “a great and gloriously sticky marmalade roll” that the beavers give their human guests. The descriptions of food in the Narnia books are arguably a big part of their appeal and I resent this adaptation changing that for the sake of a pun and not even a particularly funny pun.

“There is hope, dear lots of hope,” Mrs. Beaver tells Lucy, referring to Tumnus’s fate, not the quality of the food. “Oy! We’ve got a right bit more than hope,” says Mr. Beaver. Then, leaning forward and lowering his voice, he says, “Aslan is on the move.” Now we come to one of the most memorable and lyrical bits of the book that is sadly kind of unfilmable.

None of the children knew who Aslan was any more than you do; but the moment the Beaver had spoken these words everyone felt quite different. Perhaps it has sometimes happened to you in a dream that someone says something which you don’t understand but in the dream, it feels as if it had some enormous meaning — either a terrifying one which turns the whole dream into a nightmare or else a lovely meaning too lovely to put into words, which makes the dream so beautiful that you remember it all your life and are always wishing you could get into that dream again. It was like that now. At the name of Aslan each one of the children felt something jump in its inside. Edmund felt a sensation of mysterious horror. Peter felt suddenly brave and adventurous. Susan felt as if some delicious smell or some delightful strain of music had just floated by her. And Lucy got the feeling you have when you wake up in the morning and realize that it is the beginning of the holidays or the beginning of summer.[9]This actually takes place before they go to the beaver’s house in the book and it’s implied to be part of why Peter, Susan and Lucy trust him while Edmund still does not.

The only way the movie could indicate emotions that specific would be to have each character say something like, “Wow! I don’t know why but when you said that name, I felt suddenly brave, etc.” And that could easily come across as clunky. Instead, the camera pans across each Pevensie’s face as music plays. Except for Edmund, each one instinctively smiles. I think that’s what they’re supposed to be doing anyway. But as much as I love William Moseley’s, Anna Popplewell’s and Georgie Henley’s performances in this film, their facial expressions just aren’t interesting in this moment. And while Skandar Keynes’s Edmund looks suitably wary at the mention of Aslan, that’s how he’s looked for several scenes now, so it doesn’t stand out much.

“Who’s Aslan?” he asks. Mr. Beaver laughs, assuming he’s joking, which doesn’t endear him to the boy. He’s astonished to realize the Pevensies really have never heard of Aslan. “He’s only the lord of the whole wood,” he says, “the top geezer, the real King of Narnia.” As a fan, I cringe at that “top geezer” line, given with what reverence the character of Aslan is described the beavers in the book. To the movie’s credit, I think the line may have been improvised by Ray Winstone. To the movie’s discredit, the improv could have easily been cut out and wasn’t. I do like the way Edmund frowns at hearing Aslan described as Narnia’s king since he’s after that title himself. “He’s been away for a long while,” says Mrs. Beaver. Remember what I wrote about Dawn French doing a good job with her character’s dramatic lines considering she’s mainly known as a comic performer? Well, that line is a good example. You really do get an impression from her voice that the citizens of Narnia have been regretting Aslan’s absence and yearning for his return for quite some time. “But he’s just got back,” Mr. Beaver explains excitedly, “and he’s waiting for you at the Stone Table!” Susan expresses surprise that someone important would be waiting for them specifically.

Mr. Beaver: You’re blooming joking! (to his wife) They don’t even know about the prophecy!

Mrs. Beaver: Well then?

Mr. Beaver: Look. Aslan’s return. Tumnus’s arrest. The Secret Police. It’s all happening because of you!

Susan: You’re blaming us?

Mrs. Beaver: No, not blaming! Thanking you!

If Mr. Beaver didn’t want that to sound like blame, maybe he shouldn’t have said it in such an angry voice. I’m kind of with Susan here. Anyway, Mr. Beaver explains that there’s a prophecy in Narnia.

When Adam’s flesh and Adam’s bone

Sits at Cair Paravel in throne,

The evil time will be over and done.

