Remember how at the end of Part 4, I wrote that we’d reached a place where I felt the movie’s quality, the quality of its writing anyway, started to go downhill? Well, I’m happy to report that we’ve now reached a point where it starts going uphill again. I’m not sure if it’s as consistently great as it was before, at least from an adaptation standpoint, but I find it closer than it was during that middle section we just went through, maybe because the characters whose dialogue I enjoy the least talk less.

As Peter, Susan, Lucy and the beavers walk uphill toward Aslan’s camp, we see what appear to be a horse’s hooves. The camera pans up to reveal that the hooves actually belong to a centaur who blows a horn signaling our heroes’ arrival. (By the way, the movie portrays some centaurs as being female even though, like fauns, they’re a one-sex species in mythology.)

I love the colors in this part of the movie! Actually, I love the art direction throughout this whole film, but we’ve reached a turning point of sorts when it comes to the visuals that makes it worth bringing up the topic again. The bright green of the hillside contrasts with the black and white visuals that have defined Narnia up till now. Not that those weren’t beautiful in their own way. Sheesh, I can theoretically understand some viewers finding them easier on the eyes. But in context, they come across as very refreshing. And the bright, almost circus-like colors of the tents make Narnia feel like something out of a storybook. It’s perfect.

Right before the characters enter the camp, Lucy notices a couple of dryads who wave at her. This movie series portrays the dryads’ bodies as being composed of seemingly windblown leaves and flower petals. The book depicts them more as people with bark for skin and leaves, willows and moss for hair and clothing. I’d have preferred something like that, but I don’t dislike these dryads. Actually, I appreciate that they don’t look like the ents in the Lord of the Rings movies, which still loomed high in the public’s memories when this movie was released.

Lucy waves back at the dryads. This moment reminds me of one from another Narnia book, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, where Lucy makes eye contact with a Sea Girl e.g. a mermaid.

Neither could speak to the other and in a moment the Sea Girl dropped astern. But Lucy will never forget her face…Lucy had liked that girl and she felt certain the girl had liked her. In that one moment they had somehow become friends. There does not seem to be much chance of their meeting again in that world or any other. But if ever they do, they will rush together with their hands held out.

As they enter the camp, various Narnian creatures stare at the humans in awe. Susan nervously wonders why, and Lucy suggests she looks as strange to them as they do to her. In another look-they-really-do-love-each-other moment, Mrs. Beaver starts to groom her fur and her husband tells her to stop fussing because she looks lovely. Aslan’s soldiers fall in behind the Pevensies as they approach a big tent in the middle of the camp.

Outside stands a centaur (Patrick Kake.) This character isn’t from the book but he’s true to the Narnia books’ depictions of centaurs in that he’s intimidatingly stern[1]In the book, Prince Caspian, a character says that “no one ever laughed at a centaur., wise and noble though he’s more of a warrior whereas in the books, centaurs are defined more by being astrologers/prophets. His name is Oreius, which sounds like it could easily be a name from the Narnia books, but it should be the name of a faun, not a centaur. (Centaur names in the books include Glenstorm, Cloudbirth and Roonwit. Faun names include Tumnus, Mentius and Obentinus.) Oh well, nice try.

Peter unsheathes his sword and salutes Oreius. “We have come to see Aslan,” he says, his voice trembling. That’s not a criticism of Moseley’s performance. He’s clearly supposed to be nervous.[2]As well he should be. In the book, Mrs. Beaver says, ““if there’s anyone who can appear before Aslan without their knees knocking, they’re either braver than most or else just … Continue reading Oreius turns toward the tent and all the soldiers bow.

A tremolo is then heard on the soundtrack that give me the shivers, more so, regrettably, than the music that plays when the tent flap opens and Aslan (voiced by Liam Neeson), who is here revealed to be a lion, steps out. Peter, Susan and Lucy kneel before him. Now one of the most memorable parts of the book, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and the Narnia books in general is the feeling that Aslan’s presence inspires in all the characters.

People who have not been in Narnia sometimes think that a thing cannot be good and terrible at the same time. If the children had ever thought so, they were cured of it now. For when they tried to look at Aslan’s face they just caught a glimpse of the golden mane and the great, royal, solemn, overwhelming eyes; and then they found they couldn’t look at him and went all trembly.

Every fan hopes seeing Aslan onscreen will give them this feeling. Does it in this movie? Well…for me, not really. To be fair though, I’m not sure how it could. While the fact that Aslan is a lion is certainly part of what makes him “terrible”, it’s not just that.[3]In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, a character who has been transformed into a dragon describes meeting Aslan thus. “I was terribly afraid of it… I could have knocked any lion out easily … Continue reading And while we can theoretically understand why meeting a lion is scary for the characters in the movie, it’s not that scary for us to watch it onscreen, knowing that the lion is a good guy who won’t eat them. Aslan doesn’t really do anything intimidating in this scene in this book. It’s more a matter of his aura, something that might be easier to describe in a book[4]Though even with that medium just saying that someone has an aura can be unconvincing by itself, especially if you lack C. S. Lewis’s eloquence. than to actually generate in a movie.[5]I wouldn’t say it’s impossible for a movie. One I’ve written about on this very blog, The Prince of Egypt, kind of nails the numinous effect which Lewis gave Aslan in its burning … Continue reading I’m not bitter toward the filmmakers for their failure because, while there are things they perhaps could have done better[6]In the book, the characters are in such awe of Aslan, that none of them dares be the first to address him and they get into a little argument over it. Including that might have helped the movie sell … Continue reading, I get the impression from the actors’ performances, from the soundtrack and the general staging that they were trying.

As Aslan’s voice, Liam Neeson is…fine. The fact that his isn’t one of the best vocal performances in the movie actually says great things about the voice acting and acting in general in it. He sounds suitably soothing when comforting the Pevensies and suitably stern when confronting the White Witch. He just isn’t much about which to write home for such a major character. According to the book, Aslan’s voice “was deep and rich and somehow took the fidgets out of (the characters.”) Neeson’s voice isn’t particularly deep, which I think may actually have been a good thing as a deep voice is the obvious route to go with a lion. It also might have worked better for the character though. On the plus side, Neeson’s voice can reasonably be described as rich. Previous actors portraying Aslan have all hammed it up in the role in their own unique ways and there is something refreshing about Neeson’s Aslan not being a ham. I can’t blame those other actors for wanting to ham it up with such a big character, especially the ones in radio dramas which depend almost solely on them to bring that character to life, but hearing a version of Aslan deliver his lines like a normal person does make for a nice change.

The ensuing dialogue is fairly close to the corresponding conversation in the book.

Aslan: Welcome, Peter, Son of Adam. Welcome, Susan and Lucy, Daughters of Eve. And welcome to you, Beavers. You have my thanks. But where is the fourth?

Peter: That’s why we’re here, sir. We need your help.

Susan: We had a little trouble along the way.

Aslan: Captured? How could this happen?

Mr. Beaver (after an awkward pause): He betrayed them, Your Majesty.

Oreius: Then he has betrayed us all!

Aslan: Peace, Oreius. I’m sure there’s an explanation.

This is a minor but, I think, interesting difference between the book and the movie. In the former, Aslan never asks for an explanation for Edmund’s betrayal, not that we learn anyway. (He has a private conversation with Edmund later to which we are not privy.) Lewis just writes that “something made” Peter give a partial explanation anyway. It can be inferred though that Aslan’s presence was that something. Meeting him seems to accelerate character development for each of the Pevensies in both the book and the movie. “It was my fault really,” Peter says at this point in the latter to his sisters’ surprise, “I was too hard on him.” Susan puts a supportive hand on her older brother’s shoulder. “We all were,” she says. That isn’t really true since Susan wasn’t really hard on Edmund that we saw. In fact, you’ll recall that when Peter and Lucy were upbraiding him, she tried to change the subject. But after seeing Peter and Susan butting heads for so much of the movie prior to this moment, it’s very heartwarming. “Sir, he’s our brother,” adds Lucy. “I know, dear one,” says Aslan, “but that only makes the betrayal all the worse.” That’s also a minor but interesting change from the book. Lewis doesn’t have Aslan verbally condemn Edmund here. Neither does he blame Peter or excuse him. He “merely stood looking at him with his great unchanging eyes. And it seemed to all of them that there was nothing to be said.” Again, that’s something that’d be hard to accomplish in a film as opposed to a book. “This may be harder than you think,” says the cinematic Aslan. His literary counterpart says something similar when Lucy asked him if he could save Edmund. According to Lewis, “Up to that moment Lucy had been thinking how royal and strong and peaceful his face looked; now it suddenly came into her head that he looked sad as well.” The movie’s animators capture that well. I think it would have been even more powerful if Aslan’s face had looked sterner before this moment and it’s not like they were incapable of that. His features are quite stern looking in some other scenes. Still, as it is, the movie does a great job with this pivotal scene.