“You know, that doesn’t really rhyme,” says Susan. “Yeah, I know it doesn’t but you’re kind of missing the point,” protests Mr. Beaver. There are Narnia fans out there, many of them perhaps, who cringe at that “doesn’t really rhyme” line as much as I cringe at the “fish and chips” and the “top geezer” lines since it amounts to a joke at the original book’s expense. But I don’t cringe. Actually, it really makes me laugh. Maybe it’s because Anna Popplewell has great comedic timing. Maybe it’s because I hate eye rhymes. For me, it’s one of the movie’s best jokes.[10]As a poet, I would describe C. S. Lewis as a marvelous prose writer. Returning to the scene, “It has long been foretold,” says Mrs. Beaver, “that two sons of Adam and two daughters of Eve will defeat the White Witch and restore peace to Narnia.” In the book, there are actually two (sort of) rhyming prophecies, one about the children and another about Aslan.

Wrong will be right, when Aslan comes in sight,

At the sound of his roar, sorrows will be no more,

When he bares his teeth, winter meets its death,

And when he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again.

And the one about Aslan is actually treated as more important with Mr. Beaver mentioning the one about the Pevensies and Castle Cair Paravel almost as an afterthought. (“The quickest way you can help (Mr. Tumnus) is by going to meet Aslan. Once he’s with us, then we can begin doing things. Not that we don’t need you too…”) This is problematic for Christian fans of the books as well as non-Christian who really like the character of Aslan since he, corresponding to God, is supposed to be the ultimate hero. For what it’s worth though, you could argue that the fact that Aslan is God makes it self-explanatory why his return to Narnia would be a big deal and if the movie had to cut one of the prophecies, it was more important to retain the one explaining why four random kids coming to Narnia would be a big deal. “And you think we’re the ones?” says Peter. “Well, you’d better be,” says Mr. Beaver, “because Aslan’s already fitted out your army!” The book actually doesn’t mention that Aslan has any army until we actually meet them. As we’ll see, the movie really expands on the military aspect of the story. I’m not overjoyed about this since movies about war don’t interest me much but, to be fair, it’s not like there was no military aspect in the original book at all and a few of the other Narnia books have an even greater one.

Susan reminds Peter that the whole reason they were sent away from London was to avoid war. (You’ve got to love that bit of irony.) “I think you’ve made a mistake. We’re not heroes,” Peter apologetically tells the beavers. “We’re from Finchley,” adds Susan as if that inherently disqualifies them. (I’m not saying that to poke fun at the movie. I think the movie itself is poking fun at Susan.) She thanks the beavers for their hospitality in what C. S. Lewis would have described as “her most annoying grownup voice” but insists that she and her siblings have to go now. “You can’t just leave,” protests Mr. Beaver. “He’s right,” says Lucy, “we have to help Mr. Tumnus.” This is probably the biggest change the movie makes to the book’s story. The literary Pevensies never really express any enthusiasm about being the ones to save Narnia, but they don’t really question why it should be them or try to back out of it either. Truth be told from here on in the book, Lewis treats Peter, Susan and Lucy like chess pieces and doesn’t give them much in the way of inner lives. That never bugs me when I read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe but I can theoretically understand the screenwriters feeling like it was a flaw. I wouldn’t say the fairly standard reluctant hero arc they gave the characters, mainly Peter, was necessarily the best or the only way to fix that though. Still, it’s not a bad standard reluctant hero arc either. Some of it is quite touching.[11]And if the word, standard, sounds too judgmental, I’ll readily allow that there were plots and characters in the Narnia books that were also stock plots and characters. Those just aren’t … Continue reading Peter and Susan are a lot more likeable here than some reluctant heroes. They don’t act annoyed by the beavers or anything[12]Well, maybe Susan does a little but that feels broadly true to the character from the book series as a whole. and since they don’t have any obvious superpowers, it makes perfect sense that they wouldn’t believe they could help save Narnia.