Later, at sunset, Peter stands on a hill overlooking the camp. He has now changed into a Narnian outfit. The book never specifies that he or his brother or sisters do this, but it makes perfect sense, given the state their clothes would realistically be in at this point, and it allows costume designer Isis Mussenden to showcase royal Narnian garb, something Lewis doesn’t describe in great detail but the beauty of which he stresses.[7]He also emphasizes that in Narnia, unlike in our world, fancy clothes are actually comfortable. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? Peter’s Narnian costume isn’t really Mussenden’s best work but don’t worry. We’ll see better examples of it shortly. Aslan comes up behind Peter and points out to him a shining castle on the seacoast in the distance. “That is Cair Paravel, castle of the four thrones on one of which you will sit, Peter, as High King.” Peter doesn’t respond enthusiastically to this. Aslan asks if he doubts the prophecy. “No,” says Peter, “it’s just…it. Aslan, I’m not who you think I am.” To his surprise, the lion responds, “Peter Pevensie, formerly of Finchley. Beaver also mentioned you planned on turning him into a hat.” Some fans may be disappointed in that moment since it seems to imply that Aslan is omniscient-or more “niscient” than your average lion-only to humorously subvert it. In the books, Aslan is meant to be the Christian God who is omniscient but, to be fair, the book version of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe does have moments that imply Aslan isn’t. (He outlines two possible battle plans, one for fighting the White Witch in the forest and one for assaulting her castle if his army can’t cut her off from it and in the same scene, he gets distracted and asks Peter to repeat a question.) But in the very next book in the series, Prince Caspian, he says he’s sometimes wondered if the character of Reepicheep, whom he’s never met face to face, thinks too much about his honor. The plots of The Horse and his Boy and The Silver Chair depend on Aslan, at the very least, being able to accurately predict the future. His lack of omniscience in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is something of an example of Early Installment Weirdness, something of which the book has a fair bit. Of course, the filmmakers clearly did research on the later Narnian installments so maybe I shouldn’t let them off the hook so easily.

“Peter,” Aslan says, “there is a Deep Magic, more powerful than any of us, that rules over all of Narnia. It defines right from wrong and governs all our destinies, yours and mine.” This metaphysical Deep Magic, which corresponds to the Christian concept of God’s Law, is easily one of the weirdest parts of the book, especially as it’s not introduced until the last third of the story and proves integral to it. I understand the screenwriters introducing it a little earlier here, if only by a couple of scenes. I don’t love the way they describe it though. Somehow it sounds vaguely like the Force in Star Wars. Maybe what rubs me the wrong way about the phrasing is that it implies the Deep Magic outranks Aslan. To be fair, that’s not entirely wrong. When someone asks Aslan in the book if he can do anything against the Deep Magic, he responds with grave anger. And in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, when a character expresses incredulity that a magic spell could have the power to make Aslan visible, he says, “Do you think I wouldn’t obey my own rules?” Whether Christians believe God is somehow bound by his law is a tricky question, one I’d prefer these screenwriters not try to answer so glibly. But what I do like about this part of the movie is that we get more subtle foreshadowing that Aslan is planning to do something painful for him. When he talks about having no choice regarding his own destiny, he turns his face away from Peter, hiding a rather sad expression from him.

Peter doesn’t pick up on Aslan’s melancholy. (I don’t mean that as a criticism of the character by the way.) “But I couldn’t even protect my own family,” he protests. “You brought them safely this far,” counters Aslan. “Not all of them,” Peter says wistfully. “Peter, I will do what I can to help your brother,” says Aslan[8]I wish he said, “all I can,” since that’s closer to what he says in the book but that’s a nitpick., “but I need you to consider what I ask of you.” He looks down at his subjects in the camp below. “I too want my family safe.” It’s a moving moment that recalls a scene from another of the Narnia books, The Magician’s Nephew, in which Aslan expresses empathy for a character’s concern for their family but asks them to put it on hold for the sake of Narnia.

We cut to the Witch’s camp where Edmund is gagged and tied to a tree. Ginarrbrik taunts him. “Is our little prince uncomfortable? Does he want his pillow fluffed? Special treatment for the special boy. Isn’t that what you wanted?” This dialogue is no more subtle than that during the melting waterfall scene, but for whatever reason, it works a lot better for me.

Back at Aslan’s camp, Susan and Lucy have been given Narnian dresses that are better examples of Isis Mussenden’s talent than Peter’s outfit and are admiring their reflections in a stream.

Lucy (approvingly): You look like Mum.

Susan: Mum hasn’t had a dress like this since before the war.

Lucy: We should bring her one back! A whole trunkful!

Susan: If we ever get back.

Susan notices Lucy’s face falling at those last words and apologizes. “We used to have fun together, didn’t we?” she says. “Yes,” says Lucy wistfully before adding with a laugh, “before you got boring.” The girls have a splash fight in the stream then they go up the bank to get towels. Susan removes one from a clothesline, only to reveal a snarling Maugrim behind it. “Please don’t try to run,” he says, “we’re tired.”

“And we’d prefer to kill you quickly,” adds another wolf (Jim May.)[9]I’m aware this wolf is called Vardan in the credits, but no one says his name in the film proper, so using it feels weird to me. The movie is in a bit of a tricky spot here. In the book, Peter ends up rushing to his helpless sisters’ rescue and this adaptation doesn’t want to change that. Indeed, it has built up Maugrim as an enemy of Peter specifically in a way the book didn’t. But in this day and age, the trope of a female character needing a male character to save her life has fallen so out of favor as to be offensive. The movie finds a graceful compromise by having Susan need to get past Maugrim to get her magical horn from Father Christmas, which she’s left with her old clothes, and having her hit him with a towel to do so.[10]If you’d like my opinion on the controversy over the Narnia books’ portrayal of gender, here’s the shortest answer I can give. While Lewis did go on record as being antifeminist in … Continue reading Back on the hilltop, Peter and Aslan hear the horn. “Susan!” cries Peter and runs in the direction of the sound. In the book, Aslan had to tell him it was her horn. That would have made more sense, but I understand the movie wanting to tighten the pace of a suspenseful action moment. (I guess we can assume Peter had a general idea of where his sisters were and knew anything like a warning signal from there meant trouble.) Susan and Lucy have climbed into the branches of a tree, but the wolves are snapping at the former’s dangling ankles and those aren’t the thickest branches either. Peter comes running with his sword, yelling, “Get back!” The wolves turn their attention to him.