I also don’t feel like Peter’s feelings of fear and uncertainty in the movie are that much of a stretch from the book’s character. When he’s called upon to rescue one of his sisters in a later scene, Lewis writes that “Peter did not feel very brave; indeed, he felt he was going to be sick. But that made no difference to what he had to do.” Doing the brave and honorable thing despite fear is a minor theme in the book, as we saw earlier with the Pevensies deciding whether to try to help Tumnus or go back to their own world, one on which the movie expands, not something it pulls out of nowhere. It’s also worth noting that other good kings in the Narnia books express a sense of unworthiness when offered the role so this really doesn’t feel untrue to the books’ portrayal of leadership to me. And Lucy being the only sibling to instantly accept the Call to Adventure feels true to her role in the books too.

It’s possible, maybe even likely, that part of the motivation for this change on the part of the filmmakers is that they weren’t comfortable with the idea of the Pevensies deserving the roles of kings and queen just by virtue of being human and prophesied and especially with the idea of Peter deserving the role of high king just by virtue of being firstborn. Having the characters themselves question that was a way of making them more relatable from their point of view. You can definitely argue that C. S. Lewis was too enamored of the idea of natural hierarchies himself to convey their romantic appeal to anyone who didn’t already share his feelings.[13]Though the Narnia books certainly don’t suffer from this anywhere near as much as That Hideous Strength does. You can also definitely argue that modern screenwriters are too skeptical about the idea of natural hierarchies and that their fantasies would be better if they just relax and accept them, if only for the sake of their stories. I can see both sides. There’s a school modern criticism that is skeptical of the whole idea of prophesied heroes, seeing them as lazy storytelling. I sympathize with this criticism, but I also think prophesied heroes have a poetic appeal into which both versions of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the movie and the book, tap.[14]In The Horse and his Boy, Lewis uses the prophesied hero trope with the twist that neither the reader nor the hero himself learn about the prophecy until after it’s been fulfilled.

While I’ll defend this added character arc on the whole, I have to admit that it comes with some major downsides. Having Peter initially refuse to go to the Stone Table means cutting one of his most memorable lines of dialogue in the book, where he tells the beavers that he’s longing to see Aslan “even if I do feel frightened when it comes to the point.” The reason he might feel frightened is that in Mrs. Beaver’s words, “If there’s anyone who can appear before Aslan without their knees knocking, they’re either braver than most or else just silly.” In arguably the book’s most memorable line which is totally absent from the movie’s version of this scene, Mr. Beaver says that Aslan isn’t safe, but he is good. Thankfully, the movie will give us a version of that line towards the end, and it will be a nice moment though you could argue the movie won’t have Aslan scary enough for it to really make sense. Then again, you could say the same of the book. (Aslan’s scariness there is less about anything he does than it is the atmosphere his presence creates. More on this later.) Of course, there’s no reason the movie couldn’t have used the line both in this scene and towards the end. It’s not like the screenwriters are averse to callbacks. Another omission I consider unfortunate is not clarifying that Aslan is the one being (or possibly one of very few beings) that the White Witch can’t turn into stone. Without that established, it’s unclear why she doesn’t just do that and solve her main problem. Then again, this version of the story hasn’t established that she can turn anyone into stone yet.

Phew! Where we in the plot again? Oh yeah. Peter tells Lucy that there’s nothing they can do and that it’s time for them to go. He then turns around to see that Edmund has mysteriously disappeared.

“I’m going to kill him!” he grumbles. “You may not have to,” says Mr. Beaver ominously. “Has Edmund ever been to Narnia before?” We cut to Edmund making his way through the snow. As in the book, he’s left behind his coat but isn’t going back for it.

Mr. Beaver and the Pevensies are on his trail. They come to a stop when they see the White Witch’s house in the distance and Edmund about to enter it. I’m not a fan of the movie decision to have the Witch’s castle be made out of ice. It strikes me as obvious and cliche for this kind of villain. I’d have preferred a stone fortress like in the book. That would have been grimmer and fit in with her turning her enemies into stone statues. Stone also has certain grim connotations that ice doesn’t. After all, the latter melts and the former doesn’t. (I guess making her home out of ice is supposed to be a boast on the Witch’s part. “I don’t need to worry about it melting because my winter will never end!”) Even if the house had to be made of ice, I don’t love the design which looks more like a bunch of pointy ice shards stuck together than a building in which one could actually live. But, while it may lack grimness, the eerie light coming from the Witch’s house does allow the characters to get a good look at Edmund.