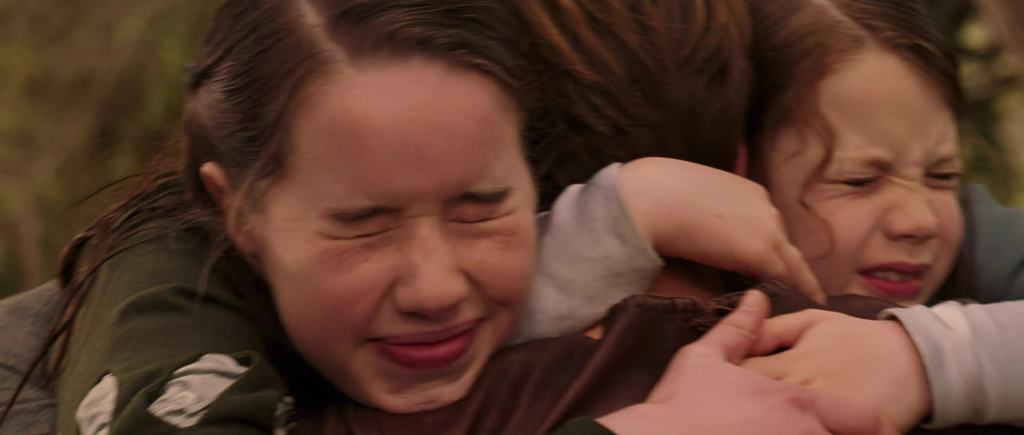

“Come on,” says Maugrim, “we’ve already been through this before. We both know you haven’t got it in you.” Suddenly, Aslan’s clamps down on the non-Maugrim wolf, leveling the playing field for Peter. Oreius and some other soldiers from the camp arrive but Aslan tells them to stay their weapons on the grounds that “this is Peter’s battle.” With one last taunt (“You may think you’re a king but you’re going to die like a dog!”), Maugrim pounces on Peter, knocking him over. The girls scream. Suddenly, both Peter and the wolf lie still. Susan and Lucy leap down and run over. Maugrim is dead with Peter’s sword in his stomach while underneath him, Peter is very much alive. The three Pevensies hug, all of them looking somewhat traumatized, much as the book describes at this point.[11]Well, it describes Peter and Susan as crying. Lucy isn’t the focus as much in this part of the book.

Perhaps surprisingly, given how this adaptation ups the action from the book, this scene isn’t as exciting to watch as its literary equivalent is to read.

(Peter) rushed straight up to the monster and aimed a slash of his sword at its side. That

stroke never reached the Wolf. Quick as lightning it turned round, its eyes flaming, and its mouth wide open in a howl of anger. If it had not been so angry that it simply had to howl it would have got him by the throat at once. As it was — though all this happened too quickly for Peter to think at all — he had just time to duck down and plunge his sword, as hard as he could, between the brute’s forelegs into its heart. Then came a horrible, confused moment like something in a nightmare. He was tugging and pulling, and the Wolf seemed neither alive nor dead, and its bared teeth knocked against his forehead, and everything was blood and heat and hair. A moment later he found that the monster lay dead, and he had drawn his sword out of it and was straightening his back and rubbing the sweat off his face and out of his eyes.

To be fair though, I’m not sure how the film could have captured that intensity except by filming the scene from Peter’s point of view and that might have cost it is PG rating. I think PG was the right rating for this movie to aim. You could argue that the descriptions of violence in the book are technically more gruesome, but I’d describe it as a book that’s good for kids if they have parental supervision and I’d prefer an adaptation’s rating to correspond to that.

Anyway, Aslan lets go of the other wolf who runs away, whimpering. “After him,” says Aslan to Oreius. “He’ll lead you to Edmund.” Oreius and a party of other swift soldiers chase after the wolf. Then Aslan turns his attention back to the Pevensies. “Peter, clean your sword,” he says. In the book, his line is “you have forgotten to clean your sword.” The contrast between the intensity of what just happened, and the mundanity of Aslan’s chiding is pretty funny and I wish the movie could have kept that. We cut to Peter kneeling with his sword now clean and Aslan putting his paw on his shoulder. “Rise, Sir Peter Wolfsbane,” he says, “knight of Narnia.” In the book, he concludes by saying, “And whatever happens, never forget to wipe your sword,” again making this a funny moment.[12]Though it should be noted that for all that Aslan’s words are jarring in their mundanity, keeping your sword clean is important as you don’t want it to rust. Oh well. If the movie had to omit the humor there, it’s a decent enough serious moment.

Night has fallen on the Witch’s camp, and we see some of her monstrous followers preparing weapons. This is a bit of change from the book in which she only summons them after she’s learned of Maugrim’s death. The movie wisely refrains from showing the most gruesome of the creatures until the point the book shows them though. The Witch’s minotaur general (Shane Rangi) is discussing a battle plan with her. I don’t get why the movie has the minotaurs’ bodies be entirely covered with hair. They’re supposed to be like men with the heads of bulls. But to be fair, Narnian minotaurs don’t have to be exactly like classical depictions.