In the book, of course, the Pevensies don’t actually see him do this. Mr. Beaver just explains to them that he’s doing it. I actually love this change on the movie’s part. True, it’s questionable how the characters could run all the way to the Witch’s house, run back to the beavers’ house, pack and then flee before her police caught up with them,[15]Actually, they don’t do that as we’ll see. but this way it feels a lot more credible that they would take Mr. Beaver’s word that their own brother could betray them and the visual of them watching Edmund, helpless to stop him, packs a real emotional punch. Lucy tries calling to him, but Mr. Beaver shushes her. Biting his lip, Peter starts to run after Ed, but Mr. Beaver stops him.

Susan: We can’t just let him go!

Lucy: He’s our brother!

Mr. Beaver: He’s the bait! The Witch wants all four of you!

Peter: Why?

Mr. Beaver: To stop the prophecy from coming true! To kill you!

They look back at the castle in time see the gates closing behind Edmund as he passes through them.

Susan lashes out at Peter. “This is all your fault!” she says. “None of this would have happened if you’d just listened to me in the first place!” I know there are some fans of the book’s characters who feel the movie sullies them by having them fight with each other too much. I guess this is an example of that, but I don’t really mind. After all, around this point in the book, Susan does say, “Oh, how I wish we’d never come,” which isn’t really an I-told-you-so line but, given her early suggestions that they leave, isn’t very far from it. And, given the characters’ terrible situation, it feels believable to me that they would panic and turn on each other this way. Peter and Susan look like they’re about to get into a really nasty tiff when Lucy interrupts them. “Stop it!” she says. “This isn’t going to help Edmund.” I love the irony of Lucy the youngest pointing this out rather than the older, more pragmatic and ostensibly more mature Susan. “She’s right. Only Aslan can help your brother now,” says Mr. Beaver. “Then take us to him,” says Peter before giving the Witch’s house one last look.

Next Week: Remember That Captain of the Secret Police Who Arrested Mr. Tumnus? We Meet Him.

References

| ↑1 | Well, except for Peter being a tad more flustered. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Well, it’s not an anticlimax in that what the characters are hearing is a big deal but it’s not something scary. |

| ↑3 | He typically refers to them as talking beasts. |

| ↑4 | I sometimes get the impression that modern moviemakers have just given up on making computer animated elements in their fantasies look real and solid. I’m so glad the first Narnia was made before that trend. |

| ↑5 | It’s Susan who does so in the book by the way. |

| ↑6 | In the book, he just says, “Merely a trifle! Merely a trifle! And it isn’t really finished!” |

| ↑7 | From what I remember of the filmmakers’ audio commentary, part of the director’s reasoning behind playing the beavers so much for laughs was to get around viewers’ potential discomfort with talking animals. I don’t understand this as most cultures tell stories about animals that talk. There are probably more people familiar with the concept of them than there are with fauns. |

| ↑8 | OK, French doesn’t give the most harrowing emotional performance ever or anything but it’s not like the movie was meant to be Schindler’s List with beavers. |

| ↑9 | This actually takes place before they go to the beaver’s house in the book and it’s implied to be part of why Peter, Susan and Lucy trust him while Edmund still does not. |

| ↑10 | As a poet, I would describe C. S. Lewis as a marvelous prose writer. |

| ↑11 | And if the word, standard, sounds too judgmental, I’ll readily allow that there were plots and characters in the Narnia books that were also stock plots and characters. Those just aren’t as noticeable nowadays because they’re using older storytelling conventions. |

| ↑12 | Well, maybe Susan does a little but that feels broadly true to the character from the book series as a whole. |

| ↑13 | Though the Narnia books certainly don’t suffer from this anywhere near as much as That Hideous Strength does. |

| ↑14 | In The Horse and his Boy, Lewis uses the prophesied hero trope with the twist that neither the reader nor the hero himself learn about the prophecy until after it’s been fulfilled. |

| ↑15 | Actually, they don’t do that as we’ll see. |