The wolf comes running into camp, followed by Aslan’s rescue party. The Witch and the general go to investigate. They find several of their soldiers dead, Edmund gone and Ginarrbrik gagged and bound in his place. There’s even a knife stuck in his cap! The idea that Oreius and company would have the time to do all that and leave before the Witch and her reinforcements arrived to stop them is pretty ridiculous but the visual is amusing enough that I’ll allow it.[13]In the book, as I mentioned, the Witch’s army hadn’t arrived yet and one of Aslan’s soldiers knocked her wand out of her hand. She was only able to escape by magically disguising … Continue reading

In the book, the Witch is about to kill Edmund right before he’s rescued, preventing the prophecy of the four thrones being fulfilled that way. It’s somewhat unfortunate that the movie doesn’t do this since it makes her dumber.[14]You could argue she was already dumb in the book for waiting as long as she did before trying to kill Edmund. In an earlier draft of the script, she planned to kill Edmund as soon as she could do so … Continue reading Anyway, the Witch brandishes a knife of her own and for a moment, it looks like she’s going to kill Ginarrbrik in anger. But she only cuts his bonds. “You’re not going to kill me?” he asks hopefully. “Not yet,” she says. Then she turns back to her general. “We have work to do.”

Next Week: Do the Pevensies Go Home or Stay and Fight? And Just What Work Does the Witch Have in Mind?

References

| ↑1 | In the book, Prince Caspian, a character says that “no one ever laughed at a centaur. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | As well he should be. In the book, Mrs. Beaver says, ““if there’s anyone who can appear before Aslan without their knees knocking, they’re either braver than most or else just silly.” |

| ↑3 | In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, a character who has been transformed into a dragon describes meeting Aslan thus. “I was terribly afraid of it… I could have knocked any lion out easily enough. But it wasn’t that kind of fear. I wasn’t afraid of it eating me, I was just afraid of it — if you can understand.” |

| ↑4 | Though even with that medium just saying that someone has an aura can be unconvincing by itself, especially if you lack C. S. Lewis’s eloquence. |

| ↑5 | I wouldn’t say it’s impossible for a movie. One I’ve written about on this very blog, The Prince of Egypt, kind of nails the numinous effect which Lewis gave Aslan in its burning bush scene. A kids’ fantasy movie of a similar vintage to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Nanny McPhee, does a great job making its title character come across as both “good and terrible at the same time.” Nanny McPhee arguably has some advantages over Aslan in that she dresses in black and actually does scary things when we first meet her. |

| ↑6 | In the book, the characters are in such awe of Aslan, that none of them dares be the first to address him and they get into a little argument over it. Including that might have helped the movie sell the “Aslan effect.” |

| ↑7 | He also emphasizes that in Narnia, unlike in our world, fancy clothes are actually comfortable. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? |

| ↑8 | I wish he said, “all I can,” since that’s closer to what he says in the book but that’s a nitpick. |

| ↑9 | I’m aware this wolf is called Vardan in the credits, but no one says his name in the film proper, so using it feels weird to me. |

| ↑10 | If you’d like my opinion on the controversy over the Narnia books’ portrayal of gender, here’s the shortest answer I can give. While Lewis did go on record as being antifeminist in other things he wrote, Narnia doesn’t relate to that much and half the accusations of misogyny it receives contradict the other half. Some say it’s misogynist because it portrays stereotypically feminine female characters positively and stereotypically masculine ones negatively. Others say it’s misogynist because it portrays stereotypically masculine female characters positively and stereotypically feminine ones negatively. (Many of the books’ young heroines could be described as either.) These two things can’t both be true, so half of the criticism must be wrong. |

| ↑11 | Well, it describes Peter and Susan as crying. Lucy isn’t the focus as much in this part of the book. |

| ↑12 | Though it should be noted that for all that Aslan’s words are jarring in their mundanity, keeping your sword clean is important as you don’t want it to rust. |

| ↑13 | In the book, as I mentioned, the Witch’s army hadn’t arrived yet and one of Aslan’s soldiers knocked her wand out of her hand. She was only able to escape by magically disguising herself as a boulder. While this is a memorable scene, I understand why the filmmakers omitted it since it amounted to randomly giving the Witch a new power and then not having her ever use it again. |

| ↑14 | You could argue she was already dumb in the book for waiting as long as she did before trying to kill Edmund. In an earlier draft of the script, she planned to kill Edmund as soon as she could do so on the Stone Table in keeping with tradition. In the book, she expresses regret over not being able to do that but decides that beggars can’t be choosers. |